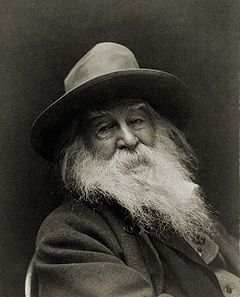

A few weeks ago, I was reading Walt Whitman, enthralled by the energy and rhythm of his poetry. It’s easy to see why he was embroiled in fights with 19th-century censors. “I will go to the bank by the wood and become undisguised and naked,” he wrote, “I am mad for it to be in contact with me.” In Song of Myself, he praises “a well-made man,” saying, “dress does not hide him;/The strong, sweet, supple quality he has strikes through the cotton and flannel;/To see him pass conveys as much as the best poem, perhaps more;/You linger to see his back, and the back of his neck and shoulder-side.”

A few weeks ago, I was reading Walt Whitman, enthralled by the energy and rhythm of his poetry. It’s easy to see why he was embroiled in fights with 19th-century censors. “I will go to the bank by the wood and become undisguised and naked,” he wrote, “I am mad for it to be in contact with me.” In Song of Myself, he praises “a well-made man,” saying, “dress does not hide him;/The strong, sweet, supple quality he has strikes through the cotton and flannel;/To see him pass conveys as much as the best poem, perhaps more;/You linger to see his back, and the back of his neck and shoulder-side.”

And these are some of the milder passages. These probably aren’t the ones that got him fired from his job at the Department of the Interior and charged with “that horrible sin not to be mentioned among Christians.”

What’s most shocking about his writing today is not that he loves men or describes “the body electric.” What’s stunning is his democratic sensibility.

What a long way we’ve come. Whitman, who lived in Brooklyn for 28 years, would be astounded that New York has actually legalized same-sex marriage. He would have been equally amazed by a recent article in the New York Times about an effort to recruit more gays and lesbians into politics. And I’m sure his eyes would have widened a few weeks ago when the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond ran a rainbow flag up its flagpole at the request of a group of gay and lesbian employees in honor of gay pride month.

What a long way we’ve come. Whitman, who lived in Brooklyn for 28 years, would be astounded that New York has actually legalized same-sex marriage. He would have been equally amazed by a recent article in the New York Times about an effort to recruit more gays and lesbians into politics. And I’m sure his eyes would have widened a few weeks ago when the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond ran a rainbow flag up its flagpole at the request of a group of gay and lesbian employees in honor of gay pride month.

These events–especially the New York decision–are victories in the fight for gay and lesbian equality. New York has joined a handful of other states where people who love each other can make a legal commitment in a public ceremony and announce to the world at large: We are men and women with hopes and dreams. The promise of freedom, equality, and happiness in the Declaration of Independence applies to us, just as it applies to you.

And yet, as important as these victories are, and as critical to celebrate, they still leave me hoping that our country will live up to another ideal that struck me in Whitman’s poetry. Not only should everyone be free to love whomever they want and marry anyone they wish, but they should be able to work when they need to.

Today’s politicians and pundits seem to have forgotten the unemployed in their endless debates about wealth creation, capital gain reduction, and high corporate taxes. How rarely we hear about the factory worker, the contractor, the construction worker whose lives have been upended by the prolonged economic disaster. They’re not on the morning talk shows, or called to congressional hearings. They don’t write the op-ed pieces. Mostly they’re forgotten and ignored.

But Whitman wouldn’t have forgotten them. What’s most shocking about his writing today is not that he loves men or describes “the body electric.” What’s stunning is his democratic sensibility. He loves everyone. “I contain multitudes,” he wrote. He embraced the soul of democracy, its fundamental faith in humankind. He knew that the fate of each one of us is inextricably linked to the fate of all. “Whoever degrades another degrades me,” he wrote. “I speak the password primeval, I give the sign of democracy./By God, I will accept nothing which all cannot have their counterpart of on the same terms.”

But Whitman wouldn’t have forgotten them. What’s most shocking about his writing today is not that he loves men or describes “the body electric.” What’s stunning is his democratic sensibility. He loves everyone. “I contain multitudes,” he wrote. He embraced the soul of democracy, its fundamental faith in humankind. He knew that the fate of each one of us is inextricably linked to the fate of all. “Whoever degrades another degrades me,” he wrote. “I speak the password primeval, I give the sign of democracy./By God, I will accept nothing which all cannot have their counterpart of on the same terms.”

Where does this deep devotion come from? This isn’t someone who reduces the idea of democracy to an abstract concept like voting, or a knowledge of civics. He knows in his gut that people share so much, if only we had the eyes to see and the willingness to reach out to our fellow beings.

Whitman looks across America and sees himself in whomever he meets: “the horseman in his saddle,/Girls, mothers, house-keepers, in all their performances,/The group of laborers seated at noon-time with their open dinner-kettles, and their wives waiting,/The female soothing a child–the farmer’s daughter in the garden or cow-yard,/The young fellow hoeing corn.”

It’s ironic that Whitman chose to celebrate what we share at a time when Americans were less dependent on each other than we are today. Many more people lived on farms in the nineteenth century, and so they could be a lot more self-reliant: growing their own food, sewing their clothes, building their own homes. But rather than applauding what each American could do in isolation, Whitman embraced all of us together: “I hear America singing.”

Most of all, he loved to see Americans at work, using their broad arms as much as their brilliant minds. Images of working men and women leap from his pages, alive with power. We see “men that live among cattle or taste of the ocean or woods” alongside “the builders and steerers of ships and the wielders of axes and mauls, and the drivers of horses.”

Most of all, he loved to see Americans at work, using their broad arms as much as their brilliant minds. Images of working men and women leap from his pages, alive with power. We see “men that live among cattle or taste of the ocean or woods” alongside “the builders and steerers of ships and the wielders of axes and mauls, and the drivers of horses.”

Whitman often described the freedom of walking on the public road. The contrast with today’s world is telling. Now, Republicans see freedom not as walking on the public road, but as resisting taxation. The consequence–no public road. Extolling the value of self-reliance, Republicans have no answer for the person who studies hard, works hard, and then makes the mistake of working at a company whose CEO commits fraud and brings the organization down. It’s all very well to tell him to start his own company when the banks won’t lend.

Republicans have refused even to hold hearings for a Nobel Prize winner nominated to the Federal Reserve. His area of expertise? Employment. But Senator Shelby is more intent on protecting the wealthy, the ones whom Whitman describes like this: “Here and there with dimes on the eyes walking,/To feed the greed of the belly . . ./A few idly owning, and they the wheat continually claiming.”

Whitman contrasts these idle owners with the “Many sweating, ploughing, thrashing, and then the chaff for payment receiving.” His heart is with the many.

Whitman reminds us of another way of seeing ourselves and our world. He celebrates a nation where everyone is worthy, not where a few do well. In his America, we glory in our own work and we make sure there are jobs for everyone.

(Cross-posted, with permission from the author, at Atlantic.com)

Leave a Reply