By RP Staff, on Sun Jun 19, 2011 at 2:00 PM ET On Father’s Day when I was growing up, my Dad would play golf with some friends, do some work around the house and sit down me, my mother, brother and two sisters for dinner. Dinner usually consisted of standing rib roast, mashed potatoes and peas or string beans and, of course, iced tea. Dad would talk about golf which bored my mother and two sisters to pieces. My brother, still a mid-seventies golfer today, loved the golf gab.

The calm, normal family event on Father’s Days in the fifties and sixties contrasted greatly with Father’s Days my Dad spent in 1943-1945 when aboard a Coast Guard destroyer escort in the Atlantic. The Father’s Days of 43 and 44 reflect my father commanding his ship across the Atlantic on convoy protection duty.

June, 1945, the war in Europe ended and my father’s ship navigated the Panama Canal and headed for the North Pacific and the Aleutian Islands off Alaska. I was three that summer. By the time I was ten or so and gained some appreciation, my Dad’s pleasures were simple. He cut grass, fixed things that broke, taught me how to camp put in a pup tent and went to work. I do not recall the gifts we gave him, probably neck ties or a tool, but I do remember the dinners. The golf talk and the standing rib stand out, but so does my father, a dignified Coast Guard commander who passed away in 1998.

By RP Staff, on Sun Jun 19, 2011 at 1:30 PM ET Dad was a barber.

I grew up as a gay boy knowing this and knowing that my hair somehow did not deserve this atrocity. Seven years old is when I first, really, knew. Wanting to “grow my hair out” was NEVER an option.

This was 1969 and the only boys who had the Hair of Dreams did not have Barber Dads. They had Moms who would bring them in and have their “bangs trimmed”. Boys, mind you.

Bangs. Trimmed. Jealous. Angels. Jesus.

They would come into his northern KY barber shop with their beautiful hair

and I would be sweeping up after their gorgeous locks and wanting to save it. Savor it.

Not me. I had a buzz cut. Like a son of a chef who eats, not the lasagna served at the restaurant that evening, but whatever. Because, well, that’s what I do for a living and not for you. I’m tired.

My dad was awesome in so many ways, but not in Hair Ways.

I found some redemption and solace last week. I needed a hair cut, and tired of the whole Lexington Hair Scene (which I respect, no offense intended, Hair Gays), I decided , on a major South Broadway Starbucks mocha buzz to do something fiercely freeing.

I used the iPhone to search for “Barber” and ended up at Image Barbershop on Waller. 8am. They open at 7am. THAT, friends, is a Barber Shop.

Sat in The Chair. His tender care was immediately my Father. Gentle.

Closed my eyes and completely relaxed.

Then, in a moment of It Can’t Get Any Better Than This, it got: Better.

He steamed hot lather on my neck. And used an honest to Dad straight razor. And used talcum. Turned me around to look in the mirror and said, “How’s that?”

I have not felt that beautiful in a very long time.

Thank you, Dad.

More Michael J. Miller at his blog here.

By Loranne Ausley, on Sun Jun 19, 2011 at 1:15 PM ET

My dad, DuBose “Duby” Ausley, taught me everything I know about public service – he taught us, by example, the importance of serving your community, your family and your God with enthusiasm and integrity.

Although he has never held political office, he has been a quiet and effective leader his entire life. He was a Captain in the US Army, appointed by Presidents and Governors to serve in very important capacities, has had successful simultaneous careers in law and banking, and is still practicing law today.

Most recently, he served as one of the most important members of my team in our campaign for statewide office. While our efforts were not successful, it was a precious gift for a 47 year old daughter to be able to spend quality time working side by side with her 74 year old dad – still leading by example.

Thanks and Happy Father’s Day Dad!!!

