By Artur Davis, on Wed Dec 19, 2012 at 9:15 AM ET Steven Spielberg delayed the release of his movie on Abraham Lincoln to avoid the charge of hagiography, not of the sixteenth president, but of Barack Obama. It was Spielberg’s intuition that there were enough aspects of the film that were susceptible to being twisted to partisan ends—from its similarity to the Democrats’ narrative of a progressive president fighting off a revanchist congressional opposition, to the Obama Administration’s early infatuation with Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals, which is credited as the primary source for the picture, to the linkage between the first American president to align himself with racial equality and the first president whose bloodlines crystallize that equality—to keep its premiere out of the election season.

So, “Lincoln” avoided becoming a bumper sticker in the final days of the last election. It has not managed to side-step a whole slew of efforts by commentators to make it an instructive template for political leadership: David Thomson’s assessment in the New Republic that the guiding principle of the film is the need for leaders “who can stoop to getting the job done” is mimicked by David Brooks’ assertion that the film elevates politics by showing the noble purposes to which ordinary political maneuvering can be deployed. Ross Douthat captures the argument that ”Lincoln” is a tribute to the revolutionary ends that can be achieved when moderates and ideologues align and temper each other.

I will venture a theory that while not one of these observations is wrong on the merits, that they all suffer from reading “Lincoln” through a certain wishful lens: in this light, Spielberg’s version (and Tony Kushner’s screenplay) of Abraham Lincoln is a model of what Barack Obama might develop into if he added more grit to the polish and the cool; or more broadly, this fictional president is an imagining of what any successful chief executive in the future might look like—savvy enough to coopt the hard-liners, tactical enough to accomplish heroic ends through hard-nosed means. In other words, these pundits see a high-minded primer on how a capable president might win friends and influence people: a home-spun, American Machiavelli.

But reading “Lincoln” as an instruction manual ignores the degree to which this film is almost subversively hostile to two of the favorite values of contemporary politics: authenticity and transparency. The blunt truth of this portrait of Lincoln’s presidency is a democratic reality that if it materialized tomorrow, we would find depressing and hardly idealistic. It is a closed universe of insiders who operated free of consistent public scrutiny, or ethics regulations, or even a softer code that words and deeds should be tightly connected to be credible. There is a void of disclosure and standards that is not remotely capable of being replicated today, and that we wouldn’t want to conjure up if we could. The point is not to treat Lincoln is anything other than great, but that his greatness operated in a zone not remotely like our own. But reading “Lincoln” as an instruction manual ignores the degree to which this film is almost subversively hostile to two of the favorite values of contemporary politics: authenticity and transparency. The blunt truth of this portrait of Lincoln’s presidency is a democratic reality that if it materialized tomorrow, we would find depressing and hardly idealistic. It is a closed universe of insiders who operated free of consistent public scrutiny, or ethics regulations, or even a softer code that words and deeds should be tightly connected to be credible. There is a void of disclosure and standards that is not remotely capable of being replicated today, and that we wouldn’t want to conjure up if we could. The point is not to treat Lincoln is anything other than great, but that his greatness operated in a zone not remotely like our own.

It is not just that Lincoln is “wily and devious”, in Thomson’s description in TNR, or that he takes “morally hazardous action”, in Brooks’ rendition, it is that the times he lived in extracted no particular price for such shiftiness. So, Lincoln saves the 13th Amendment at a critical stage by deploying a word game to fend off the news that a set of Confederate negotiators are offering a peace deal that might end the war without emancipation. The negotiators are not in Washington, Lincoln allows, despite rumors to the contrary and aren’t set to be there: the more complete truth is that they are holed up on the Virginia coastline, waiting for a presidential visit. The deceit is not a small one, and the movie to its credit captures both its importance and dishonesty: by bending the actual time line just a bit to make Lincoln’s dodging the decisive blow to enshrine freedom in the Constitution, Spielberg and Kushner are taking aim at our squeamishness over candor.

And it is not just the white lie over a southern peace offering. Another central point in the picture is the urgency of separating constitutional emancipation from a broader campaign to extend larger citizenship rights on blacks. In Spielberg’s mostly accurate telling, Lincoln’s rival for control of the House Republican caucus, Thaddeus Stevens (Tommy Lee Jones), equivocates at a key moment in the debate on the full implications of the amendment, and the film is complimentary of Stevens’ waffling, which is the exact rhetorical approach Lincoln himself brandished as a senate and presidential candidate and as the author of the Emancipation Proclamation. That it proved to be the shrewdest course in Lincoln’s day is hard to argue; what is impossible to argue is how aggressively such an evasion would be exploited in our climate (and how zealously we would argue for the dissembling to be unmasked if we were on the losing side).

Read the rest of…

Artur Davis: Lincoln’s Lost World

By Artur Davis, on Mon Dec 17, 2012 at 1:30 PM ET I am a conservative who believes that any philosophy is strengthened by reexamination. I do regard theory as a valuable measure of whether a policy has integrity, and the lawyer in me accepts that hard facts make bad law, and worse, can unfurl dangerously unintended consequences: but an ideology that can’t grasp the real-world consequences of its aims is deeply flawed. I am, it so happens, a defender of the Second Amendment who thinks that the right to own guns is privileged by some of the most explicit words contained in the Constitution. I also remember Lincoln’s admonition that a constitution is not a suicide pact that is oblivious to the ways history has reshaped us.

So, in that spirit, I acknowledge that in the last two years the gun debate has turned a corner. The slaughter of children, on top of the massacre of Sikhs in a temple, and moviegoers in a theater, and constituents at a congressional fair, demands that level of humility on the political right; arguably, it’s a corner that should have been turned earlier when bodies of inner city teenagers started piling up in morgues and assault weapons started outnumbering drug paraphernalia in crack houses.

The operative legal and moral question is how to frame a gun policy that reconciles our Constitution and the freedom of law abiding gun owners with the appalling ease of marginal, pathological drifters building a personal arsenal.

