By John Y. Brown III, on Tue Aug 26, 2014 at 12:00 PM ET  Smiling for pictures. A confession. Smiling for pictures. A confession.

My new family Facebook photo got me to thinking about something that has always been a little understood pet peeve of mine: Smiling for pictures.

The kind waiter at the restaurant offered to take a picture of us tonight and we stood together and posed along the street behind us. His fist shot caused him to hesitate and give me a look that said, “C’mon guy. What’s wrong? Smile for goodness sake.” So I tried harder for his second attempt and only modestly succeeded, as you can see. It’s not really a smile but more of a pose that tries to appear as a candid shot yet could be honestly mistaken by others for a smile. Like when you aren’t sure of a person’s name and when introducing them you slur what you think is their first and last name into an almost indecipherable gibberish name that you hope sounds close enough to fool everyone involved.

And that is about the best I ever seem able to do in photos. (Note; the other profile pic of me with just my wife is an exception and I believe I was honestly laughing about something when it was taken…so it really wasn’t a successful “posed smile.”)

And the “posed smile” is the problem for me. I don’t remember when it started but as far back as I can remember I never liked posing for pictures. As a boy it was because I was–like most all boys–too restless to stand still for 6 to 7 consecutive seconds. And to be expected to smile on top of this inconvenience was simply asking too much.

Later on as a young man, I still disliked standing still but mostly didn’t smile fully because I was, in my own petty way, rebelling against whoever was demanding the picture. Sure, on the surface I may be posing for the picture. But I wanted to be clear I wasn’t anyone’s monkey and the childish rebel in me was getting a subtle satisfaction by not smiling fully for the requested picture.

And then there was the period between being a young adult and a full adult when I was in college and law school where I did pose for pictures when requested but refused to smile easily because I wanted to look smart and serious and deep (I was for a while a philosophy major and wanted to look the part) —and also not be a poser who would lower himself to manufacturing an emotion to create a fake image for others to see. In other words, I feared being a phony, maaan!

But then as an adult, no longer as restless and seeing the benefit of taking photographs with family and friends, I tried to smile but couldn’t pull it off. I don’t know if it was that I never learned when I was younger how to just smile and “say cheese” when someone was taking a picture or if there is just something in me that can’t beam happiness on cue.

Maybe there is just this odd combination of restlessness, rebellion and philosophical determination “not to give in to ‘the man'” by smiling naturally for photos. Or maybe you can’t teach an old dog a new trick. But whatever the reason, there is a “smile deficit” I suffer from in most photographs I am in. I typically look to be the least happy person in the photo. Not because I really am. I like to think my happiness is at least in the 50th percentile of people with whom I am photographed. I’m just not very good at expressing “photograph happiness.”

And my hope is that “photograph happiness” is a lot like other kinds of happiness. It’s not something that is easily seen from the outside as it is something you feel on the inside. So if you see a picture of me that I post and I appear to be in mid-scowl, just try to overlook the clueless non-pose and just know I’m probably smiling –or trying to smile–on the inside.

By John Y. Brown III, on Tue Aug 19, 2014 at 12:00 PM ET

By Saul Kaplan, on Mon Aug 18, 2014 at 8:30 AM ET  I would like to go to the new $1.2 billion Cowboys Stadium in Texas to watch the movie The Matrix. I have no interest in watching a football game there. Full disclosure, I have never liked the Dallas Cowboys. I think it has something to do with a mean cousin who loved them and harassed me about it in grade school. I would like to go to the new $1.2 billion Cowboys Stadium in Texas to watch the movie The Matrix. I have no interest in watching a football game there. Full disclosure, I have never liked the Dallas Cowboys. I think it has something to do with a mean cousin who loved them and harassed me about it in grade school.

In a classic egomaniacal move Cowboy’s owner Jerry Jones ordered a ginormous jumbotron that hangs 90 ft above the playing field spanning from one twenty yard line to the other, right in the likely flight path of many punts.

How big is this oversized HDTV? Its display screens are 159 by 72 feet and it weighs 432 tons. Talk about surround sound.

And talk about a design flaw. Their user experience expert must have been so focused on delivering an incredible experience for the fans attending the game that they completely forgot that the stadium was going to host actual football games.

How big a design error is this? You judge.

