Today — as on every April 4 — as the nation commemorates the anniversary of one of the worst days in our history; as some of us celebrate the anniversary of the greatest speech of the 20th Century; my mind is on my father. And my memory focuses on a winter day in the mid 1970s, sitting shotgun in his tiny, tinny, navy blue Pinto.

I can still remember my father’s smile that day.

He didn’t smile that often. His usual expression was somber, serious—squinting toward some imperceptible horizon. He was famously perpetually lost in thought: an all-consuming inner debate, an hourly wrestling match between intellect and emotion. When he did occasion a smile, it was almost always of the taut, pursed “Nice to see you” variety.

But on occasion, his lips would part wide, his green eyes would dance in an energetic mix of chutzpah and child-like glee. Usually, it was because of something my sister or I had said or done.

But this day, this was a smile of self-contented pride. Through the smoky haze of my breath floating in the cold, dense air, I could see my father beaming from the driver’s seat, pointing at the AM radio, whispering words of deep satisfaction with a slow and steady nod of his head and that unfamiliar wide-open smile: “That’s my line…Yep, I wrote that one too…They’re using all my best ones.”

He preempted my typically hyper-curious question-and-answer session with a way-out-of-character boast: The new mayor had asked him—my dad!—to help pen his first, inaugural address. And my hero had drafted all of the lines that the radio was replaying.

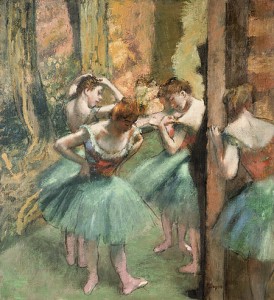

This was about the time when our father-son chats had drifted from the Reds and the Wildcats to politics and doing what was right. My dad was never going to run for office. Perhaps he knew that a liberal Jew couldn’t get elected dogcatcher in 1970s Kentucky. But I think it was more because he was less interested in the performance of politics than in its preparation. Just as Degas focused on his dancers before and after they went on stage—the stretching, the yawning, the meditation—my father loved to study, and better yet, help prepare, the ingredients of a masterful political oration: A fistful of prose; a pinch of poetry; a smidgen of hyperbole; a dollop of humor; a dash of grace. When properly mixed, such words could propel a campaign, lance an enemy, or best yet, inspire a public to wrest itself from apathetic lethargy and change the world.

This was about the time when our father-son chats had drifted from the Reds and the Wildcats to politics and doing what was right. My dad was never going to run for office. Perhaps he knew that a liberal Jew couldn’t get elected dogcatcher in 1970s Kentucky. But I think it was more because he was less interested in the performance of politics than in its preparation. Just as Degas focused on his dancers before and after they went on stage—the stretching, the yawning, the meditation—my father loved to study, and better yet, help prepare, the ingredients of a masterful political oration: A fistful of prose; a pinch of poetry; a smidgen of hyperbole; a dollop of humor; a dash of grace. When properly mixed, such words could propel a campaign, lance an enemy, or best yet, inspire a public to wrest itself from apathetic lethargy and change the world.

Now, for the first time, I realized that my father was in the middle of the action. And I was so damn proud.

– – –

My dad’s passion for words struck me most clearly when I prepared his eulogy. For the past two years of his illness, I’d finally become acquainted with the real Robert Miller, stripped down of the mythology, taken off my childhood pedestal. And I was able to love the real human being more genuinely than ever before. The eulogy would be my final payment in return for his decades of one-sided devotion: Using the craft he had lovingly and laboriously helped me develop, I would weave prose and poetry, the Bible and Shakespeare, anecdotes and memories, to honor my fallen hero. In his final weeks of consciousness, he turned down my offer to share the speech with him. I will never know whether that was due to his refusal to acknowledge the inevitable, or his final act of passing the torch: The student was now the author.

While the final draft reflected many varied influences, ranging from the Rabbis to the Boss (Springsteen), the words were my own. Except for one passage in which I quoted my father’s favorite memorial tribute: read by Senator Edward Kennedy at his brother, Robert’s funeral:

My brother need not be idealized, or enlarged in death beyond what he was in life, to be remembered simply as a good and decent man, who saw wrong and tried to right it, saw suffering and tried to heal it, saw war and tried to stop it.

– – –

Now as Lloyd Bentsen might have said, Robert Miller was no Robert Kennedy.

Indeed, Bobby Kennedy was my hero’s hero. In my dad’s study hung a letter from Bobby as part of a visual tribute to the holy trinity of liberal boomer martyrdom: RFK, JFK, and MLK, all three enlarged in death with the same childlike reverence and wonder usually reserved for a father by a young son.