Liberals will need to concede that banning firearms altogether is undesirable as well as unconstitutional, and that prohibitionist rhetoric only aids and abets the NRA’s own absolutist stance. They will need to demonstrate a much sharper sensitivity to the fact that handguns do serve the ends of self-defense in both middle class suburbs and urban neighborhoods, and that hunting is part of the national cultural fabric: much too much of the leftwing punditry on this subject overflows with a barely disguised regional and class based contempt. In addition, advocates of stricter gun laws should drop the misleading implication that there are no meaningful barriers to gun ownership: to the contrary, they should be stressing that the Brady Bill’s waiting period and the longstanding prohibitions on gun ownership by felons or the institutionalized demonstrate pathways to strengthening public safety without shredding the liberties of law abiding gun owners. Liberals will need to concede that banning firearms altogether is undesirable as well as unconstitutional, and that prohibitionist rhetoric only aids and abets the NRA’s own absolutist stance. They will need to demonstrate a much sharper sensitivity to the fact that handguns do serve the ends of self-defense in both middle class suburbs and urban neighborhoods, and that hunting is part of the national cultural fabric: much too much of the leftwing punditry on this subject overflows with a barely disguised regional and class based contempt. In addition, advocates of stricter gun laws should drop the misleading implication that there are no meaningful barriers to gun ownership: to the contrary, they should be stressing that the Brady Bill’s waiting period and the longstanding prohibitions on gun ownership by felons or the institutionalized demonstrate pathways to strengthening public safety without shredding the liberties of law abiding gun owners.

At the same time, conservatives would do well to recognize that the fact that gun ownership is a right does not immunize it from regulation—no more than speech is shielded from defamation suits, or restrictions against inciting violence or using words to conspire to achieve a crime; no more than the free exercise of religion precludes scrutiny of whether churches are complying with the obligations of their tax exempt status, or of whether government grants to faith based institutions are being validly spent. Similarly, the roots that gun possession hold in our culture surely don’t carry more sociological sway than driving or marriage, both of which require some method of formal registration. Lastly, just as liberals ought to abandon their fictions around existing gun laws, conservatives should also admit that the existing regulations around guns have hardly marginalized gun ownership or created some unreasonable barrier to gun possession.

My own preferred approach would be to avoid outlawing classes of weapons, even the most lethal, semi-automatic versions: whether or not a hunting weapon can be distinguished from a killing machine is debatable, but even skeptics of that proposition must allow that the task of separating firearms based on their mechanical characteristics is too slippery to rely on, and too imprecise to offer gun manufacturers any predictable notice of whether they are crossing the line. But a strategy that focuses on discerning more about the humans who would own the guns (especially high impact firearms) makes sense. To be sure, constructing a licensing regime is a challenging enterprise: a firearms knowledge test would probably have had no impact on the self-taught nutjobs at work in Aurora and Newtown, much less the ex soldier in the Sikh shooting; a background check couldn’t be allowed to devolve into a profile that punishes the unemployed or the dropouts or the socially disconnected.

Read the rest of…

Artur Davis: The Emerging Moral Reality on Guns

By Artur Davis, on Tue Dec 4, 2012 at 1:30 PM ET The notion that a reelected Barack Obama would revert to the centrist, bipartisan sounding Obama of the 2008 campaign trail was a fantasy from its conception, and the White House officially punctured it with its release of a deficit plan that resembles a Democratic wish list: the death of the Bush era tax rates for upper income earners; a bump in the estate tax; for top brackets, a return to pre 2003 treatment of dividends as ordinary income rather than capital gains; a few carve-outs from 2011’s mini stimulus bill; and amorphous, undefined cuts to farm price supports, a rare spending reduction that enthuses the Democratic base. Entitlements are virtually left alone, save for a mystery round of “savings” in Medicare, with details to be named later.

It has the aesthetics of a maneuver rather than a genuine negotiating stance. And as maneuvers go, it is a skilled one. Offer a package thick enough with proposals to keep the high ground, but make it one-sided enough that Republicans will dismiss it, while counting on the GOP congressional base to keep unraveling to the point that sometime around Christmas Eve, Republicans yield on the two points that Democrats genuinely want from this exercise: a continuation of the Bush cuts for earners below $250,000, and another short-gap extension in jobless benefits. Of course, there aren’t a lunchtable’s worth of congressmen who seriously believe that once the White House has spared Democrats the vulnerability of defending seats in 2014 in the aftermath of a middle income tax hike, that Obama will return to the table to re-open the viability of the Bush top bracket cuts.

There are all manner of reasons to wonder why congressional Republicans saddled themselves with a dead-end that was so thoroughly predictable: from overconfidence about winning in 2012, to a momentary infatuation with the notion that the all but forgotten deficit super-committee would develop a deal-making prowess Washington has not seen in several generations, to an under appreciation of how much raising upper income taxes has become a politically cost-free goal for Democrats. There are all manner of reasons to wonder why congressional Republicans saddled themselves with a dead-end that was so thoroughly predictable: from overconfidence about winning in 2012, to a momentary infatuation with the notion that the all but forgotten deficit super-committee would develop a deal-making prowess Washington has not seen in several generations, to an under appreciation of how much raising upper income taxes has become a politically cost-free goal for Democrats.

The last blunder is worth dwelling on. To a degree Republicans were much too slow to realize, the political consequences around advocating for higher taxes have steadily declined over the last decade, to the point that three successive Democratic presidential campaigns have overtly favored a hike in upper income taxes. While Republicans have gamely protested that tax increases threaten job growth, Democrats have proved far more successful in fending off those claims with their own arguments that the tax code is too tilted toward the interests of top bracket earners. While the polling on the subject is partly a creature of a sample’s wording (exit polls showed a broad public preference for raising the tax burden on the “wealthy” coinciding with even stronger support for reducing the deficit primarily through spending cuts), there is virtually no evidence that a viewpoint exceedingly popular with the Democratic base has taken any electoral toll with swing voters.