Christopher Moore, an Assistant Professor of Physics at Longwood University in Farmville, VA, blogged about the physics of punting on ilovephysics.com:

” A study in 1985 of 238 punts made by 24 different NFL punters found that punters typically don’t punt for maximum distance, but to balance distance with hang time. The study found that on average, NFL punters kick the ball at an angle of 57 degrees with an average speed of 60 mph. With these parameters, a NFL punt would have an average height of about 90 feet, which is exactly the height off the ground of the Cowboy’s scoreboard. Air resistance would probably decrease this number 10-15%, though. More important, though, were parameters for “elite” kicks. An elite kicker can boot the ball with speeds up to 70 mph. At the same average angle, that results in a height over 120 feet.”

The physics of kicking a football suggest that the jumbotron will be hit a lot. This is a huge design screw up and Jerry Jones should be forced to move the HDTV screen into his home where I am sure it would easily fit without getting in the way.

But no, this is the NFL where team owners rule the roost. Jerry Jones petitioned (probably more like told) NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell that a new rule would have to be created to accommodate punts that will inevitably hit the video screen. And it was done. The NFL announced the following new rule:

“If a ball in play strikes a video board, guide wire, sky cam or any other object, the ball will be dead immediately, and the down will be replayed at the previous spot”

That the rule will come into play is no longer hypothetical. In the third quarter of the first exhibition game played in the new venue between the Cowboys and the Titans, the backup punter for Tennessee, A.J. Trapasso, hit the jumbotron squarely and the ball bounced straight down. The punt was ruled dead and the down replayed.

During warm-ups before the game Trapasso had hit the screen monstrosity three times and the Titan’s starting punter, Craig Hentrich had nailed it a dozen times.

You would think they could have figured this out during the design process. There is no room for ego in good design and I still don’t like the Dallas Cowboys.

By John Y. Brown III, on Mon Aug 11, 2014 at 12:00 PM ET

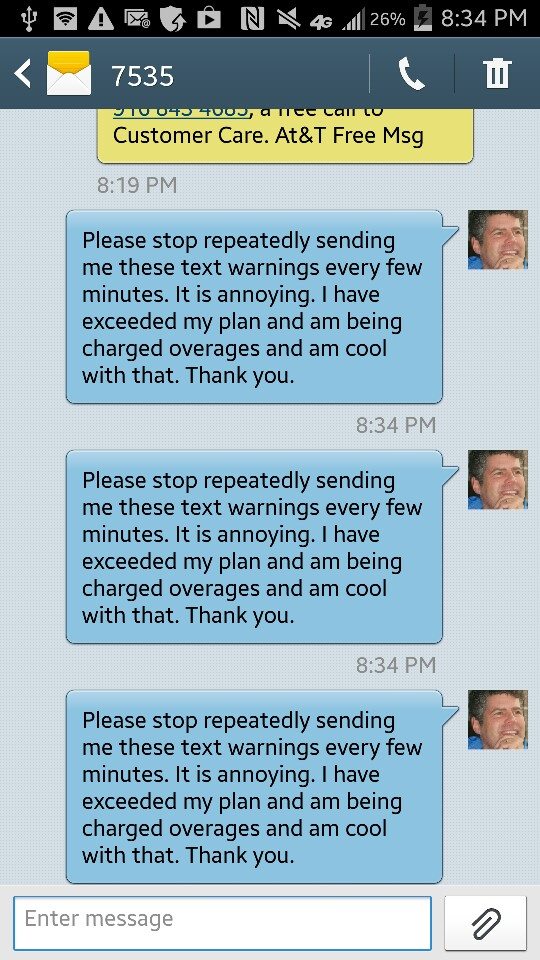

My cell phone –an ATT Android–has a visual voicemail feature that tells me when I have a new voice mail message.

But wait, there’s more.

The visual voicemail app also, with some voicemails, will delay the notification for several hours. Or even a day.

I know what you are thinking. It must not work right. But I figured out what really must be going on.

This feature, I have to assume, somehow measures the enthusiam of the caller and will delay notifying me of the call accordingly –to the extent the person doesn’t seem eager to talk to me.

I mean, what else could it be? Right? There’s no other reason I can think of for the voicemail to work this way.

Dang. Technology sure is amazing.

Oh, so yeah. When you leave me a voicemail be sure you sound enthusiastic so I will get it right away.

By Saul Kaplan, on Mon Aug 11, 2014 at 8:30 AM ET  Irwin Kula is an eighth-generation rabbi known for his fearless attitude about change — a rare quality among religious leaders who tend to adhere closely to tradition. Irwin Kula is an eighth-generation rabbi known for his fearless attitude about change — a rare quality among religious leaders who tend to adhere closely to tradition.