But Bobby was my father’s favorite, probably because he could identify with him the most. John Kennedy had the glamour and charisma. Martin Luther King, Jr., the courage and the vision. Bobby—always, to my dad and many others like him, it was tellingly “Bobby,” not “Robert” or “Bob”—was shy and awkward; slight and child-like; temperamental and blunt; inelegant in appearance and limited in oratory. But there was such power in his words, particularly during the last years of his life when he emerged as the Bobby Kennedy that we all think of today. Words that mixed hope and desperation, frustration and inspiration. Words that could have helped heal a bitterly divided nation.

And it was a nation that desperately needed healing. If 1967 had the Summer of Love, 1968 brought America the Season of Hate. The anti-Vietnam cauldron was bubbling over, stoked by the heat of the Tet Offensive and the unprecedented prime-time scalding by America’s Most Trusted Man, Walter Cronkite. The civil rights movement had arrived at a bleaker and angrier phase, punctuated by waves of racial violence in urban areas across the country. And of course, the assassinations of King and Kennedy ushered in one of the darkest, most anxious periods in the nation’s history.

For unrepentant dreamers like my father, Bobby Kennedy had offered a ray of hope during his ill-fated presidential campaign. In marked contrast to his contemporaries—many of whom had added fuel to the national fire through their demagogic recriminations; seeking political multiplication through societal division—Bobby aimed his vision at our better angels, trying to bring Americans together, reinforcing the moral imperative to love our neighbors, particularly those who represented the least of us. Kennedy spoke not to an imaginary silent majority, but on behalf of the all-too-real invisible masses—the distressed, the disaffected, the disenfranchised, the disempowered—from coal miners in Appalachia, to fatherless boys in Bedford Stuyvesant, to migrant workers in California. In speech after speech, he lashed out at political selfishness, societal aggression, and moral parsimony, as he struggled to stitch together a diverse patchwork of Americans desperately reaching out for someone to lift them up.

Perhaps because of his celebrity, perhaps because his campaign was declared DOA by the experts, perhaps because the establishment was against him, perhaps because the all-too-premature death of his brother convinced him that life was too short—whatever the reason—Bobby spoke in a way that no past or future political consultant would ever advise: candidly and straight from the heart. And in so doing, his words touched the hearts of thousands of Bob Millers, into perpetuity.

Of course, the words of JFK and King are far more famous. Each man had his defining moment, on crystal clear blue sky days, on opposite sides of the nation’s public square. The Capitol served as backdrop for President Kennedy’s inspirational inaugural call for national service and global freedom. The Great Emancipator’s shadow provided spiritual comfort for Dr. King’s dream-weaving plea for equality.

Bobby’s greatest moment had none of the same trappings of glory and history. But the context, the content, and the consequence are all the stuff of goose bump-inducing legend.

It was 43 years ago today, April 4, 1968, and a bitter, black nightfall had descended on one of our nation’s grayest days. Robert Kennedy stood on the back of a truck in a vacant lot, surrounded by dilapidated public housing units, in the heart of the Indianapolis ghetto. His hair tussled, wearing his brother’s old overcoat, Bobby stepped up to a single microphone before a growingly angry African-American audience that had waited hours in the freezing cold to confirm what many had already heard: that King—their Voice—had been permanently silenced. And without notes, speaking directly from his heart, a heart that ached from an unimaginable half-decade of grief—grief for a brother, for a comrade-in-peace, for a nation in turmoil—Robert Kennedy improvised the speech of his life.

The speech’s impact is well known: While riots plagued, burned and ravaged 110 American cities that evening, Indianapolis remained calmed by a sober peace. But too many Americans have never heard the message.

His most famous line, reminding the angry audience that his brother too had been felled by a white man’s bullet, were words that only he could have delivered. And only RFK, who had sought the refuge of Greek poetry to cope with his personal grief, would have quoted these same poets in the middle of what would have been a political rally.

But at the core of the speech, you can find universal language: words that could apply to any generation; words that have impact still today:

What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness, but is love, and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black…We can do well in this country. We will have difficult times. We’ve had difficult times in the past, but we — and we will have difficult times in the future. It is not the end of violence; it is not the end of lawlessness; and it’s not the end of disorder. But the vast majority of white people and the vast majority of black people in this country want to live together, want to improve the quality of our life, and want justice for all human beings that abide in our land.

As he had done throughout that magical 1968 campaign, Kennedy took the opportunity not simply to pacify the immediate audience, but to share his communitarian message with all Americans. A divisive selfishness had emerged in the late 1960s that began to dominate the body politic. Kennedy drew upon Greek ideals and Judeo-Christian principles, reminding Americans that the only way that our nation could flourish was through pursuit of a common good. Sure, there would always be outliers and extremists who provoked dissension and divisiveness to strengthen their own selfish hands. But the vast majority of Americans want us to put aside our labels on occasion, to love our neighbors as ourselves, to reach for a common higher ground. On one of the darkest evenings in American history, RFK reminded us of our potential for greatness, if only we ignored the haters and remembered the Golden Rule.