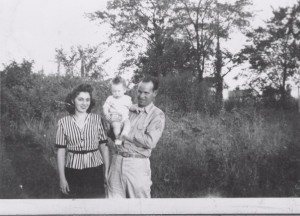

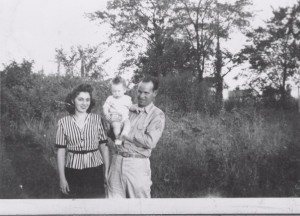

By RP Staff, on Sun Jun 19, 2011 at 1:00 PM ET  Mom, Dad and me My father was the oldest of nine living children when I was born. James

Dillon Mansfield had gone through the depression, worked at the Great

Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P) in high school, served in the

United States Army Air Corps during World War II where he was a desk sergeant, married literally the girl next door during the war, and eventually landed a job in their hometown of Ashland, Kentucky at Ashland Oil as a laborer. He was gradually promoted and ended up in management as a shift foreman, in charge of an entire refinery where he remained employed until he retired at age 62.

My oldest memories of him, include his being the disciplinarian in the

family, and one who spent a lot of time working when others would have

rested. He wasn’t afraid to use the “hickory stick” of which the song

speaks: “Reading and writing and arrhythmic, taught to the tune of a

hickory stick.” I remember hearing, “Just wait until your father gets

home” more than once. Since I was the one in the family most likely to

ignore rules I was also the one most likely to endure corporal

punishment. My Grandmother, though, said my parents were just learning

how to discipline through me rather than that I was too often the brat

in the family.

My absolute first memory of my father was when I was being “Mike” at

about age 5 and experimenting with the cigarette lighter my Uncle Bus

left behind after a visit. I managed to get my Uncle’s Zippo lit, then

set fire to the curtains, which set fire to the painted ceiling in my

“dormer-style” bedroom. It was then I realized I better tell on myself

and screamed for help. My father and mother both came upstairs; and one

of them tore the curtains down and stomped the fire out. Daddy realized

he had a quick way of putting out the fire. The bathroom was on the

other side of the room; and we had one of those rubber-hosed shower

heads for rinsing hair while taking a bath. While my Mom held it onto

the tub spigot, he pulled it as far into the bedroom as possible with

the water going full force. Somehow it reached far enough (probably

10-15 feet) to put out the fire! You don’t forget that kind of excitement.

As I said before, my father was a disciplinarian; but I do not remember

any punishment for setting that fire, what was probably the worst things

I did as a child or teen. I believe he had the wisdom to know I had been

punished enough by the immense fear this had caused me. It is possible I

was given some kind of corporal punishment or banished from play or

something else; but, if so, I have no memory of it but only of the fire

and my Dad’s quick action to save us and the house.

Another important thing about my Father was how much he knew about so

many things. This might not have been a special thing among his peers of

that; but I never knew anyone else who could do so many things so well.

He built the home in which I spent years 6-20. When I say he built it

literally. He dug the trench for the footer, mixed the concrete and

poured it, laid the block on which the frame was placed, put on the

siding, installed the windows and doors, laid the flooring, put in the

furnace and water heater, wired the entire home, and roofed it. He only

had help in two ways: Friends and family members helped raise the frame

since doing that as an individual would be very difficult or impossible.

Those friends and family would occasionally come just to help with

whatever he was doing that day, too. He hired someone to plaster the

inside walls and ceiling. He could weld, solder, work with electricity,

fix the car, and more things than I can remember.

He was not affectionate in a physical manner; but it would have been

difficult to deny that his love was there for the five of us and our

mother. As he got older he became a more demonstrative; but it was

difficult for him, just as it was once difficult for me.

One of the most dramatic memories I have of my father begins with the

arguments we would have about the War in Vietnam. We could never agree;

but the war eventually ended. Many years later, with no lead up, my

Father turned to me and said, “Mike, I was wrong about Vietnam.” It

wasn’t easy for him to admit when he was wrong; but this was far beyond

any usual disagreements we might have. This had to do with what the core

of the United States was about and even when a veteran would have to say

about that particular war. Later on Robert McNamara confirmed what we

both eventually believed about Vietnam.