Republicans are partly to blame for their own much less confident position. The closest Republicans have come to a comprehensive deficit strategy, Paul Ryan’s budget, has been only occasionally defended and its particulars remain obscure to most Americans who don’t frequent policy salons or Heritage Foundation online seminars. In fact, in an eerie echo of the Democratic play on health care reform in 2010, Republicans have invariably touted the Ryan Plan as a bold-hearted act of political courage while spending little energy on articulating its fine points. Nor have Republicans shown the strategic wherewithal to prioritize a single policy objective as dramatically and neatly defined as the Democratic aim of “making the rich pay their fair share.” Lastly, with their own rhetorical embrace of deficit reduction without the benefit of specificity, and by showing their own penchant for symbolic, but insubstantial gestures, Republicans paved the way for Democrats to wage their own disingenuous maneuver by overstating the impact of tax hikes that would only put a minor dent in the deficit.

So, what is a party to do, when it has been so constrained by its own miscalculations that it has almost no bargaining power? Assuming the administration does not have an outbreak of authentic compromise, congressional Republicans would do well to remember that their non-existent leverage will be enhanced the day sequestration takes effect and the mandatory cuts and revenue increases become a market and economic reality. With a newly strengthened hand, the onus would shift to Republicans to craft a detailed round of spending cuts, to become serious about downsizing corporate deductions, and to proffer a serious set of entitlement reforms, from partial means testing to restraining Medicare growth through a premium support based alternative. It would become an imperative for Republicans to conquer their own squeamishness about entitlements with the same nerve that has liberated Democrats from their fears about taxes.

Read the rest of…

Artur Davis: The Case for Republicans Walking Away from the Budget Talks

By Artur Davis, on Wed Nov 28, 2012 at 3:30 PM ET It is a measure of Chris Christie’s aura that serious people think his effusive praise of Barack Obama in the hours after Hurricane Sandy might have reelected the president. The likelier truth is that there are precious few undecided voters in Ohio and Virginia who know the name of the New Jersey governor, much less value his imprimatur as the tipping point in their electoral decision-making process. But Christie’s force of personality is one of the few authentic magnetic fields in politics that don’t bear the name Clinton or Obama, which guarantees disproportionate, even illogical, levels of attention when he makes moves.

That bravura suggests why Christie remains such an intriguing path for Republicans contemplating 2016. To be sure, there are mounting doubts about whether he is the one. The narrative that Christie is not a team player is gaining traction with Republican activists, who were confounded by the sound-bites of a Republican hero lavishing praise on the arch-enemy. The professional operative class that assesses political personalities for signs of trouble links his post-Sandy comments with a keynote address that seemed oblivious to the party talking points in Tampa, and they see a worrisome absence of discipline. The ones with a bent for pop psychology see brittleness masked as self-regard, and suggest that Christie must have been partly motivated by a fear of how difficult his reelection might be in a state Obama dominated, or even a burning fuse based on not being given a right of first refusal on the vice presidential nomination.

But the critiques on Christie are a reflection of the odd waters of modern politics. If Christie’s press conference seemed too much, it is largely because such post-disaster events are so typically sanitized with platitudes: In other words, public figures shrinking under the glare and resorting to a contrived, bland insincerity. The consensus that Christie underperformed in Tampa stems from a mindset that success on such stages is measured either by a cascade of glossy but insubstantial poetry or at the other end of the scale, a hard-edged partisanship. Surely, a politico with Christie’s game shouldn’t have spent his moment describing the minutiae of gubernatorial leadership; surely, if he outlined the national threat, it should have been in the form of a prolonged lease on the White House by the other party not in the possibility that both parties might be overwhelmed by the demands of the historic moment.

Read the rest of…

Artur Davis: Why Chris Christie Won’t Fade

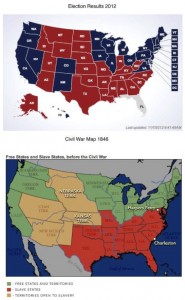

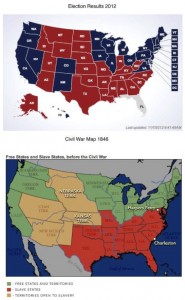

By Artur Davis, on Mon Nov 26, 2012 at 10:00 AM ET  I read Karen Cox’s provocative essay about what it takes to revive southern Democrats, (“A New Southern Strategy”), with a view that was doubtful from the start. There was the skepticism from having heard the logic before: it is a perennial preoccupation of southern progressives to envision an latent regional majority based on suburbanized whites, minorities, and educated professionals, although to date, Virginia and North Carolina are the sole places where the coalition seems to materialize and even then, only intermittently. Cox also does not acknowledge, much less grapple with, the fact that the South’s most rapid economic modernization has happened at the same pace and time as its decisive tilt toward Republicans, in direct contradiction of the progressive expectation. I read Karen Cox’s provocative essay about what it takes to revive southern Democrats, (“A New Southern Strategy”), with a view that was doubtful from the start. There was the skepticism from having heard the logic before: it is a perennial preoccupation of southern progressives to envision an latent regional majority based on suburbanized whites, minorities, and educated professionals, although to date, Virginia and North Carolina are the sole places where the coalition seems to materialize and even then, only intermittently. Cox also does not acknowledge, much less grapple with, the fact that the South’s most rapid economic modernization has happened at the same pace and time as its decisive tilt toward Republicans, in direct contradiction of the progressive expectation.

Then are the persistent factual blunders, from her conclusion that the Republican edge in the South is driven by outsized rural populations, when it is in actuality the suburbs outside the metropolitan cities that account for the consistent GOP advantage, to her glossing over the fact that southern big cities have tilted Democratic not so much out of their cosmopolitanism, or their burgeoning market in downtown lofts, but because their minority populations have steadily expanded (a misinterpretation Alec MacGillis takes her to task for in The New Republic).

