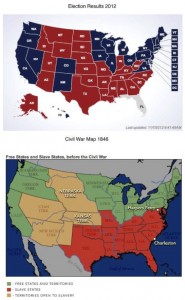

I read Karen Cox’s provocative essay about what it takes to revive southern Democrats, (“A New Southern Strategy”), with a view that was doubtful from the start. There was the skepticism from having heard the logic before: it is a perennial preoccupation of southern progressives to envision an latent regional majority based on suburbanized whites, minorities, and educated professionals, although to date, Virginia and North Carolina are the sole places where the coalition seems to materialize and even then, only intermittently. Cox also does not acknowledge, much less grapple with, the fact that the South’s most rapid economic modernization has happened at the same pace and time as its decisive tilt toward Republicans, in direct contradiction of the progressive expectation.

I read Karen Cox’s provocative essay about what it takes to revive southern Democrats, (“A New Southern Strategy”), with a view that was doubtful from the start. There was the skepticism from having heard the logic before: it is a perennial preoccupation of southern progressives to envision an latent regional majority based on suburbanized whites, minorities, and educated professionals, although to date, Virginia and North Carolina are the sole places where the coalition seems to materialize and even then, only intermittently. Cox also does not acknowledge, much less grapple with, the fact that the South’s most rapid economic modernization has happened at the same pace and time as its decisive tilt toward Republicans, in direct contradiction of the progressive expectation.

Then are the persistent factual blunders, from her conclusion that the Republican edge in the South is driven by outsized rural populations, when it is in actuality the suburbs outside the metropolitan cities that account for the consistent GOP advantage, to her glossing over the fact that southern big cities have tilted Democratic not so much out of their cosmopolitanism, or their burgeoning market in downtown lofts, but because their minority populations have steadily expanded (a misinterpretation Alec MacGillis takes her to task for in The New Republic).

More problematic than Cox’s treatment of data, though, is her threshold assumption that a more liberal South is an automatically enlightened place and that a more conservative South is a primitive dead zone that disdains modernity and ratifies the Old Confederacy’s historic pathologies. It’s the left’s stereotypical dichotomy of political polarization—but it is also a worldview that papers over the peculiar and more ideologically ambiguous disputes that dominate southern state capitals.

To be sure, there are conventional partisan battles in the South that mimic fights in Washington: whether to accept federal dollars to expand Medicaid, whether to set up the state exchanges created in the new healthcare law, and the aggressiveness of local immigration laws. But there is a much larger raft of region-specific policy dilemmas that thankfully don’t have a strong national analogue: they range from pervasive public corruption, to the explosion of a low wage casino culture in minority counties, to notoriously underfunded state universities, to tax structures that reverse federal policy by soaking low wage workers and families.

The fact is that those perennial challenges have been managed less by conservative Republicans, and more by Southern Democrats, who until the last few election cycles, still dominated state legislatures and held their share of governorships—trends with which many national observers are unfamiliar, as they erroneously assume that the deep red presidential voting patterns in the South have been as strong at the state level. Cox, a University of North Carolina historian, obviously knows better and must be aware of (1) the inconvenient truth that Democrats have had considerable governing responsibility during the South’s recent history and (2) the decidedly un-progressive ways Southern Democrats have used their powers.

The fact is that those perennial challenges have been managed less by conservative Republicans, and more by Southern Democrats, who until the last few election cycles, still dominated state legislatures and held their share of governorships—trends with which many national observers are unfamiliar, as they erroneously assume that the deep red presidential voting patterns in the South have been as strong at the state level. Cox, a University of North Carolina historian, obviously knows better and must be aware of (1) the inconvenient truth that Democrats have had considerable governing responsibility during the South’s recent history and (2) the decidedly un-progressive ways Southern Democrats have used their powers.

At least one assumes she is. Does Cox actually understand that in Alabama, Democrats have only sporadically embraced reforming a state constitution that perpetuates one of the most sharply regressive tax structures in the nation, or that the state’s Democratic Party is funded primarily by a gambling lobby that enriches itself on the backs of the low wage poor? Would it be bothersome to Cox that the same gambling interests lavished huge campaign sums on an initiative to monopolize the state’s casinos in the hands of a couple of magnates, inside a few counties that are almost entirely black and impoverished? What about the effort the state Democratic Party spent trying to block an ethics package aimed at reducing lobbyist influence in state politics, the kind of good government crusade progressives salivate about at the national level?

To a depressing degree, the same elements that have warped Alabama’s Democratic Party into a weirdly retrograde force, at least on local issues, are equally present with their regional co-partisans—they include a faux populist aversion to elite supported reforms, an obsession with racial patronage politics, and a persistent trouble with raising money that leads to a few convenient if corrupting alliances.

The point is not that Republicans are blameless in the South’s long running stagnation, or that they have shown much wherewithal to address the region’s simmering economic inequality or its oligarchical political remnants. But any fair accounting of the South’s woes has to lay some blame at not just ideological descendants of Jesse Helms and Strom Thurmond, or dead Dixiecrats, but racially tolerant, nationally liberal Southern Democrats who have made their peace with the South’s backwardness.

In fact, in many cases, they have actively aided and abetted that backwardness. The most distressed counties in Alabama’s Black Belt and Mississippi’s Delta remain that way partly because of an anti-business tort culture that was sustained in turn by one of the Democratic Party’s most generous financiers, the trial lawyer lobby. A decade ago, while they were still winning elections, Democratic governors did their share to deplete university budgets (usually at the bidding of teacher unions trying to protect K-12 teacher’s salaries) and in some instances they camouflaged their maneuvers with anti-elitist barbs that would shame any move in Sarah Palin’s playbook.

Cox deserves credit for her pointed criticisms of the national Democratic Party’s neglect of the South outside of Virginia and North Carolina, and for a theory of voting trends that flawed as it is, at least does not rest exclusively on intimations of white racism. And she is right that a more Democratic South would be less theocratic, not as inclined to embrace birther myths around Barack Obama, and less tempted to bash Mexican immigrants. But would a more Democratic South do much better at rooting out the economic deprivations, and the entrenched special interests that have straight-jacketed innovation? To a degree it takes a native Southerner to appreciate, the answer is much more conflicted than Cox or many national liberals assume.

Leave a Reply