By John Y. Brown III, on Thu Aug 23, 2012 at 12:00 PM ET  The Twitterization of Higher Education The Twitterization of Higher Education

I’m excited for my son who is starting college this fall at one of the nation’s finest liberal arts institutions, Centre College.

I am a passionate believer in the value of a liberal arts education. I think a strong liberal arts education is the best foundation for vocational and civic preparation. Developing and honing thinking and communication skills is the foundation for success in most every job and will help ensure informed civic involvement. And, the liberal arts just makes for a richer inner life. Besides, what other form of education can both best prepare you for the technical tasks ahead and simultaneously help you convincingly rationalize why you are glad you failed if things don’t work out?

The liberal arts just make practical sense.

And I am grateful that our technically sophisticated world waited until a few thousand contemplative years had passed before we began communicating in Tweets, texts, IMing, and Facebook messaging, Imagine if the Platonic dialogues had been a series of cell phone texts between Socrates and Plato.

Or if Henry David Thoreau had Tweeted (and ReTweeted) his reflections at Walden in a series of 140 or fewer character insights instead of writing prose?

Imagine the Federalist Papers being hammered out by Jay, Madison and Hamilton in Facebook posts, comments, messages—complete with “Likes” and links to inspirational quotes and funny pictures. And of course with text acronyms (ROFLMAO, LOL, OMG WTF and the like).

It just wouldn’t be the same. It would still be an education, I suppose, but not convey much that inspires or enlightens. And it would produce a society of Dennis Leary’s– fast talking, sarcastic, misanthropic entertainers. We need Dennis Learys, no doubt about it. But not that many.

I suppose there is certainly irony in the fact that I am putting these thoughts in a Facebook post. Our modern social media is brilliant at forcing us to think quickly and condense richer thoughts into communicable fragments that are adequate to the task. Twitter, Facebook and texting allows instantaneous communication to a mind-bogglingly vast audience. And that provides incredible societal benefits.

Those benefits are primarily for data-driven communications. And that makes our world a safer, higher functioning and more efficient place. But the liberal arts and contemplative life makes our world a more interesting place— and allows us to create a more meaningful life.

I embrace both. Why? The Golden Mean, as the Greeks called it. The often desirable middle between two extremes.

And I learned that as part of a liberal arts education.

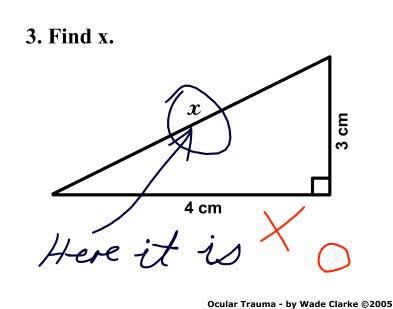

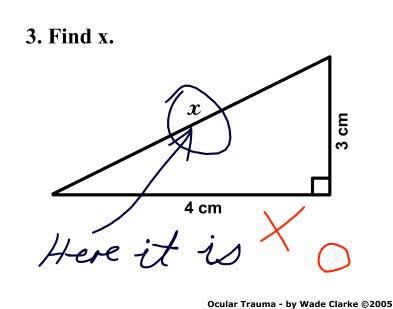

By John Y. Brown III, on Tue Jul 17, 2012 at 12:00 PM ET  Best wrong math answer ever? Best wrong math answer ever?

This gets my vote:

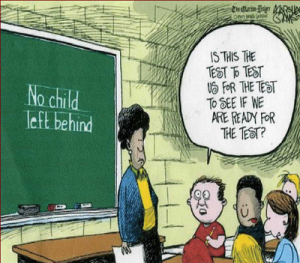

By Artur Davis, on Tue Jul 17, 2012 at 8:30 AM ET  Ed Kilgore’s latest posting in The New Republic is a pretty fair representation of how allegedly centrist Democrats have maneuvered their way into becoming skeptics of education reform, or at least reform more comprehensive than charter schools. Kilgore’s target is Governor Bobby Jindal’s statewide voucher initiative in Louisiana, and its embrace of a parental right to transfer children out of sub-standard districts. Kilgore focuses on what he describes as insufficiently strong standards to measure performance levels in private schools, or to weed out “bad apple” private academies that have no legitimate claim on public dollars. Ed Kilgore’s latest posting in The New Republic is a pretty fair representation of how allegedly centrist Democrats have maneuvered their way into becoming skeptics of education reform, or at least reform more comprehensive than charter schools. Kilgore’s target is Governor Bobby Jindal’s statewide voucher initiative in Louisiana, and its embrace of a parental right to transfer children out of sub-standard districts. Kilgore focuses on what he describes as insufficiently strong standards to measure performance levels in private schools, or to weed out “bad apple” private academies that have no legitimate claim on public dollars.