I had a great mother. Perhaps I’ll get the chance to write about her on

a Mother’s Day in the future; but my Father had an awful lot to do with

the person I became, working hard, not giving up, and staying married

now forty-six years, almost as long as he and my Mother.

Thanks Daddy. I’ll miss you again this Sunday.

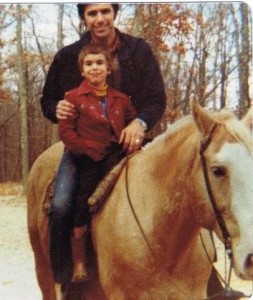

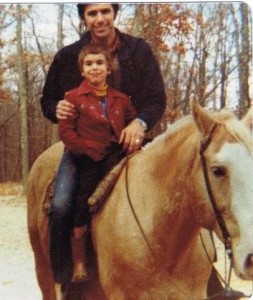

By Jonathan Miller, on Sun Jun 19, 2011 at 12:00 PM ET  My dad and I circa 1968 This piece — in which the RP honored his father and contributing RP Kathleen Kennedy Townsend’s father — first appeared at The Recovering Politician on April 4, 2011. We re-run it today.

Today — as on every April 4 — as the nation commemorates the anniversary of one of the worst days in our history; as some of us celebrate the anniversary of the greatest speech of the 20th Century; my mind is on my father. And my memory focuses on a winter day in the mid 1970s, sitting shotgun in his tiny, tinny, navy blue Pinto.

I can still remember my father’s smile that day.

He didn’t smile that often. His usual expression was somber, serious—squinting toward some imperceptible horizon. He was famously perpetually lost in thought: an all-consuming inner debate, an hourly wrestling match between intellect and emotion. When he did occasion a smile, it was almost always of the taut, pursed “Nice to see you” variety.

But on occasion, his lips would part wide, his green eyes would dance in an energetic mix of chutzpah and child-like glee. Usually, it was because of something my sister or I had said or done.

But this day, this was a smile of self-contented pride. Through the smoky haze of my breath floating in the cold, dense air, I could see my father beaming from the driver’s seat, pointing at the AM radio, whispering words of deep satisfaction with a slow and steady nod of his head and that unfamiliar wide-open smile: “That’s my line…Yep, I wrote that one too…They’re using all my best ones.”

He preempted my typically hyper-curious question-and-answer session with a way-out-of-character boast: The new mayor had asked him—my dad!—to help pen his first, inaugural address. And my hero had drafted all of the lines that the radio was replaying.

This was about the time when our father-son chats had drifted from the Reds and the Wildcats to politics and doing what was right. My dad was never going to run for office. Perhaps he knew that a liberal Jew couldn’t get elected dogcatcher in 1970s Kentucky. But I think it was more because he was less interested in the performance of politics than in its preparation. Just as Degas focused on his dancers before and after they went on stage—the stretching, the yawning, the meditation—my father loved to study, and better yet, help prepare, the ingredients of a masterful political oration: A fistful of prose; a pinch of poetry; a smidgen of hyperbole; a dollop of humor; a dash of grace. When properly mixed, such words could propel a campaign, lance an enemy, or best yet, inspire a public to wrest itself from apathetic lethargy and change the world. This was about the time when our father-son chats had drifted from the Reds and the Wildcats to politics and doing what was right. My dad was never going to run for office. Perhaps he knew that a liberal Jew couldn’t get elected dogcatcher in 1970s Kentucky. But I think it was more because he was less interested in the performance of politics than in its preparation. Just as Degas focused on his dancers before and after they went on stage—the stretching, the yawning, the meditation—my father loved to study, and better yet, help prepare, the ingredients of a masterful political oration: A fistful of prose; a pinch of poetry; a smidgen of hyperbole; a dollop of humor; a dash of grace. When properly mixed, such words could propel a campaign, lance an enemy, or best yet, inspire a public to wrest itself from apathetic lethargy and change the world.