It’s been more than forty years since hope appeared to have taken its final breaths on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel and in the kitchen pantry of the Ambassador Hotel. More than forty years of wandering: through the deserts of Iraq and the jungles of Vietnam; through Watergate and Iran-Contra and impeachment; through partisanship and polarization and powerlessness and pusillanimity. More than forty years dominated by a politics of self-interest, an involuntary conspiracy among the politicians, industry chieftains, culture vultures, and the media, all battling each other to wrest out their own fleeting piece of power, fifteen minutes of celebrity, or pound of fool’s gold.

For the briefest time, it appeared as if those four decades had led us, like the wandering Jews of the Sinai, to the border of a new kind of Promised Land. It actually seemed possible that the paralyzing politics-as-usual could be defeated and replaced by a resolute communitarian focus on working together and marching forward to solve the nation’s perpetual and perplexing problems. It appeared as if America—finally—might just have truly entered a post-racial, post-partisan era.

The promise was accompanied by a powerful symbol of a revolutionary reality: Just as Bobby Kennedy had famously predicted, an African-American had risen to the same seat of power held by his brother. In the hopes of many, Barack Obama was the putative Joshua, the logical successor—and a messenger with a similar message—to his spiritual Mosaic predecessors, King and the Kennedys. Obama had lifted himself to the highest political heights through the power of his own heart-inspired words—from his majestic keynote address at the 2004 Democratic convention to his two popular and critically acclaimed self-penned memoirs. Then his rhetorical skills helped him weather the storms of a bitter national campaign and a taxing first few months in office, a time of tremendous economic dislocation and two simultaneous, unpopular wars.

The promise was accompanied by a powerful symbol of a revolutionary reality: Just as Bobby Kennedy had famously predicted, an African-American had risen to the same seat of power held by his brother. In the hopes of many, Barack Obama was the putative Joshua, the logical successor—and a messenger with a similar message—to his spiritual Mosaic predecessors, King and the Kennedys. Obama had lifted himself to the highest political heights through the power of his own heart-inspired words—from his majestic keynote address at the 2004 Democratic convention to his two popular and critically acclaimed self-penned memoirs. Then his rhetorical skills helped him weather the storms of a bitter national campaign and a taxing first few months in office, a time of tremendous economic dislocation and two simultaneous, unpopular wars.

Alas, as the heat and humidity of August returned to the swamp of our nation’s capital, the American Dream morphed back into the Impossible Dream, and we had strayed into a new Summer of Hate. From the radio blowhards to the cable news agitators to the “town hall” bullies to the craven “leaders” hiding behind their Twitters or State of the Union heckles, the language of hate reemerged with a passion. The destructive power of misused words reared its ugly head, as deliberately disingenuous epithets such as “death panels” and “socialists” and “terrorists” poisoned the political marketplace. And the President who ran sincerely as a uniting figure, suddenly was typecast by a small, but extraordinarily vocal and venal minority as the most polarizing figure in recent history—since his immediate predecessor, of course. Even after the torch was figuratively and semi-officially passed at Camelot’s final funeral (at which Obama eulogized the brother who had eulogized Bobby), his powerful message of healing and unity seemed to appear, in retrospect, to be naïve and unattainable.

But all is far from lost. There is a pathway we can follow, and the foundation was laid by Bobby Kennedy’s words that tragic day in Indianapolis. It’s a message, too, that cannot—indeed, it must not—be limited to politicians and their narrow sphere of influence. Rather, it belongs to every American who recognizes that words really do matter: those of us who are moved by a thoughtful sermon or an inspiring debate; lifted by a well-crafted stanza or a well-honed lyric; animated by a richly-textured crossword puzzle or a hyper-competitive Scrabble game; and most of all, inspired and excited and driven by the challenge of finding the right word—that perfect word—to win an argument, conclude a brief, rhyme a verse, soothe a friend, direct a child, motivate an audience, or even win over a heart. It’s for attorneys and preachers; poets and musicians and screenwriters; agitators, healers, lovers and fighters.

Can we use our words to heal, instead of to divide? Can we follow RFK’s example by meeting hateful oratory with offers of compassion? Can we hold onto our strongest beliefs, while, on occasion, toss aside our labels to work for the common good?

This Web site is another tribute to my father and my father’s hero. In a very small way, I’m hopeful we can begin the kind of civil dialogue that Bobby Kennedy was never able to finish. We all are RFK’s legacy; it is our obligation to live out his vision.

For you don’t have to be a Kennedy to leave this world a better place. As Robert Miller proved, you simply need to share your words—and your passion—with your friends, neighbors, and most of all, the people you love.

Leave a Reply