By John Y. Brown III, on Sat Apr 5, 2014 at 10:30 AM ET

Note from John Y. Brown, III: Thanks to Randy Ratliff and Eric Crawford for drawing attention to about the best piece of journalism I’ve stumbled across in a long while. The piece, by Cory Collins, is a heartfelt and wrenchingly honest and humble personal piece asking probably the most unpopular question in central Kentucky this week on the eve of the NCAA Final Four; namely, Are we making too much of UK college basketball? Collins’ piece succeeds where so many pieces like it before have failed because it is not a disconnected and predictable scolding for misguided priorities but a sentimental and bittersweet journey of one thoughtful man who has been personally intertwined in the debate for many years and from many different vantage points. And who has reached a very thoughtful conclusion and desire to express it at precisely the moment when no one else in Kentucky really cares to hear it, including me. Which makes it all the more important that we do. And why I am glad I took the time to read it and respond to it just now.

(Photo by Jeff Gross/Getty Images)

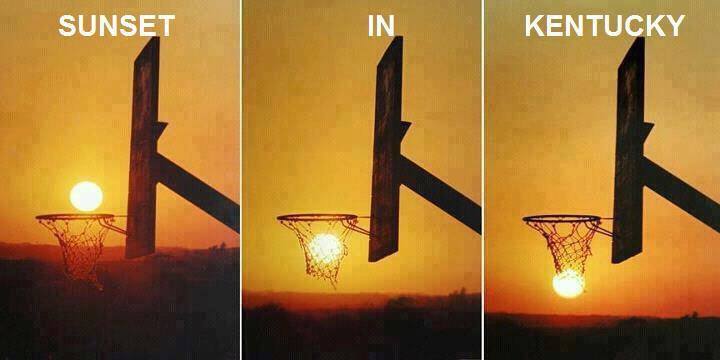

Allow me to bestow remembrance, lest you forget the Battle on Broadway, circa 2013.

I was sports editor of a publication you’ve undoubtedly encountered on newsstands, somewhere between USA Today and The New York Times on the rack. For the uneducated, unwashed masses, lest you forget my work, it was The Rambler, Transylvania University’s student newspaper, circulation: 1,000.

And there was a basketball game. A preseason exhibition. A storied crosstown Lexington rivalry that none of your kids will talk about: the Kentucky Wildcats hosting the Transylvania Pioneers, my Division III institution that stands just a short Conestoga ride down Broadway from the sacred walls of Rupp Arena.

As you might imagine, hype was high, even if trash talk proved difficult. Something about “Hey, UK! In the 1800s, you were our AG SCHOOL! And we reap what we sow!” didn’t exactly elicit fear in the hearts of seven-foot Wildcats.

We lost. I’ll spare you the bloody details. But Pioneers could take pride in a 30-second spot on ESPN’s SportsNation, where our own Brandon Rash (sort of) posterized Willie Cauley-Stein. The reaction was predictable, only lacking the low-hanging fruit that is a joke about Dracula.

The host, Colin Cowherd, mocked the name on the chest, as if to ask, where the hell is Transylvania?

It’s hard to blame him. For in the world of sports, we were Atlantis, lost in the Lexington, Ky., sea of blue.

Perhaps we wore crimson because we often acted as a vein pumping blood into the heart of Big Blue Nation. We had our fair share of duel-fandom, students who wanted Transy diplomas but UK basketball T-shirts. We had Matt Jones, who became the host of Kentucky Sports Radio. We have current senior Ben Lyvers, who helps lead a Pioneer cheering section but wore blue to the Battle on Broadway.

Perhaps we wore crimson because we often acted as a vein pumping blood into the heart of Big Blue Nation. We had our fair share of duel-fandom, students who wanted Transy diplomas but UK basketball T-shirts. We had Matt Jones, who became the host of Kentucky Sports Radio. We have current senior Ben Lyvers, who helps lead a Pioneer cheering section but wore blue to the Battle on Broadway.

And we had me. Stubborn, hipster me. Adamant that I had picked sides. Adamant that I had put my heart into Transylvania and a critical eye on Kentucky.

What I saw: it wasn’t that simple.

***

I don’t know when I became an outsider.

Before Cory Collins waxed poetic about the problems with big-money college athletics and referred to himself in the third person, Cory Collins played basketball on a plot of packed mud, a basketball hoop nailed to a tree. For hours, he played. And when the names taking the shots weren’t imaginary, they were often Wildcats.

I was just a rural Kentucky boy with a dream, and like many children, I loved things unconditionally and disproportionally. I loved shooting the basketball. And of all Wildcats, I loved Wayne Turner, and the way he shot free throws like he was mean enough to throw a baby backwards but kind enough to put a hand behind its head. I’d mimic the motion, because a swish is just as sweet when its origin makes no sense. And it made me smile. Why isn’t motivation always so simple?

I can’t pinpoint the exact moment that boyhood admiration for Big Blue disappeared. I turned into that typical creative, heady kid who seeks to assert himself. I dreamed beyond the boundaries of Kentucky, and thus, I cheated on my childhood and fell in love with new groups of young men playing ball games. I loved Texas’s baseball squad, UCLA’s color palette.

But these were fleeting fancies. In the end, I went to Transylvania, years after I discovered that a late-bloomer who has a way with words does not a scholarship athlete make. I thought my choice was made, my allegiance assigned. I’d left behind that Kentucky boy.

Instead, I found myself in an epicenter.

***

To live in Lexington with objective eyes is to see it: the big money program, the John Calipari car commercials, the burning couches, the fandom that does not border on obsession but defines it. I’ll admit that I was disenfranchised by its surround-sound persistence.