On one hand, Kilgore’s line of attack already seems slightly outdated: as he concedes, the state is actually in the process of developing metrics for evaluating which private schools are eligible for participation in the program, and the more pressing debate in Baton Rouge has not been over performance standards, but over which faith-based institutions are suitable for inclusion. Kilgore still persists in assuming that Louisiana’s voucher program will let in too many bottom-dwellers. But while lamenting the fact that an unidentified number (he unhelpfully describes it as a “lot”) of the schools applying for the voucher program suffer from curriculum flaws or other professional deficiencies, Kilgore offers no evidence beyond a reflexive suspicion of Louisiana’s competence that the weakest applicants will survive vetting. Of course, the larger inference, that too few of the state’s private schools provide a high quality alternative worthy of public support, requires a much rigorous assessment of comparative data like graduation rates, college enrollment, achievement based testing, etc.

Certainly, it’s a case that would also demand comparisons between private institutions and the existing state of Louisiana public schools. Kilgore spends literally no time analyzing the conditions in the state’s government run schools, and if he had, he would have uncovered appalling levels of mediocrity: according to the state’s education department, 44% of the state’s public schools received a D or F ranking under the state’s system for grading its K-12 institutions. Roughly one-third of graduating seniors are deemed to be inadequate in basic skills. Certainly, it’s a case that would also demand comparisons between private institutions and the existing state of Louisiana public schools. Kilgore spends literally no time analyzing the conditions in the state’s government run schools, and if he had, he would have uncovered appalling levels of mediocrity: according to the state’s education department, 44% of the state’s public schools received a D or F ranking under the state’s system for grading its K-12 institutions. Roughly one-third of graduating seniors are deemed to be inadequate in basic skills.

Nor does Kilgore grapple with a fact that even a private school skeptic must concede. At least some Louisiana private schools are high performers, but remain well out of financial reach for children whose median family income is one of the lowest in the country. Is it troubling to Kilgore that without vouchers, there is no consistently effective path for low-income Louisiana children to gain access to schools like New Orleans’ well regarded but 8% African American Isidore Newman, or the nationally recognized girls school at Mount Carmel Academy, with its 2% black population?

Read the rest of…

Artur Davis: Education Reform and its Centrist Critics

By Ronald J. Granieri, on Mon Jul 16, 2012 at 8:30 AM ET “It must be great being a college professor. You get summers off!”

All professors have probably heard this sentiment, in one form or another. It is usually accompanied by a sigh, the commenter wishing that she had such a cushy life. Though as many times as I have heard it, I know that it is not necessarily intended as a slight or a criticism. Most often, it is expressed as a good-natured if ignorant observation about the unusual perks of a somewhat exotic job, rather like when people tell flight attendants, “Wow, you get to fly all over the place for free!” All professors have probably heard this sentiment, in one form or another. It is usually accompanied by a sigh, the commenter wishing that she had such a cushy life. Though as many times as I have heard it, I know that it is not necessarily intended as a slight or a criticism. Most often, it is expressed as a good-natured if ignorant observation about the unusual perks of a somewhat exotic job, rather like when people tell flight attendants, “Wow, you get to fly all over the place for free!”

What makes academic life seem so exotic is that being a professor is more like practicing a medieval craft than pursuing a modern profession. As befits a world of robes, elaborate ceremonies, and gothic quadrangles, universities maintain a system of unique rewards and demands that harkens back to pre-modern times.