More problematic than Cox’s treatment of data, though, is her threshold assumption that a more liberal South is an automatically enlightened place and that a more conservative South is a primitive dead zone that disdains modernity and ratifies the Old Confederacy’s historic pathologies. It’s the left’s stereotypical dichotomy of political polarization—but it is also a worldview that papers over the peculiar and more ideologically ambiguous disputes that dominate southern state capitals.

To be sure, there are conventional partisan battles in the South that mimic fights in Washington: whether to accept federal dollars to expand Medicaid, whether to set up the state exchanges created in the new healthcare law, and the aggressiveness of local immigration laws. But there is a much larger raft of region-specific policy dilemmas that thankfully don’t have a strong national analogue: they range from pervasive public corruption, to the explosion of a low wage casino culture in minority counties, to notoriously underfunded state universities, to tax structures that reverse federal policy by soaking low wage workers and families.

The fact is that those perennial challenges have been managed less by conservative Republicans, and more by Southern Democrats, who until the last few election cycles, still dominated state legislatures and held their share of governorships—trends with which many national observers are unfamiliar, as they erroneously assume that the deep red presidential voting patterns in the South have been as strong at the state level. Cox, a University of North Carolina historian, obviously knows better and must be aware of (1) the inconvenient truth that Democrats have had considerable governing responsibility during the South’s recent history and (2) the decidedly un-progressive ways Southern Democrats have used their powers. The fact is that those perennial challenges have been managed less by conservative Republicans, and more by Southern Democrats, who until the last few election cycles, still dominated state legislatures and held their share of governorships—trends with which many national observers are unfamiliar, as they erroneously assume that the deep red presidential voting patterns in the South have been as strong at the state level. Cox, a University of North Carolina historian, obviously knows better and must be aware of (1) the inconvenient truth that Democrats have had considerable governing responsibility during the South’s recent history and (2) the decidedly un-progressive ways Southern Democrats have used their powers.

At least one assumes she is. Does Cox actually understand that in Alabama, Democrats have only sporadically embraced reforming a state constitution that perpetuates one of the most sharply regressive tax structures in the nation, or that the state’s Democratic Party is funded primarily by a gambling lobby that enriches itself on the backs of the low wage poor? Would it be bothersome to Cox that the same gambling interests lavished huge campaign sums on an initiative to monopolize the state’s casinos in the hands of a couple of magnates, inside a few counties that are almost entirely black and impoverished? What about the effort the state Democratic Party spent trying to block an ethics package aimed at reducing lobbyist influence in state politics, the kind of good government crusade progressives salivate about at the national level?

To a depressing degree, the same elements that have warped Alabama’s Democratic Party into a weirdly retrograde force, at least on local issues, are equally present with their regional co-partisans—they include a faux populist aversion to elite supported reforms, an obsession with racial patronage politics, and a persistent trouble with raising money that leads to a few convenient if corrupting alliances.

Read the rest of…

Artur Davis: Toward a More Liberal South?

By Artur Davis, on Tue Nov 20, 2012 at 9:15 AM ET There are no ties weaker than the ones that bind politicians. So, no major surprise that surrogates who were just trumpeting Mitt Romney’s election as essential to the country’s future and celebrating his record as ideally suited to cracking open the partisan gridlock are doing their share of distancing from the defeated candidate. They have a lot to distance from: ranging from internal polling that was so off base it wasted the ticket’s precious time with last-minute campaigning in states they did not come close to winning, to Romney’s characterization of the Democratic base as tools whose affection was bought off by “gifts”.

But a cautionary note: Romney’s frustrations are the musing of a candidate legitimately perplexed by the Democrats’ ability to hold together a base that should have been frayed by the economic deterioration of the last four years. And if Republicans are being brutal but right about the politics of dismissing Romney, they are wrong if they ignore the question he was stabbing at: exactly how does a political majority keep intact when so many of its underlying policies aren’t exactly working in the interests of the coalition inside that majority? And if a flailing economy was not enough to weaken that base, what does that mean for the future given the unmistakable shifts in the national demographic?

Case in point: the African American solidarity behind Barack Obama in the face of severe black unemployment and poverty, and at the same time that Obama has aligned himself with a gay rights movement that is disdained by a consistent 30 to 40 percent of the black voter community. Another example is the 70 plus percent support Obama amassed from a Latino community that barely yielded him 50 percent approval ratings for much of 2011 and that was openly critical of his failure to push, much less pull off, comprehensive immigration reform. And for good measure throw in Obama’s sixty percent with voters 18-29 and more improbably, his ability to sustain their participation at 2008 levels despite months of polling evidence that the poor job market for young adults would diminish their enthusiasm.

Arguably, (and amusingly given the backlash from inside the party) Romney’s observations were only a clumsily put version of what numerous Republican commentators have said in a more sanitized way—that Democrats have nursed an entitlement culture that promises an engaged, assertive government to a variety of groups who are facing the imperfections of the free market. (Conservatives who argue that a softening of the GOP’s hard-line on immigration will be outweighed by Democratic pledges of more government benefits for Hispanics are channeling Romney). There is something to this assessment in its most reductionist form: between a health care law that has, for all its other imperfections, insured more young adults and low income minorities, to an executive order that eases off on the deportation of young undocumented immigrants, to a student loan reform that has cut the borrowing obligations of recent college undergraduates, the Obama administration has built a portfolio that delivered results for elements of its base that might have drifted.