Now, for the first time, I realized that my father was in the middle of the action. And I was so damn proud.

– – –

Click above to watch my eulogy for my father My dad’s passion for words struck me most clearly when I prepared his eulogy. For the past two years of his illness, I’d finally become acquainted with the real Robert Miller, stripped down of the mythology, taken off my childhood pedestal. And I was able to love the real human being more genuinely than ever before. The eulogy would be my final payment in return for his decades of one-sided devotion: Using the craft he had lovingly and laboriously helped me develop, I would weave prose and poetry, the Bible and Shakespeare, anecdotes and memories, to honor my fallen hero. In his final weeks of consciousness, he turned down my offer to share the speech with him. I will never know whether that was due to his refusal to acknowledge the inevitable, or his final act of passing the torch: The student was now the author.

While the final draft reflected many varied influences, ranging from the Rabbis to the Boss (Springsteen), the words were my own. Except for one passage in which I quoted my father’s favorite memorial tribute: read by Senator Edward Kennedy at his brother, Robert’s funeral:

My brother need not be idealized, or enlarged in death beyond what he was in life, to be remembered simply as a good and decent man, who saw wrong and tried to right it, saw suffering and tried to heal it, saw war and tried to stop it.

Read the rest of…

The RP: My Dad, RFK & the Greatest Speech of the Past Century

By Greg Harris, on Sun Jun 19, 2011 at 11:30 AM ET  I idolized my father growing up. I used to take friends up to his study to show them pictures from his old almanacs of his playing days in high school and college sports and brag about his athleticism. I bragged about him a lot as a kid, and still try to emulate him as an adult. I idolized my father growing up. I used to take friends up to his study to show them pictures from his old almanacs of his playing days in high school and college sports and brag about his athleticism. I bragged about him a lot as a kid, and still try to emulate him as an adult.

My dad took his profession very seriously, and it was really mom who played the more “hands-on” role growing up. Dad’s paternal example, my grandfather, was a tough Texas railroad man who was often on the road. In that generation, parents didn’t exactly “play” with their kids. My dad carried that tradition (albeit to a lesser extent). Indeed, I remember many days he’d come home from work for dinner, only to return to work after dinner.

But this was hardly a Harry Chapinesque “Cats in the Cradle” scenario—indeed, I always felt my dad was there for me and enjoyed me as a son. As busy as he was, I also never took for granted our bonding times—going to the local college’s basketball games (for which we had season tickets), the occasional Cubs game, the 20 hour drives to Texas to visit our kin, and the boxing. He taught me “the science of boxing,” and in my pre-teens we’d have periodic boxing matches in our family room when he’d don the gloves he brought me, sit at the end of the couch and let me come at him full speed while he’d lob soft “punches” in return. When I bobbed, weaved and got in a good punch, he’d fall backwards and feign like I knocked him out.

Strangely enough, my father became a far more hands-on parent in my adulthood. When I first ran for political office in 2002, my dad would literally commute from my South-of-Chicago hometown to Cincinnati every week to help with my congressional campaign. I was an unknown non-profit director at the time running against a very powerful incumbent. I got my butt kicked, but the consolation prize was the incredible “everyday” time I had with my father driving to church festivals and other campaign events. Many in Cincinnati’s political circles came to know my dad as a fixture on the campaign trail. Indeed in 2004, when I ran for congress a second time, my dad repeated the same ritual . . . commuting several hours each week to help out. By then, most politicos knew him, and it was more like a homecoming. That was a fun, spirited campaign in an intense presidential election year. But I was still very much the underdog, and when you are an underdog you often find yourself working like mad to win a race that no one thinks you can win, and often are met with ridicule by patronizing reporters and dismissive campaign donors that seem to take you less seriously for even trying. In those trying circumstances, having love and unconditional support in your corner is a God-send.