Kula, president of the National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership (CLAL) in New York and the author of Yearnings: Embracing the Sacred Messiness of Life, has dedicated himself to opening up the wisdom of his 3,500-year-old faith to be in conversation with the world.

Kula preaches the “highest possible institutional barriers between church and state,” with the “lowest possible communication barriers.” He welcomes intermarriage and interfaith dialogue. He recognizes God not as a “Seeing Eye,” but in “experiences of love, caring, and connection.”

Many consider Kula progressive; others, disruptive. But Kula maintains that institutionalized disruption is essential to adaptation and growth.

Rabbi Kula looks like the wise man of children’s books. He has a handsome widow’s peak, and speaks with homiletic pauses and animated hands. When asked about how his beliefs developed, he answers in stories.

At 14, Kula was thrown out of the private parochial school he attended for challenging the Torah. “I would ask a class of 25 students questions which were probably a touch ‘teenagerish’,” he recalls. “I’d ask, ‘You don’t really believe this — God splitting seas? Come on, this is not what this is actually saying’.”

This rebellious streak would come to define his practice.

The problem with most religious leadership, Kula claims, is that its mission is to convert the non-affiliated. “Religion is not about creed, dogma, or tribe,” he counters. “We need to stop judging our success by membership dues — this isn’t about how many hits. First and foremost, religion is a toolbox designed to help human beings flourish.”

Kula claims that he finds himself often at odds with the concept of “God” as commonly invoked in the American public arena. To him, this is the God of touchdowns and wars, an intervening God who “casts out” unless one “buys in.” “No religious or political system has a hold on being moral,” Kula says. “Systems are only as good as their people.”

For most of his rabbinic appointment, Kula kept these views to himself. Only after the September 11 attacks did he begin to more openly preach what he himself practiced.

“I was very unnerved, knowing the religious impulse compelled that,” Kula says. After the tragedy, he shut down his teaching for three months to reevaluate his role as a spiritual leader. When he returned to the synagogue, he had made the decision “never to teach Judaism again simply to affirm the group’s identity.”

In 2013, Irwin Kula recounted the narrative of his spiritual conversion to a packed theatre of global business leaders at the Collaborative Innovation Summit, an event hosted annually by the nonprofit Business Innovation Factory (BIF) in Providence, RI. On stage, the rabbi made an ambitious appeal to his audience, whom he knew to be composed of astute tinkerers and serial entrepreneurs: He asked them to join him in his mission to innovate religion.

Kula is a fervent believer in accessing insight beyond the religious tradition. “It’s really important to speak to non-incumbents,” he maintains. “The less you speak exclusively to your own ‘users,’ the better shot you have of keeping your own practices from becoming incredibly distorted.” His CLAL runs a program called Rabbis Without Borders, dedicated to fostering open dialogue across cultural and religious barriers.

Stories of innovation often feature “two kids in a garage.” Kula’s goal has been to tell an innovation story from the cathedral. “Religion’s just a technology,” his BIF talk began. “How the hardware of humanity gets used will depend on the software.”

His talk covered how the rapid advancements of the digital infrastructure age demand that we broaden our ethical horizons: What are the new crimes? In this new order, who is included and what are their rights? As we redefine morality, the need to innovate faith becomes especially pressing.

“The most interesting businesses ask ‘impact on society’ questions, which are more complex than ‘killer app success’ questions,” Kula reflects in hindsight. “At BIF, I asked, ‘What would happen if we applied innovation theory to religion, to compress the resources it takes to create good people?’”

Kula looks forward to returning for BIF10 in September.

“If a homily is 15 minutes in church, it’s 18 minutes at BIF,” he says. “As conferences go, BIF embodies total equality between the storytellers and their audience. In many ways, it’s the best of what a spiritual community is — we’ve got to bottle that.”

This is the second of a 10-article series of conversations published on the Time website, authored by myself and Nicha Ratana, with transformational leaders who will be storytellers at the BIF10 Collaborative Innovation Summit in Providence, RI, on Sept. 17-18.

By Saul Kaplan, on Mon Aug 4, 2014 at 8:30 AM ET  John Hagel speaks with satisfying precision. He has kind eyes and stern glasses, which together dominate the screen during a Sunday-afternoon Skype conversation. John Hagel speaks with satisfying precision. He has kind eyes and stern glasses, which together dominate the screen during a Sunday-afternoon Skype conversation.