Dismissing that record as a bounty of gifts was both impolitic and naive. There is nothing untoward or unpredictable in electoral groups siding with a party that has pursued initiatives friendly to their interests. But even the glossier version of Romney’ remarks, the pundit classes’ abstracting of initiatives that are base-friendly as an entitlement culture, is off-key because it underestimates exactly what else Democrats have managed to do. The more accurate assessment is that Democrats have stitched together a coalition that is linked less by dependency on government than by a shared perception of Republican and conservative insularity. Dismissing that record as a bounty of gifts was both impolitic and naive. There is nothing untoward or unpredictable in electoral groups siding with a party that has pursued initiatives friendly to their interests. But even the glossier version of Romney’ remarks, the pundit classes’ abstracting of initiatives that are base-friendly as an entitlement culture, is off-key because it underestimates exactly what else Democrats have managed to do. The more accurate assessment is that Democrats have stitched together a coalition that is linked less by dependency on government than by a shared perception of Republican and conservative insularity.

Republicans who marvel at the loyalty of the 08 Obama coalition fail to appreciate that the coalition was and remains socially aspirational rather than economic. Its foundation is a yearning for a culture that is stripped of its ethnic and social boundaries and hierarchies, an embrace of diversity as a strength rather than a source of disarray, and a suspicion that conservative individualism is both un-cool and at odds with the wired, interconnected reality of the 21st century. It should have been no surprise that the black/Latino/youth base responded so powerfully to Democratic insinuations that Obama’s defeat would mean a retreat from a modernist notion of American identity, and that consolidating that identity proved more compelling than jobless numbers (especially when Obama’s argument that Republican intransigence was more at fault than his own policies took hold).

To be sure, the Obama campaign did not trust its appeal entirely to inspiration. There was a healthy dose of fear-mongering: witness the demonization of voter ID laws, which Democratic operatives relentlessly painted as a scheme to suppress minority and youth turnout, as well as the allegations from Obama allies that ordinary Republican partisanship was deep seated revanchism and white backlash.

That Republicans minimized this demonization while it was in progress meant that it was rarely answered. GOP strategists comforted themselves with assumptions that liberals were practicing an identity politics that would backfire, or that cold economic realities would thwart the Democrats’ tactics, or at least constrain their turnout. Instead, the best evidence is that Democrats pulled off the feat of turning Republican orthodoxy into a cultural identity in its own right, one that was white, traditional and unattractively reactionary. The result was a galvanized Obama base that shattered Republican voter models.

Read the rest of…

Artur Davis: The Real Reason Democrats Held Their Base

By Artur Davis, on Fri Nov 16, 2012 at 1:30 PM ET The Republican self-assessments, and the hardly disinterested kibbitzing from liberal pundits, are as scattered as would be expected in the wake of last week’s defeat. Some of the ideas have the virtue that they at least were not implicated in a 2012 strategy that failed. But in world where all rationalizations are not created equally, it’s worth dwelling on some of the more problematic pieces of advice floating around the atmosphere.

Hold firm on immigration. Hold firm on immigration.

Laura Ingraham, Ross Douthat and others have sounded the alarm that a Republican embrace of immigration reform, which they label presumptively as amnesty, will fail because Democrats will simply raise the bidding by promising Hispanics ever more government benefits and largess. They are right that immigration is no panacea. For one thing, any immigration reform remotely palatable to conservatives will not treat all undocumented immigrants alike, and the GOP’s likely preference for privileging families and long time residents will be challenged by Democrats who favor a dusted off version of the abandoned 2006 McCain Kennedy bill, which drew no such distinctions. An Obama Administration that clung to the position that virtually any state based immigration standards were illegal is extremely unlikely to accommodate the inevitable conservative preference for an approach more respectful of federalism. In other words, Republicans entering the immigration fight will not be greeted with an olive branch.

But a softening of the Republican hard-line on immigration is frankly not about co-opting the left. It is, instead, recalibrating the GOP line so it is not so easily cast as a reflexive backlash at a surge in the Hispanic population. The orthodoxy in the Republican primaries and in the Fox universe was even in its best light, contradictory of conservative impulses: for example, an avowedly pro-family party was averse to making the consolidation of families a linchpin of immigration policy and a party that is determined to tie welfare benefits to responsible behavior seemed uninterested in a Dream Act aimed at promoting college attendance and enrollment in the military. An immigration view that seemed suspiciously adrift from the usual conservative values couldn’t help but be seen as a code for a much worse instinct.

Of all of the left’s cultural bogeymen this past cycle—voter ID laws, Republican resistance to gay rights, and the anti-immigrant mantra—none affected a larger swath of swing voters than the immigrant bashing charge. A Hispanic electorate that barely gave Barack Obama 50 percent approval ratings for much of 2011 crested at 70 plus percent support for the president on Election Day. The size of the Hispanic deficit doomed Romney in Nevada and Colorado, and Democrats are right that a repeat in 2016 could arguably put Arizona and Texas in jeopardy.

Join Obama’s grand compromise.

There is much truth to the notion that Obama effectively framed this election as a choice between a middle class champion and a millionaire coddling plutocrat. To be sure, the Republican Party needs to shed its royalist economic image. While that likely does not mean embracing a breakup of big banks or the decentralization of the capital markets structure (Craig Shirley’s ideas in the Washington Post) it would make ample sense for Republicans to adopt the kind of smart, market oriented ideas Douthat and Reihan Salam have extolled for awhile, and as Governor Bobby Jindal proffered this week, to make that kind of conservative innovation a leading edge of the party’s rhetoric.

But morphing into a more middle-class friendly party does not inevitably mean yielding on the cornerstones of the current economic debate, by acquiescing on Obama’s proposed tax hikes on the wealthy or retreating from a spending cut focused approach to downsizing the deficit. In fact, the compromise that a rising number of top rank CEOs are urging, letting go the Bush tax rates for earners above $500,000 in exchange for a phased in reduction of the corporate rate, is a classic example of a pragmatic seeming position that is actually quite deferential to the Republican donor base. The party’s donors and lobbyists would invariably trade a marginal rate boost that their accountants could trim away to holding the status quo on reams of corporate deductions.