In 2012, when Big Blue raised its eighth banner, I was there as chaos hit State Street and Limestone. The success of selfless superstars like Anthony Davis and Michael Kidd-Gilchrist begat something much different — a mass self-indulgence. The destruction, the binge drinking, that’s what you’d see if you look no further than the six o’clock news.

So on the surface, it looked like everything that is wrong with the Kentucky fan base, what some may call the Alabama football following of the hardwood. A group that stands on a self-built pedestal, downgrades the outsider, and takes criticism as personal affront. But if that’s all you see, you miss a bit of beauty in Big Blue Nation:

You miss the fans that have nothing else to hold on to, not just in the streets of Lexington, but in the mountains, on the farms, inside the trailer parks where, without Big Blue, hope is a penny stock and they can’t afford it.

You miss the bond Big Blue perpetuates. As the aforementioned Mr. Lyvers explains it, “It just gives you chills. I’ve high-fived so many strangers in the past two weeks I had to ice my hand. It’s unifying.”

You miss the rare moment in the 21st century when something has the power to send people from their digital screens and screened-in porches to celebrate as a community.

But it should be said: if you only skim the surface of Kentucky basketball, you miss the dangers in the undertow.

***

When this culture surrounds you, so too does its flaws.

There are the obvious problems that you can find on the Twitter accounts of Jay Bilas of ESPN (@JayBilas) and Steve Berkowitz of USA Today (@ByBerkowitz) — Calipari’s unbelievable salary, the marketing of young men, an infrastructure so out of touch with its fan base that it sometimes feels like basketball’s McDonald’s, letting its poor indulge on unhealthy expectations until they are full.

But there are other things you see up close. There’s the way Kentucky basketball defines a city, despite a burgeoning culture of art, of inclusion, of creativity that fights to compete with its significance.

There is a dangerous dependence where identities, days, and moods are determined by wins and losses. It isn’t fandom, it’s a civil war, the difference between Kentucky being a national champion and a national punch line.

There appears to be a value system of athletics over academics, despite Calipari’s insistence to the contrary. UK is a team, in some eyes, before it’s a school. The school’s own official Twitter account, after 2012, led off its description promoting itself as the home of basketball’s best team. There was, surprisingly, no mention of its music program.

There is the onslaught of one-and-done, which has created a distance between fans and players. A veteran like Patrick Patterson is now the rarity. And while these fans understand better than many that dreams are fleeting, and that winning has a way of healing the hurt, they engage a coping mechanism. They decide the latest bunch will soon be gone, lament the loss of the old days and discard the new ones.

As an observer, as a liberal arts student and millennial hippie with cultural sensitivity and ingrained skepticism, this troubles me. But then I dare to look beneath the extremes. Beyond the ugly sides of fandom and into the beautiful in-between.

***

It was only two years ago when Kentucky represented the model for how youthful superstars could coalesce into something spectacular. It was only two months ago when Kentucky seemed to offer proof that no number of high school All-Americans could overcome the intangible necessities of experience and chemistry to succeed.

Now, the Wildcats are only two games away from potentially reclaiming the crown.

And on one hand, I dread it. I dread the fed beast that is the Big Blue Nation. I dread the calls to sports radio that will cement stereotypes of a Kentucky mindlessness that sees basketball, but misses the point.

But on the other hand, I can see it. I can already envision the sights of the state I called home. And some of it is beautiful.

I can see my Aunt Becky, as she battles cancer, for a moment able to stand strong, a tear in her eyes, a blue shirt over her heart, the words “our boys” on her lips as they dance across her television screen, victorious.

I can see the streets of Lexington, swarmed in jubilation. And beneath the binge-drinking, the danger, some student just happy to be there will hug a stranger, or take a selfie on Limestone Street with no intent to destroy, just to remember.

I can see a boy, somewhere, in the woods on a mud-packed court, running outside like I did in 1998, counting down imaginary seconds, perfecting Andrew Harrison’s follow through. Just a boy in the middle of nowhere that can dream of being somebody.

And yes, I can see the sight of freshman boys beneath confetti, a farewell party where their parting gift is the title, “National Champion,” smiling while we damn the system. The system that, God forbid, lets these boys of basketball leave to do what they love.

That’s when I’ll realize: who am I to damn the dreamers? Why should I, an outsider who can see the inside, fault the Big Blue Nation for its happiness?

I am critical. Of the money, of the culture, of the insensitivity and ignorance that can sometimes flow from a fan base so devoted to winning basketball games that it forgets that there are human beings beneath the jerseys, both the opposition’s and the one’s that spell “Kentucky” across the chest.

And there will be a time to revisit the one-and-done. To reconsider the explicability of recruiting players to use their university as a stepping stone to greatness, of sacrificing a sense of continuity for a sense of contention. To rediscover a game that used to be a Kentucky pastime before it became a Kentucky corporation.

But it is not just a cliché, in Kentucky, to miss the forest for the trees. So many problems dot the landscape that it’s easy to lose the scenery, to overlook the beauty.

I couldn’t truly see it until I left. I had intended to write about living within the city limits of Kentucky’s evil empire for four years, of lamenting how Kentucky ball courts became cult cathedrals.

But then I remembered that, beneath the burning couches, the hateful words on talk radio and the complicated racial relationship between player and fan (all of which still boils my Kentucky blood), there was happiness. There were smiles.

Because yes, we do have teeth in Kentucky. There’s just not always much reason to show them.

There’s a reason that a recent study from Gallup Healthways ranked two areas in the Commonwealth among the nation’s ten most miserable. For many, times are tough.

And if it takes millions of dollars, a basketball and a miracle run to bring those smiles back to Big Blue Nation — if it takes two Harrison twins and one coach with a car salesman’s smile — on some level, just maybe, it’s worth it.

Or maybe I’m still Wayne Turner in the wooded back yard, and I’ll never have a proper grip.