Practically, this means that the work habits of academics are hard to reconcile with the patterns of most normal professions. Academics are supposed to do two things—produce knowledge and share that knowledge with the larger community. They are also, according to tradition, supposed to govern and police themselves. Although that does not mean what it used to, when universities had special laws and even their own jails (some of which are preserved as tourist sites in European university towns such as Heidelberg in Germany) it still means that universities pride themselves on being governed by their own—deans, directors, chairs, and presidents drawn from the faculty.[1]

In present parlance, that means university faculty members are evaluated according to the classic trilogy of research, teaching, and service to the academic community.[2]

Here we get at the root of the contrast between what people think professors do and what they actually do. For the things that are most visible to the outside world—teaching in the classroom, meeting with students in office hours, grading assignments—is also only a part of what academics are expected to do. When junior faculty sigh and say they “really need to find time to do my own work,” they are rarely referring to teaching. Indeed, even the most dedicated teacher who devotes time to developing and preparing new courses is going to need a lot of time alone to gather and develop new knowledge. That means everything from reading and reviewing the newest literature in their field to working on their own projects. None of these tasks lend themselves to punching a clock. Academics are paid to think and read and write, which means a lot of their time is unstructured, and they have freedom to organize it according to their own priorities. That is the positive view. The less positive view is to note that unstructured work means that it is never really over. There is always more to read, and those books and articles don’t write themselves.

So academics have to deal with less immediate but more constant pressures than people in other professions, all the year round. That is not a complaint, since I am sure that a lot of people in other types of jobs wish the pressures they felt were less tangible, but it is something to think about before claiming that because professors only teach a few classes a semester, or do not teach in the summer, they have a lot of “free time.” So academics have to deal with less immediate but more constant pressures than people in other professions, all the year round. That is not a complaint, since I am sure that a lot of people in other types of jobs wish the pressures they felt were less tangible, but it is something to think about before claiming that because professors only teach a few classes a semester, or do not teach in the summer, they have a lot of “free time.”

If those outside academe have a hard time understanding what goes on there, that is also because the practical details of academic life can vary greatly depending on both the type of university or college and the field in which an academic operates (and of course upon whether one is on the tenure track). Schools can range from teaching-heavy colleges (which would include both small private institutions and satellite campuses of state universities, as well as community colleges) where the average professor is expected to offer four or five courses a semester (and do all of her own grading) to the elite research universities where the load is usually two courses a semester—perhaps less, if the faculty member has special administrative responsibilities such as chairing a department or directing an institute—and where most of the grading is done by graduate students, as part of their apprenticeship before beginning their own academic careers.[3]

Teaching and research exist in tight, inverse proportions: the lower the teaching load, the higher the research expectations.[4] What those research expectations may be depends on the field. In the natural sciences, successful academics are expected to manage a laboratory and conduct a range of experiments. That means hiring and supervising a small army of student assistants, and applying for and managing the large outside grants necessary to fund the operations. Natural scientists also publish several research reports and articles a year. Most of those publications will be multi-authored, which (to put it most charitably) allows scientists to leverage their work into more publications than they could have produced on their own. Humanities and social science professors publish fewer and longer pieces—journal articles and books, usually single-authored—and are less dependent on labs and grants, except when they need to travel to archives.

Critics ranging from undergraduates unable to get an appointment to complain about midterm grades to Wall Street Journal op-ed writers have attacked the attention faculty pay to what can appear to be unnecessarily esoteric research.[5] Imust admit to having mixed emotions about these criticisms. There is nothing wrong with demanding that faculty remember their responsibility to share their knowledge with non-specialists, and I am a firm believer in the importance of teaching. What such critics tend to miss, however, is the responsibility of professors not only to repeat old knowledge but to create new knowledge as well. At their best, such criticisms can serve to puncture the pomposity of over-specialized academics. At their worst, they sink to the level of the know-nothings who want to eliminate the library budget because no one has read all the books that are already in it.

Read the rest of…

Ronald J. Granieri: A Glimpse Behind the Ivy Curtain

By John Y. Brown III, on Fri Jul 6, 2012 at 12:00 PM ET  Maybe we should have “Thank an English Teacher Day.” Maybe we should have “Thank an English Teacher Day.”

English teachers have had a greater impact on my daily interactions and thought processes than teachers from any other subject matter.

Even quips and famous quotes have stayed with me longer than, say, the quadratic formula or parts of the periodic table.

“Poetry is an overflowing of emotion….reflected in tranquility”

William Wordsworth

Taught to me by my Bellarmine College English professor, Wade Hall, in 1985. Among much, much more that also is still with me after all these years.