Hence, the weakness of cosmetic positions that are badly flawed in practice, but accomplish some strategic repositioning. It is actually to Mitt Romney’s credit that he rejected a quick-fix middle income tax cut during the primaries, and unlikely that a Romney embrace of the Simpson Bowles Commission would have done anything other than saddle him with rolling back the popular mortgage deduction. The impact of the Ryan Plan remains debatable, but given that seniors gave Obama a negligible edge on Medicare, one smaller than the Democratic edge on the subject in the last two presidential cycles, it is also a stretch to say that the shrewdest future course is silence on entitlements.

Count on an increase in the GOP’s African American vote.

Perhaps in the interest of holding ground on immigration and ceding an outsized Hispanic vote in perpetuity, there is an emerging school of thought that the easier route might be to target a notably higher African American vote than Romney’s 7 percent, which itself was an over-performance from summer polls showing virtually no black votes for Romney( not to pick on Douthat again, but there are strong traces of this analysis in his last column and it is an emerging favorite of African American Republican bloggers).

The math seems unassailable. Running up the black vote to low double digits would do wonders to Republican numerical calculations for future races (or perhaps it would compensate for the unwisely understated assumptions this cycle about black turnout). The challenge for Republicans is that no nominee has reached those levels of blacks support since 1972 and only George W. Bush in 2000 has crossed the ten percent line, and then only barely.

There are usually two dubious assumptions at the base of an African American strategy for Republicans. The first, that the near monolithic black vote is a function of a superior outreach machinery by Democrats, and that Republicans could lessen the gap with a more assertive deployment of advertising or social media. Second, the idea that there is a suppressed black conservative vote that could be activated by more artful use of themes like opposition to same sex marriage.

Both theories downplay the extent to which the black advantage for Democrats is a reflection of one community’s entrenched skepticism of the Republican label as well as its considered judgment that active Democratic style government intervention is in its best interest. That mindset is only hardened by the near universal belief in black circles that Obama has faced uniquely vigorous opposition from Republicans for racially tinged reasons.

A Republican candidate who came to verbal blows with the Tea Party and the GOP’s southern wing and who was an avowed moderate would have a head start on gaining ground with blacks; so for that matter would a socially conservative Democrat who criticized, say, gay influence in the Democratic Party have a running start at securing more white Southern evangelical support. Neither variant has a remote shot of emerging in the current left-right duopoly of American politics. Absent the wildly improbable, or the inclusion on a Republican ticket of Condi Rice, there is no empirical reason to think that in the short term, Republican percentages in the black electorate would rise more than a point or so to average post Nixon levels. (In fact, a smaller black turnout post Obama would wipe out the gain from returning to Bush 2000 support levels).

These aren’t disastrous ideas—don’t over-assume the benefits of a turnabout on immigration; lose the image of being the party of No; and rediscover the tradition of Lincoln—but they miss in different ways what, in the context of race, conservatism has done to itself and in the context of economics, the nature of the cards we are dealt. This road back is a long one.

(Cross-posted, with permission of the author, from OfficialArturDavis.org)

By Artur Davis, on Mon Nov 12, 2012 at 8:10 AM ET  Well before Bill Clinton mastered the skill of political survival, and became the most consequential ex-president since Theodore Roosevelt, he pulled off a more pivotal achievement. Clinton essentially restored the Democratic Party as an electoral force by shoring up its credibility on fiscal policy, social policy, and race, and in so doing, he drew two crucial blocs firmly back into his party: blue collar whites and suburban professionals. The modern electoral map, which allots most of the industrial north and Midwest to Democrats and in which suburb-heavy states like California and New Jersey have not been contested in a generation, is the legacy of Clinton’s restoration project. Well before Bill Clinton mastered the skill of political survival, and became the most consequential ex-president since Theodore Roosevelt, he pulled off a more pivotal achievement. Clinton essentially restored the Democratic Party as an electoral force by shoring up its credibility on fiscal policy, social policy, and race, and in so doing, he drew two crucial blocs firmly back into his party: blue collar whites and suburban professionals. The modern electoral map, which allots most of the industrial north and Midwest to Democrats and in which suburb-heavy states like California and New Jersey have not been contested in a generation, is the legacy of Clinton’s restoration project.

Republicans face a comparable predicament to the one pre-Clinton Democrats faced in the late eighties, and to compound the analogy, it is a challenge along roughly the same fronts with a very similar alignment of voter blocs. If Walter Mondale’s Democrats seemed wedded at the hip to their union benefactors, today’s Republicans seem just as tied to corporate lobbies or billionaires. If the party that nominated George McGovern seemed mired in the grip of left-leaning activists bent on a radical redesign of social policy, Republicans appear to be under the sway of one network and a bevy of factions who are just as bent on a counter-cultural revolution from the right. The combination of money and noise exerted veto power on late eighties Democrats, much as contemporary Republicans are constrained by their own base.

And the blue collars and suburbanites whom Clinton strategized over are the very same slices of the electorate that allowed Barack Obama to run the battleground table with the exception of North Carolina (whose unpopular Democratic governor and nine percent plus unemployment should have made a 2.5 point margin much more comfortable). And the blue collars and suburbanites whom Clinton strategized over are the very same slices of the electorate that allowed Barack Obama to run the battleground table with the exception of North Carolina (whose unpopular Democratic governor and nine percent plus unemployment should have made a 2.5 point margin much more comfortable).

The particulars of the Clinton project are worth recalling. The adoption of welfare reform served as an antidote to voters who associated Democrats with the transfer of tax dollars to the irresponsible. The denunciation of a rapper for loose lyrics about police violence seemed to erase the pandering, excuse making side of the party’s DNA. The now forgotten middle class tax cut proposal may not have survived Clinton’s first budget cycle, but it did its job by linking his party to the economic fortunes of a group that hadn’t seemed needy enough to be a liberal priority.