As co-chairman of Deloitte’s Center for the Edge, Hagel hunts for unexploited capability on the “edges” of business and makes the case to include them on the CEO’s agenda. “The edges are most fertile areas for innovation,” he says. They are an important place to watch, because what happens at the edges transforms the core.

Hagel’s research encompasses geographic edges (overseas economies), demographic edges (younger generations entering the workforce, their unmet needs), and the edges of technological discovery. If there’s anything his work has taught him, it’s that the manual is less of an asset than the “ability to respond to unexpected events.”

Hagel believes that we are approaching fundamental revaluation of the role corporations play in our lives.

Corporations in the first half of the 20th century were built around what Hagel calls the “push” business model. The greatest asset of these vertically integrated, gargantuan structures was their knowledge stock — aggressively protected trade facts and formulas that allowed them to forecast with reasonable accuracy which direction to “push” operations.

However, this push model is failing in the face of expanding digital technology infrastructures, Hagel claims. Reinforced by long-term policy shifts toward economic liberalization, barriers to market entry have been significantly reduced on a global scale. The pace of our transactions has increased, the lifespan of knowledge stocks has decreased and competitive intensity in the US economy has doubled in the last 40 years. Hagel calls this “the dark side of technology” — a counter-narrative to the Silicon Valley script of dazzling possibility.

But Hagel sees an antidote to this volatility: openness. “People are realizing that they need to collaborate to survive,” he says, “You have to give up your secrets, your competitive advantage. It’s the only sustainable edge.” Hagel calls this new order the world of “pull,” and he describes it in his book, The Power of Pull: How Small Moves, Smartly Made, Can Set Big Things in Motion.

“Pull,” a splendidly iconoclastic antidote to traditional American corporate culture, means moving away from hub-and-spoke networks where knowledge was selfishly guarded to mesh networks that favor collaboration. Pull rejects claims to have all the right answers and instead favors asking smart questions.

“When people come at you with a façade as if everything’s under control, it does not generate trust,” Hagel says. “Admitting you don’t know something is a prerequisite to making progress.”

Rather than showing strength, influence in an uncertain economy paradoxically comes from expressing vulnerability. Yet Hagel says he had to learn the value of vulnerability. As a boy, he was often subject to his mother’s hostile temper.

“The key lesson that I took from my childhood was that my needs did not matter,” he explains. Upon his entry into management consulting, Hagel readily embraced the maxim that the client’s needs had to come first. “For the first part of my career, I was a servant of others,” he says. “The idea that others could help me was completely foreign to me.”

Hagel attributes the shift in his thinking to a talk he gave at the Collaborative Innovation Summit hosted annually by the nonprofit Business Innovation Factory (BIF) in Providence, RI.

“Saul Kaplan invited me to be a storyteller at BIF6, and I’ve talked a lot and in various conferences and settings, and that seemed perfectly fine,” Hagel says. “But then he said, ‘We want you to talk about a personal experience and what you’ve learned from it,’ — and that was very scary.”

“Stories are not my thing. I am a person of reason and analysis,” began Hagel’s BIF6 story. But sure enough, he shared two tales of formative childhood experiences in a passionate expression of his business philosophy that later became the story of that year’s Summit. “It was the first time I ever got on stage and talked about myself,” he reflected in hindsight.

The experience was an incredible catalyst. “It really unleashed a tremendous sense of potential and possibility, that by sharing my personal experiences, by talking about things I didn’t know, and I connected with people in a way that I would never have had I just given my standard speech. I can’t wait to be a storyteller at BIF10 in September.”

“The key lesson I got from the BIF Collaborative Innovation Summit,” Hagel says, “is that innovation is ultimately not about ideas, it is about personal connection.”

This is the first of a 10-article series originally published on the Time website, authored by myself and Nicha Ratana, of conversations with transformational leaders who will be storytellers at the BIF10 Collaborative Innovation Summit in Providence, RI, on Sept. 17-18.

By John Y. Brown III, on Thu Jul 24, 2014 at 12:00 PM ET  Losing it! Losing it!

After receiving 3 calls in less than 5 minutes from a telemarketing company—and all 3 interrupting an important business call– I decided to retaliate.

I called back the number and got an answer from a robotic telemarketing sales rep and I said, “Hello. How are you doing today? I’m interrupting your day to try to sell you some s**t you don’t need. Do you have a few minutes to talknow?”

And then I gave the real reason I was calling and asked that my number be removed from their call list.

But he hung up on me.

Cold call sales is just hard like that.

(Note: Forgive me. I try never, ever to lose my cool and mostly succeed. But this wasn’t one of those times. But I’m all better now. And even feel a little guilty. But only a very little.)

===

Disconnect?

Is it possible to receive a monthly phone bill from your phone carrier so detailed with information that it takes 8 full pages to report it all, but nowhere on this detailed bill is there a single reference to a phone number for your carrier if you have any questions?

Yes, it is.

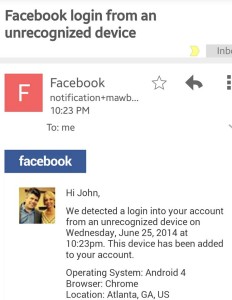

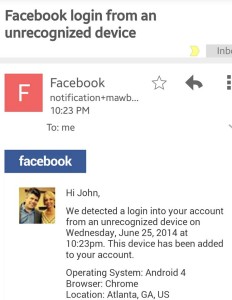

By John Y. Brown III, on Tue Jul 8, 2014 at 12:00 PM ET  Whoa, Dude! Whoa, Dude!

John’s excellent adventure–at least according to Facebook

Last night I was in Lexington and did login to Facebook account with a new replacement phone.

But this morning when I woke up and read the notice, it says I was in Atlanta, GA!

I have no recollection of driving to Atlanta last night to log into Facebook but apparently, according to Facebook, I did. I do remember the drive back to Louisville seemed a little longer than usual. I have no recollection of driving to Atlanta last night to log into Facebook but apparently, according to Facebook, I did. I do remember the drive back to Louisville seemed a little longer than usual.

All I know is I woke up this morning with a hazy memory of last night. I just hope it was awesome.

By John Y. Brown III, on Fri Jun 20, 2014 at 12:00 PM ET  The upside of Dirt Devil shopping. The upside of Dirt Devil shopping.

It shouldn’t be this hard to buy a Dirt Devil to vacuum out blueberry muffin crumbs in my car floorboard.

I have tried Office Depot, Stienmart, Best Buy, Staples, and a couple of others and empty handed.

It was very frustrating.

But just a few minutes ago I took a Dirt Devil shopping break at Heine Bros and got a Rooibee Red Tea and am listening to the Black Crowes.

And now I really don’t mind at all that finding a Dirt Devil is so difficult. In fact, as I am listening to the live version of Can’t You Hear Me Knocking, I’m actually glad it is so difficult because it led me here.

So if you have been shopping all afternoon for a Dirt Devil and are frustrated, hang in there. It does get better when you eventually end up at Heine Bros. You won’t find a Dirt Devil, but you do get to enjoy a Rooibee Red Tea and get to listen to the Black Crowes.

And as you head home, you’ll probably decide it’s easier to just stop eating blueberry muffins. At least in your car.

And think to yourself, “It’s all good.”

===

Dirt Devils have apparently been replaced by Magic Dusters.

The name “Magic Duster” sounds better and is slightly less occultish sounding for a household clearning device than “Dirt Devil.”

But they really aren’t all that magical, if you ask me. Of course, your threshold for defining “magical” may be lower than mine–but I’m not seeing it.

Put it this way, it’s not as magical as something that is battery operated. Or more to the point, the Magic Duster is less magical, powerwise, than blueberry muffin crumbs. Put it this way, it’s not as magical as something that is battery operated. Or more to the point, the Magic Duster is less magical, powerwise, than blueberry muffin crumbs.

By John Y. Brown III, on Thu Apr 24, 2014 at 12:00 PM ET Is it me or do ATM’s seem more talkative than they used to be?

It used to be you’d slide in your card and enter the amount you wanted and out the money would come.

Nowadays, though, ATM’s seem emotionally needy and ask endless and unnecessary questions–about my balance, my different accounts, service charges, and my judgement (“are you sure you want this amount?”) and on and on.

It’s as if they are lonely and just want some sort of interaction with anybody or anything.

I am waiting for them to ask me if I saw the game Thursday or ask me where I am headed next– or maybe try to guess what the money is for. “Is it bigger than a bread basket? If so, press 1”

I feel sorry for them but I just don’t have time to nurture these machines. I feel sorry for them but I just don’t have time to nurture these machines.

Maybe someone can let them have one day off a.week to socialize with other ATM’s so they can get their emotional needs met–and then when they deal with me just give me my money instead of playing 20 Questions.

|

The Recovering Politician Bookstore

|

Smiling for pictures. A confession.

Smiling for pictures. A confession.