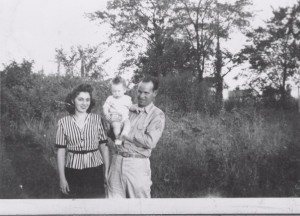

My father was the oldest of nine living children when I was born. James

Dillon Mansfield had gone through the depression, worked at the Great

Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P) in high school, served in the

United States Army Air Corps during World War II where he was a desk sergeant, married literally the girl next door during the war, and eventually landed a job in their hometown of Ashland, Kentucky at Ashland Oil as a laborer. He was gradually promoted and ended up in management as a shift foreman, in charge of an entire refinery where he remained employed until he retired at age 62.

My oldest memories of him, include his being the disciplinarian in the

family, and one who spent a lot of time working when others would have

rested. He wasn’t afraid to use the “hickory stick” of which the song

speaks: “Reading and writing and arrhythmic, taught to the tune of a

hickory stick.” I remember hearing, “Just wait until your father gets

home” more than once. Since I was the one in the family most likely to

ignore rules I was also the one most likely to endure corporal

punishment. My Grandmother, though, said my parents were just learning

how to discipline through me rather than that I was too often the brat

in the family.

My absolute first memory of my father was when I was being “Mike” at

about age 5 and experimenting with the cigarette lighter my Uncle Bus

left behind after a visit. I managed to get my Uncle’s Zippo lit, then

set fire to the curtains, which set fire to the painted ceiling in my

“dormer-style” bedroom. It was then I realized I better tell on myself

and screamed for help. My father and mother both came upstairs; and one

of them tore the curtains down and stomped the fire out. Daddy realized

he had a quick way of putting out the fire. The bathroom was on the

other side of the room; and we had one of those rubber-hosed shower

heads for rinsing hair while taking a bath. While my Mom held it onto

the tub spigot, he pulled it as far into the bedroom as possible with

the water going full force. Somehow it reached far enough (probably

10-15 feet) to put out the fire! You don’t forget that kind of excitement.

As I said before, my father was a disciplinarian; but I do not remember

any punishment for setting that fire, what was probably the worst things

I did as a child or teen. I believe he had the wisdom to know I had been

punished enough by the immense fear this had caused me. It is possible I

was given some kind of corporal punishment or banished from play or

something else; but, if so, I have no memory of it but only of the fire

and my Dad’s quick action to save us and the house.

Another important thing about my Father was how much he knew about so

many things. This might not have been a special thing among his peers of

that; but I never knew anyone else who could do so many things so well.

He built the home in which I spent years 6-20. When I say he built it

literally. He dug the trench for the footer, mixed the concrete and

poured it, laid the block on which the frame was placed, put on the

siding, installed the windows and doors, laid the flooring, put in the

furnace and water heater, wired the entire home, and roofed it. He only

had help in two ways: Friends and family members helped raise the frame

since doing that as an individual would be very difficult or impossible.

Those friends and family would occasionally come just to help with

whatever he was doing that day, too. He hired someone to plaster the

inside walls and ceiling. He could weld, solder, work with electricity,

fix the car, and more things than I can remember.

He was not affectionate in a physical manner; but it would have been

difficult to deny that his love was there for the five of us and our

mother. As he got older he became a more demonstrative; but it was

difficult for him, just as it was once difficult for me.

One of the most dramatic memories I have of my father begins with the

arguments we would have about the War in Vietnam. We could never agree;

but the war eventually ended. Many years later, with no lead up, my

Father turned to me and said, “Mike, I was wrong about Vietnam.” It

wasn’t easy for him to admit when he was wrong; but this was far beyond

any usual disagreements we might have. This had to do with what the core

of the United States was about and even when a veteran would have to say

about that particular war. Later on Robert McNamara confirmed what we

both eventually believed about Vietnam.

I had a great mother. Perhaps I’ll get the chance to write about her on

a Mother’s Day in the future; but my Father had an awful lot to do with

the person I became, working hard, not giving up, and staying married

now forty-six years, almost as long as he and my Mother.

Thanks Daddy. I’ll miss you again this Sunday.

Leave a Reply