My strong hope is that Republicans, my new party, are about to discover their Clinton instincts. Had those sensibilities surfaced in the last ninety days, Mitt Romney would likely be planning a transition now. It is not hard to imagine the impact of a well-timed denunciation of the Todd Akin/Richard Murdock mythologies on rape not as gaffes, but as wrong-headed efforts to have government substitute for the conscience and moral judgment of a victimized woman. A fleshed out plan to rescue homeowners underwater on ill-conceived mortgages would have reflected some of the smarter instincts in the conservative intelligentsia in the last several years, while paying dividends with voters who associated the GOP with the blocking of initiatives and little else. Grabbing and running with Senator Marco Rubio’s version of the Dream Act before Obama absconded with it would have made a difference in Florida and Colorado.

But the tactical missed chances by Romney’s operation are history. The current challenge is finding a GOP pathway to do on the right what Clinton did in the salvation of the left 20 years ago: first, restoring the party’s bona fides as an institution capable of thinking and governing and not just pawing under the commands of its base. Second, overcoming a resistance to smart, fiscally disciplined innovation and reform.

Read the rest of…

Artur Davis: The New Republicans

By Artur Davis, on Fri Nov 9, 2012 at 1:30 PM ET  When all was said and done, this election did turn out to be 2004 again. A polarizing president with tepid approval ratings fended off a Massachusetts based challenger who proved surprisingly resilient, but whose tactical errors and vulnerabilities put an unbreakable ceiling on his appeal. The victory itself was a weirdly shaped bubble made partly of scaring up a base vote with ad hominem attacks on the persona and character of the opponent, and partly of one time, single issue alliances that lifted the beleaguered incumbent without gaining much for his ballot mates in his own party: In George W. Bush’s case, a same sex marriage ban that doubled the normal black Republican vote in Ohio, in Barack Obama’s, an adept use of Mitt Romney’s opposition to the automobile industry bailout to bolster Democratic white working class support in Ohio. When all was said and done, this election did turn out to be 2004 again. A polarizing president with tepid approval ratings fended off a Massachusetts based challenger who proved surprisingly resilient, but whose tactical errors and vulnerabilities put an unbreakable ceiling on his appeal. The victory itself was a weirdly shaped bubble made partly of scaring up a base vote with ad hominem attacks on the persona and character of the opponent, and partly of one time, single issue alliances that lifted the beleaguered incumbent without gaining much for his ballot mates in his own party: In George W. Bush’s case, a same sex marriage ban that doubled the normal black Republican vote in Ohio, in Barack Obama’s, an adept use of Mitt Romney’s opposition to the automobile industry bailout to bolster Democratic white working class support in Ohio.

But winning in uninspiring form counts just as much as the grand sweeps like 1980 and 2008. The Republican Party’s defeat unmasks deep liabilities beyond the expected demographic shortcomings with Latinos and voters under 29 (who against all expectations, maintained their slice of the electorate at 2008 levels in the midst of an appalling job market for new college graduates). The electorate rejected Romney even in the face of exit polls showing that voters trusted Romney to handle the economy better than Obama; that they overwhelmingly viewed the economy as poor or mediocre; that they favored repeal of Obama’s signature healthcare initiative; and that they rejected Obama’s strategy of deficit reduction through tax increases.

The conservative base is smaller than it has been in three decades, with its share falling to 35% while liberals edged up to 24%, a narrowing advantage further diminished by the fact that about a fifth of that conservative base consists of blacks and Latinos who still overwhelmingly voted for Obama. The Republican conservative base seems perilously close to shrinking to white southern evangelicals, senior white males, and upper income Protestants.

That Obama more or less maintained the 2008 foundation of his victory, with the exception of North Carolina and Indiana, is especially striking given the weak-kneed nature of the Obama recovery and the fact that close to half the country now views the president, a figure once ascribed near mythical powers, in an unfavorable vein. One unavoidable conclusion is that the country’s skepticism toward the last four years was outweighed by a marginally wider distrust of what Republican rule would look like. Another is that the electorate’s affinity for individual elements of the Republican agenda never coalesced into their approval of a broader GOP governing vision. That Obama more or less maintained the 2008 foundation of his victory, with the exception of North Carolina and Indiana, is especially striking given the weak-kneed nature of the Obama recovery and the fact that close to half the country now views the president, a figure once ascribed near mythical powers, in an unfavorable vein. One unavoidable conclusion is that the country’s skepticism toward the last four years was outweighed by a marginally wider distrust of what Republican rule would look like. Another is that the electorate’s affinity for individual elements of the Republican agenda never coalesced into their approval of a broader GOP governing vision.

Hence the seemingly conflicted choice to pair Obama with a Republican House that surrendered few members of its majority beyond districts with a history of Democratic strength. Keeping the House red preserves the check on the unpopular aspects of Obama’s rule, while electing Romney would have meant sanctioning a policy course that remained nebulous or disconcerting to many swing voters and moderates.

To be sure, a better crafted campaign would have filled in Romney’s policy goals more convincingly than the ritualistic invocation of five point plans and generic references to cutting regulation and producing more domestic energy. But that failure is not just a marketing flaw on the part of Romney’s ad men: it is a symptom of a modern conservatism that seems spent and resistant to innovation on some days, purely oppositional and reactive on other days. And the weightiest part of the recent conservative agenda, Paul Ryan’s budget plan, was barely mentioned and its details only intermittently defended. (The details of Ryan’s budget had their share of political pitfalls, but the scant attention to it by the Romney campaign surely contributed to the impression that the Republican wish list was being kept deliberately shadowy.)

The other risk for Republicans, as Fox News’ Britt Hume noted last night, is that the axis of gravity is shifting leftward, and that a center right electorate is more predisposed than ever to a view that equates conventional conservatism with a middle aged backwardness. The hardening of the Democratic edge in affluent Northern Virginia, the white professional female gender gap, and the historically poor Republican showing with Hispanics can all be linked to a value judgment about the insularity of the Republican coalition. It is not hard to imagine that Democrats will exploit their growing cultural edge by pushing harder on issues that seemed marginal a cycle ago, like a fifty state right of same sex marriage, or more aggressive regulation of faith based institutions.