It was a bit off seeing a father who I looked up to my entire life undertake the role of a humble campaign worker . . . helping me with candidate surveys, marching in parades, handing out collateral at festivals . . . event after event. I remember vividly the day we were sitting side by side at computers in the campaign office when he suddenly announced “Paul Wellstone died in a plane crash.” (I am a graduate of Camp Wellstone, the late senator’s campaign organizing school.) I never got to win an election and taste victory with my father, which is one of my deep regrets, although I know he is no less proud of me.

I now have two sons, and so grateful they have the chance to interact with and get to know my father. He’s their “poppa.” He taught my 8-year old son Nathan last summer how to throw a spiral, and starred on stage for a community production of a Christmas Carol, which was my son’s first play.

I was blessed with two exceptional parents, but today is the day I pay tribute to my father. I firmly believe that every day I go about my work with conviction and integrity and stay true to my values is a day I’m befitting of his example. Next month I will turn 40, and very much hope that when my young sons are my age, they look back at me with a similar reverence for their old man.

My parents are the reason I have the courage to do what’s right, and have made this recovering politician feel like a winner even in defeat.

By RP Staff, on Sun Jun 19, 2011 at 11:00 AM ET  He said, “Share my life as an educator”. He said, “Share my life as an educator”.

Tuska was a husband, a father, a grandfather, a potter, a ceramist, a drawer, a sculptor, and an artist educator. He was a loving and giving person, on his terms. Meaning, if you wanted to be with him you had to work with him. I did.

Originally from Pennsylvania, raised and educated in New York, Tuska spent his life and career as an educator at the University of Kentucky, working, teaching, and never caring about self promotion. He lived in a self made bubble, inspired and inspiring, flourished and nurtured by his muse, Miriam, my mother.

I called him Dad, now and to others, just Tuska. Having no preconceived notion of the journey, I am spending the rest of my life, sharing his. However, when I look back, I now know why. I have been groomed for this my entire life.

My youth, while the emphasis was on the importance of education and a career away from art, self creativity and expression was always impressed upon. Spending every weekend in the Studio allowed “playing” with clay, having a pad of paper to draw, and surrounded by the processes and techniques he was immersed in. He always welcomed an assistant, and I was always willing. Any gift giving for birthdays and holidays had to be made. And I did.

In 1969, Tuska’s first sabbatical, moved us to Rome, Italy for the year. It changed us all. Non basta una vita, meaning one life is not enough, became the mantra. To Tuska, one would never be enough for all the things he wanted to say and do, as work generates work. And work he did.

I remember Tuska and I, as an 11 year old, were lying on the floor of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City as he is explaining not only the story of creation but Michelangelo’s process and technique of fresco. It impressed me so much, when we returned, a Seth “Creation” fresco found its way to the bathroom wall.

Flight of Icarus In 1974, Tuska was commissioned to do a piece for Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. Flight of Icarus, depicting a male tumbling figure in space. I spent three days with him, transporting and hanging the work, and without him in 2000 to hang it again.

As school became my job, while I would help with projects, attend castings, firings, and openings, math and science was my direction ahead. As high school turned to college, a structural engineering degree was in front of me and I wanted to build things.

As I weaned myself from the Tuska bubble and charted my own path as an engineer, a husband, and a father, I took with me the creative spirit and need as an artist, a self driven work ethic, an analytical mind, and a figure it out stubborn mentality as a visionary.

Tuska remained in his bubble, inspiring all who crossed his path, and continuing his work generates work mentality and lifestyle.

Tuska working on John Sherman Cooper bust In 1985 Tuska began his next major work, the John Sherman Cooper bust for the State of Kentucky. Unlike his other works, an honor he more than embraced. I remember helping him with the castings and found the pride as it was dedicated in the state capital.

It was when I became a father to two sons, the grand father Tuska emerged to play; unlike I had ever felt from him. It was a comfort to know he did relish life outside his work mode. But when they grew to be old enough, it was back in the studio to work with him as another generation of assistants.

The bubble pierced in the mid eighties as Tuska suffered medical crisis in bypass surgery and a stroke. It was very difficult to see him unable to work and having to depend on others. I could feel and see the frustration in him. But again, it was the muse who healed, nurtured, and pushed him back to work. The bubble was restored. And work he did.

Read the rest of…

Seth Tuska: John Regis Tuska — Life In the “Bubble”

By RP Staff, on Sun Jun 19, 2011 at 10:30 AM ET  (From L to R) David, Barry, Richard & Michael Snyder As a proud father of two amazing kids I get at double benefit this year as Fathers Day is also my 39th birthday. The fact is, that if I live to the ripe old age of 90, this will only occur 7 more times in my life so I want to savor each minute. This is a very special time in my life having made many changes to improve myself and my way of living. I am very much looking forward to sharing Fathers Day and my birthday with my own kids as well as my father.

My father and I have had our differences over the years but I have come to realize that we are much more alike than I ever thought. And for those that say older people are set in their ways and can’t (or won’t) change, I would challenge that because over the past while we have both been working to better our relationship and it working.

I have also had the joy, recently, to see my father at work which is something that I have never seen in person before and I was very proud to be sitting there next to him. To my father, I hope you have a wonderful day spending it with your kids and grandkids.

I love you,

Mike

By RP Staff, on Sun Jun 19, 2011 at 10:15 AM ET My father, Lowell Taylor, was diagnosed with stage IV prostate cancer in December 2007.

When I asked how I could pray for him, he said, “Please pray for two things- that I may continue to serve my Lord and others and that I will be able to bear the pain that is sure to accompany my illness.” That was it.

For the following 2 years and 4 months that he lived after diagnosis, he did all he could to serve other people even as his body was being destroyed from the inside out. In the last six weeks of his life, he planned his entire memorial service from choosing the hymns and their order, the speakers and musicians all with a decided theme of celebration.

The day of the memorial service came and people from 800 miles away participated as a gesture of thanks for the many ways he had served them. The service indeed was a celebration of the love he had for Jesus and Jesus had for him.

I hope my outlook would be so simple, yet so bold should I find myself in similar circumstances.

By RP Staff, on Sun Jun 19, 2011 at 10:00 AM ET

"Pop" Circa 1909-1910 On this Father’s day, while I’m being pampered, wined and dinned by my kids and grandkids, I know I’ll spend some time reminiscing about my Dad, “Pop”, as he was called by the many who knew him.

He was born in 1885 in the small village of Alt Breisach, Germany. He, his two brothers and three sisters, all ended up in America.

Pop settled in Louisville in Feb., 1913, after serving his stint in the German army. There he met my Mother, and they were married in November of that year. My older brother Sol was born in November, 1914, my sister Sylvia 4 years later, and me 5 years later.

At the height of the Depression, to avoid bankruptcy and to save our house from being foreclosed, Pop took on three jobs, working around he clock. To physically manage this, he sneaked in naps on his midnight to 8 A.M. shift as a nightwatchman in a downtown Hotel. My Pop, although not wealthy monetarily, had tons of wealth in his character, honesty, and his love and devotion to his family.

Although Pop didn’t have the financial means to help his first cousin, Emil Guggenheim, escape Hitler’s Germany, he did, with the aid of his employer, arrange for the financial backing necessary to bring the family over. Everything was arranged, then Poland was invaded and WW II began. He never heard from his cousin again.

A few months after Rita and I made the move to Lexington, Pop and Mom joined us here, taking a small apartment in Chevy Chase. Pop came to our office every single day and was dedicated to helping us succeed in the business venture I had chosen. All who knew him loved him.

After my Mother passed away in 1970, Pop moved in with us for the remaining four years of his life. I have fond memories of how he taught me German, from the song “Lili Marlene” to the poem “Roselein Rote, Roselein auf der Heiden”. Pop was ony in America ten years when I was born, so he and Mom still spoke a lot of German. He’s been gone 37 years now, but his light still shines brightly in my eyes.

|

The Recovering Politician Bookstore

|