Thank you, professor Hall. And I mean that sincerely. Not just because “I know which side of my bread the butter is on.” A phrase you used to describe me during our first classroom interaction.

By Jeff Smith, on Wed Jul 4, 2012 at 1:30 PM ET This article explains the legislative process better than any polisci textbook I’ve ever used in class. [Charlotte Observer]

By Jonathan Miller, on Tue Jul 3, 2012 at 8:30 AM ET Writes Roger Waters in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette:

On Tuesday, I will be visiting Pittsburgh to perform my Pink Floyd hit “The Wall” at Consol Energy Center. By coincidence, the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (USA) has gathered this week in Pittsburgh.

One issue the Presbyterians will be debating is whether to take action in support of Palestinians living under Israeli occupation in the West Bank, under siege in Gaza and as second-class citizens in Israel under the rule of the apartheid government there.

I write in support of those Presbyterians who would like their church to divest its holdings in three U.S. companies — Motorola Solutions, Hewlett-Packard and Caterpillar. These companies profit directly from Israel’s illegal occupation of the West Bank and suppression of the Palestinian people in both the West Bank and Israel itself.

While there are very legitimate issues with the Israeli government’s handling of the West Bank’s disputed territories (I support the transfer of most of these lands to a new Palestinian state), the notion that Gaza is under siege by Israel (when Hamas just fired 150 rockets last week into civilian Israeli territory), or that Palestinians who live in Israel proper are second-class citizens under an apartheid regime (when they share every single right and responsibility of citizenship as their Jewish neighbors), cannot be classified as anything but malicious lies.

The decision to divest is an independent issue, and while I am strongly opposed for the reasons I outline here, reasonable minds certainly can differ. But if people base the decision on Waters’ lies, they are doing a great disservice to the dialogue.

The answer? We do need education. Indeed someone just wrote a good book on the subject…

By Artur Davis, on Thu May 31, 2012 at 8:30 AM ET  Mitt Romney’s venture into education policy this week was overdue, but bold in the right places. It was a striking improvement from his previous blend of clichés about local control and hints that the Education Department might be eliminated altogether. Mitt Romney’s venture into education policy this week was overdue, but bold in the right places. It was a striking improvement from his previous blend of clichés about local control and hints that the Education Department might be eliminated altogether.

The conventional wisdom is that the Obama Administration has all but swept education reform off the table with its own maneuvering toward the center on the issue. The reality, though, is that the White House has mixed instances of toughness—incentivizing states to embrace charter schools, defending mass firings of teachers in underperforming Rhode Island districts—with a conventional Democratic resistance to merit based pay, vouchers, or any revamping of state tenure laws. It is a record that has won bipartisan plaudits from reformers, but not one that has made much headway in alleviating the festering mediocrity that marks many of our public schools, and that careens into outright disgrace in most inner city venues.

In fact, success under the Obama model would look remarkably similar to the landscape that prevails in education today: a scattering of high profile innovations in either deep pocketed big cities, or states that already have a strong reform culture, with the prospects of individual children turning largely on the vagaries of location and local leadership. Not surprisingly, the politically influential teachers unions have grumbled about the current agenda, but they have adjusted to it as an incremental set of half measures that they can fend off state by state. In fact, success under the Obama model would look remarkably similar to the landscape that prevails in education today: a scattering of high profile innovations in either deep pocketed big cities, or states that already have a strong reform culture, with the prospects of individual children turning largely on the vagaries of location and local leadership. Not surprisingly, the politically influential teachers unions have grumbled about the current agenda, but they have adjusted to it as an incremental set of half measures that they can fend off state by state.

Read the rest of…

Artur Davis: Romney’s Education Gambit

By Artur Davis, on Tue May 22, 2012 at 1:30 PM ET  Last week, The Chronicle of Higher Education waded headfirst into the culture wars by terminating one of its bloggers for a column excoriating the black studies discipline and calling for its end. The saga around Naomi Schaeffer Riley has ignited a predictable back-and-forth, from the partly organic, partly organized attack by the left on the original piece, to conservative bloggers who have defended her against political correctness run amuck. Last week, The Chronicle of Higher Education waded headfirst into the culture wars by terminating one of its bloggers for a column excoriating the black studies discipline and calling for its end. The saga around Naomi Schaeffer Riley has ignited a predictable back-and-forth, from the partly organic, partly organized attack by the left on the original piece, to conservative bloggers who have defended her against political correctness run amuck.

I’m of two minds about the controversy. Most of the assault against Riley does seem like shop-worn viewpoint censorship. As even a liberal critic like Eric Alterman has pointed out, labeling the essay as “hate speech” is a frivolous, overwrought charge, and Alterman is right to recognize that a formal response by the black studies faculty at Northwestern which alludes to past discrimination against black college applicants seemed simultaneously pointless and defensive about the capacities of some of the department’s students—who, of course, are not even all black.

But the Riley essay does not strike me as the best line of defense for admirers of intellectual candor. It is not exactly an exercise in rhetorical grace: there is a talk-radio style bluntness to its 500 odd words that is dependent on name-calling: “left wing victimization claptrap”, “liberal hackery”, a parting shot that practitioners of black studies should defer to “legitimate scholars”. Substantively, the essay’s thesis, that a Chronicle article exposed an intellectual sloppiness in the black studies field, is overly reliant on examples from three dissertations to make a vastly more far-reaching point. Even if two of the papers seem hopelessly polemical and one of them sounds hopelessly opaque, it’s a stretch to indict an entire discipline on such a thin foundation. The whole thing feels like an impressionistic hit dashed off to meet a deadline. But the Riley essay does not strike me as the best line of defense for admirers of intellectual candor. It is not exactly an exercise in rhetorical grace: there is a talk-radio style bluntness to its 500 odd words that is dependent on name-calling: “left wing victimization claptrap”, “liberal hackery”, a parting shot that practitioners of black studies should defer to “legitimate scholars”. Substantively, the essay’s thesis, that a Chronicle article exposed an intellectual sloppiness in the black studies field, is overly reliant on examples from three dissertations to make a vastly more far-reaching point. Even if two of the papers seem hopelessly polemical and one of them sounds hopelessly opaque, it’s a stretch to indict an entire discipline on such a thin foundation. The whole thing feels like an impressionistic hit dashed off to meet a deadline.

Read the rest of…

Artur Davis: The Blogger and Black Studies

By Artur Davis, on Fri May 18, 2012 at 10:00 AM ET Who knew that Massachusetts provides an opportunity to add a touch of color to the almost all white US Senate?

Who knew that when Democratic candidate Elizabeth Warren tailored her professional biography to cultivate ties with people who are “like I am”, she had in mind not left-leaning academics, or advanced degreed professional women, or bankruptcy policy wonks, but Oklahoma Cherokees? There is a rich vein in humor in the Boston Herald’s revelation that Harvard Law School touted the clearly Caucasian Warren as a Native America and that for nine years, Warren listed her ancestry in the same manner in official law school directories.

To be sure, the Warren campaign handled the damage control front with a skilled deflection: Team Warren has professed much outrage over any insinuation that her climb up the academic ladder was lifted by affirmative action (a claim her Republican opponent, incumbent Senator Scott Brown, has not remotely raised) and the New Republic has equated the whole thing with far-right birtherism regarding Barack Obama’s background. It’s a clever dodge that minimizes Warren’s creative accounting of her ancestry while reviving the liberal meme that Republicans have a beef with achievements that don’t belong to white men.

Here’s one hope that Warren doesn’t get away so easily. For all the mirth that has greeted the disclosures, there is a serious thicket of questions here for the professor and an embarrassing glimpse into the East Coast elite liberalism that she represents. One appropriate line of inquiry is whether Warren’s drive to reestablish her Cherokee roots manifested itself in any more tangible outreach to Native Americans in, say, her home-state of Oklahoma, who may not have perused law school association guides. The marginalized young adults in that community would certainly have relished a connected, powerful role model, and it is fair game to press Warren on whether the ethnic pride she described last week ever led her to be that person. And it is equally legitimate to ask whether Warren ever used the Native American identification in any context other than a directory that would have been a primary resource for law school recruiters and head-hunters.

Read the rest of…

Artur Davis: Elizabeth Warren, Minority Crusader?

|

The Recovering Politician Bookstore

|

The Twitterization of Higher Education

The Twitterization of Higher Education