Read the rest of…

Artur Davis: The Republican Dilemma

By Artur Davis, on Mon Oct 29, 2012 at 10:00 AM ET  If it turns out the life of Barack Obama’s presidency is measured in months, left-leaning analysts will agonize over what went so wrong. Their explanations will range from confusion over how a stunningly gifted orator never mastered the greatest national pulpit, to consternation about the intransigence of Republicans and the eruption of the Tea Party, to sober hand-wringing about the intractable nature of 21st Century democracy. If it turns out the life of Barack Obama’s presidency is measured in months, left-leaning analysts will agonize over what went so wrong. Their explanations will range from confusion over how a stunningly gifted orator never mastered the greatest national pulpit, to consternation about the intransigence of Republicans and the eruption of the Tea Party, to sober hand-wringing about the intractable nature of 21st Century democracy.

But the mourning will not match the genuine misery and perplexity many Americans feel regarding the state of the nation. For all the explanations of how Obama has fallen short of his promise, the simplest one is in the discontent of those 23 million plus individuals who are under or unemployed, some for such long stretches that they have fallen through the cracks of the government’s official statistics. These men and women are the source of a national fury over why things are the way they are, and they and the Americans who know them have proved resistant to deflecting responsibility or changing the subject.

To be sure, as his defenders never cease to point out, Obama was greeted with the debris of a national calamity. The country seemed to be teetering on the edge of depression for stretches in late 2008 and early 2009, a casualty of a Washington environment that privileged and made unaccountable the giant government sponsored housing enterprises and a reckless Wall Street culture that took the risk out of lending for the mortgagor. But rather than tackle the crisis with single-mindedness, Obama veered off in too many scattered directions: a stimulus whose legacy is a slew of poor returns on investments in alternative energy and uncompleted construction projects, a partisan healthcare law that drained off a year of the administration’s efforts, a massive overhaul of the carbon producing economy that was too unwieldy for even many Democrats to embrace, a financial industry bill that has not stopped excessive leveraging in the capital markets. The portfolio is one that Obama and his allies have strained to explain, much less justify. To be sure, as his defenders never cease to point out, Obama was greeted with the debris of a national calamity. The country seemed to be teetering on the edge of depression for stretches in late 2008 and early 2009, a casualty of a Washington environment that privileged and made unaccountable the giant government sponsored housing enterprises and a reckless Wall Street culture that took the risk out of lending for the mortgagor. But rather than tackle the crisis with single-mindedness, Obama veered off in too many scattered directions: a stimulus whose legacy is a slew of poor returns on investments in alternative energy and uncompleted construction projects, a partisan healthcare law that drained off a year of the administration’s efforts, a massive overhaul of the carbon producing economy that was too unwieldy for even many Democrats to embrace, a financial industry bill that has not stopped excessive leveraging in the capital markets. The portfolio is one that Obama and his allies have strained to explain, much less justify.

Read the rest of…

Artur Davis: A Closing Argument for Mitt Romney

|

|

But reading “Lincoln” as an instruction manual ignores the degree to which this film is almost subversively hostile to two of the favorite values of contemporary politics: authenticity and transparency. The blunt truth of this portrait of Lincoln’s presidency is a democratic reality that if it materialized tomorrow, we would find depressing and hardly idealistic. It is a closed universe of insiders who operated free of consistent public scrutiny, or ethics regulations, or even a softer code that words and deeds should be tightly connected to be credible. There is a void of disclosure and standards that is not remotely capable of being replicated today, and that we wouldn’t want to conjure up if we could. The point is not to treat Lincoln is anything other than great, but that his greatness operated in a zone not remotely like our own.

But reading “Lincoln” as an instruction manual ignores the degree to which this film is almost subversively hostile to two of the favorite values of contemporary politics: authenticity and transparency. The blunt truth of this portrait of Lincoln’s presidency is a democratic reality that if it materialized tomorrow, we would find depressing and hardly idealistic. It is a closed universe of insiders who operated free of consistent public scrutiny, or ethics regulations, or even a softer code that words and deeds should be tightly connected to be credible. There is a void of disclosure and standards that is not remotely capable of being replicated today, and that we wouldn’t want to conjure up if we could. The point is not to treat Lincoln is anything other than great, but that his greatness operated in a zone not remotely like our own.

Liberals will need to concede that banning firearms altogether is undesirable as well as unconstitutional, and that prohibitionist rhetoric only aids and abets the NRA’s own absolutist stance. They will need to demonstrate a much sharper sensitivity to the fact that handguns do serve the ends of self-defense in both middle class suburbs and urban neighborhoods, and that hunting is part of the national cultural fabric: much too much of the leftwing punditry on this subject overflows with a barely disguised regional and class based contempt. In addition, advocates of stricter gun laws should drop the misleading implication that there are no meaningful barriers to gun ownership: to the contrary, they should be stressing that the Brady Bill’s waiting period and the longstanding prohibitions on gun ownership by felons or the institutionalized demonstrate pathways to strengthening public safety without shredding the liberties of law abiding gun owners.

Liberals will need to concede that banning firearms altogether is undesirable as well as unconstitutional, and that prohibitionist rhetoric only aids and abets the NRA’s own absolutist stance. They will need to demonstrate a much sharper sensitivity to the fact that handguns do serve the ends of self-defense in both middle class suburbs and urban neighborhoods, and that hunting is part of the national cultural fabric: much too much of the leftwing punditry on this subject overflows with a barely disguised regional and class based contempt. In addition, advocates of stricter gun laws should drop the misleading implication that there are no meaningful barriers to gun ownership: to the contrary, they should be stressing that the Brady Bill’s waiting period and the longstanding prohibitions on gun ownership by felons or the institutionalized demonstrate pathways to strengthening public safety without shredding the liberties of law abiding gun owners.

Follow Artur: