In 1963, William F. Buckley, Jr. quipped “I would rather be governed by the first 2000 names in the Boston phone book than the faculty of Harvard University.” The quote has been passed around so often in various forms (my initial Google search this morning returned more than seventy million hits), with and without attribution to the late Mr. Buckley, that the original context of the comment (a jab at the Kennedy brain trust) is lost in the mist.

In 1963, William F. Buckley, Jr. quipped “I would rather be governed by the first 2000 names in the Boston phone book than the faculty of Harvard University.” The quote has been passed around so often in various forms (my initial Google search this morning returned more than seventy million hits), with and without attribution to the late Mr. Buckley, that the original context of the comment (a jab at the Kennedy brain trust) is lost in the mist.

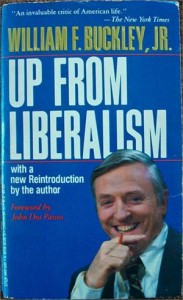

At the risk of alienating many of my readers, I will declare right now that Buckley has been one of my heroes since my teenage years. However my opinions on specific issues may have diverged from his over time, Buckley’s sparkling wit and clarity of thought continue to inspire me. I still read his works for pleasure, and measure my own poor writing style against his.

Even the cleverest comments from great thinkers, however, can be dangerous when they are wrenched from their original context and take on a life of their own. (Thomas Jefferson, the tree of liberty, and the blood of tyrants come to mind…) Buckley’s Boston phone book quote is just such a comment. It has become a popular rhetorical tic among conservatives, and threatens to be more damaging to the conservative intellectual project than anything ever dreamt up on the left.

Even the cleverest comments from great thinkers, however, can be dangerous when they are wrenched from their original context and take on a life of their own. (Thomas Jefferson, the tree of liberty, and the blood of tyrants come to mind…) Buckley’s Boston phone book quote is just such a comment. It has become a popular rhetorical tic among conservatives, and threatens to be more damaging to the conservative intellectual project than anything ever dreamt up on the left.

The quote, and the attitude behind it, has been in a great deal of conscious and unconscious circulation of late, as Republican presidential candidates attempt to contrast themselves with President Obama and to deal with their own occasional lapses of knowledge or eloquence. Thus we have Rick Perry, fresh off recent debate catastrophes, saying to all who would listen, “I am a doer, not a talker. ” Similarly, Herman Cain, far from embarrassed about his lack of facility in discussing complicated international events, has embraced ignorance, proclaiming (in unconscious echo of a classic moment from The Simpsons): “We need a leader, not a reader.” In this time of crisis, these messages suggest, the country should reject intellectual attainment in favor of someone unfettered by too much thinking.

What is going on here? The recent comments from Perry and Cain, as well as earlier dustups around the general knowledge of candidates such as Sarah Palin or Michelle Bachman, are the culmination of a decades-long process, going back past George W. Bush to Ronald Reagan all the way to Dwight Eisenhower. Frustrated by the real and perceived condescension of liberal intellectuals toward their leaders and conservative positions generally, conservative politicians and opinion leaders have surrendered to the populist temptation. Rather than defending themselves on an intellectual level, they are conceding the point, embracing anti-intellectualism and attempting to claim that a lack of intellectual sophistication is proof of superior integrity and honesty.

What is going on here? The recent comments from Perry and Cain, as well as earlier dustups around the general knowledge of candidates such as Sarah Palin or Michelle Bachman, are the culmination of a decades-long process, going back past George W. Bush to Ronald Reagan all the way to Dwight Eisenhower. Frustrated by the real and perceived condescension of liberal intellectuals toward their leaders and conservative positions generally, conservative politicians and opinion leaders have surrendered to the populist temptation. Rather than defending themselves on an intellectual level, they are conceding the point, embracing anti-intellectualism and attempting to claim that a lack of intellectual sophistication is proof of superior integrity and honesty.

Now, a humble appreciation of one’s own limitations is not a bad thing at all. Indeed, it may be more appealing than the occasionally prickly and admonitory demeanor that Newt Gingrich, for example, has displayed in recent debates when he spent more time challenging questions than answering them. It is also certainly true that being President requires skills at managing people and presenting issues that go beyond traditional measures of intelligence. Herman Cain has a point when he says that the President need not know every detail as long as he has advisers who do. Nevertheless, no sensible person would deny that it would be a big help in making key decisions if the President were committed to knowing as much as possible about things, rather than dismissing the effort of knowing as somehow beneath his managerial dignity.

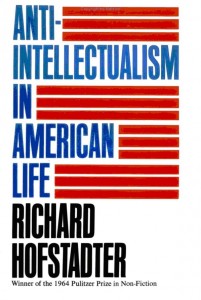

American mythology has always celebrated the simple virtues of the common man, and bred a suspicion of intellectuals as inauthentic, scheming, or dangerous. Richard Hofstadter won the 1964 Pulitzer Prize for his analysis of the roots of this attitude in a classic work, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, that still rewards reading. One can certainly appreciate the emphasis on authenticity and should also remember that the Left has been just as willing to embrace notions of common man authenticity as the Right, depending on the context. American society has always had a strong egalitarian streak, which leads to a discomfort with and distrust of experts, and thus feeds the popularity of epigrams such as Mr. Buckley’s.

But we need to distinguish between metaphor and a reality, and not allow ourselves to be entranced by what is just an artful turn of phrase. All praise of the common man aside, there are very good reasons to prefer leaders who are driven by intellectual curiosity, who have taken the time and effort to study contemporary problems and are thus best able to decide between the options presented by advisers. I can think of few Americans who would, say, entrust the health care of their loved ones, the construction of their homes, or even the mechanical health of their car, to someone who proclaimed that he operated based purely on common sense rather than learning and experience. Why, then, would we want to entrust the leadership of the country to someone who does not bother to keep up with current events, or even to study his own talking points?

The truth is, we do not, and even those who pretend otherwise know better. The worst thing about this populist anti-intellectualism is that it is phony. Herman Cain did not rise in the business world by disdaining the study of the details of his business, and Rick Perry devotes great effort to presenting himself when it matters (as in the ad cited above, where he smoothly reads from a teleprompter his lines about how he is not the kind of guy who can smoothly read from a teleprompter). Instead of owning up to their own failures of preparation, Cain and Perry are hoping to play on the public’s own insecurities and anti-intellectual reflexes as a smokescreen to distract from their own stumbles. Such an obvious tactic is bogus and insulting, and no one should stand for it.

It would be a disservice to Buckley’s legacy for conservatives to take from his Boston phone book comment the lesson that the proper response to claims that conservatives are ignorant is a pugnacious, “Yeah, what’s it to ya?” For I rather doubt that Mr. Buckley (Yale class of 1950, member of the famously élite Skull and Bones, and famous for his mastery of five-dollar words) ever was a worthy avatar of the common man. Nor do I believe that Buckley’s statement was intended to deride the importance of education or of expert knowledge. Rather, Buckley’s entire career aimed to remind educated liberals that conservatives could be educated too. A personal favorite quote of mine is: “Though liberals do a great deal of talking about hearing other points of view, it sometimes shocks them to learn that there are other points of view.”

That sentiment, taken from Buckley’s 1959 classic Up From Liberalism, emphasizes that political debate should take place on the basis of ideas and argument and in an atmosphere of genuine intellectual curiosity. It is so tempting to assume that others only disagree with us because they are either too stupid to know better or too evil to care. It is tempting, and self-aggrandizing, and deeply misguided. And it is just as wrong to assume that one’s own positions are somehow exempt from intellectual scrutiny because they are more authentic. Serious debate can only take place when each side is well prepared both to present its own case and analyze that of the other side. Honest conservatives should not shrink from serious debate, nor should they hide behind phony anti-intellectualism.

Ignorance on its own is no vice; it is a natural condition of life. Each of us is ignorant about many things. Nevertheless, ignorance on its own is also no virtue. Awareness of one’s own ignorance should inspire humility, and an eagerness to learn more. If ignorance does not inspire curiosity, however, then it is indeed a vice. Arrogant ignorance, which flaunts lack of knowledge—or worse, tries to present ignorance as superior to knowledge—is the worst vice of all. Such an attitude actively devalues knowledge. It encourages a stubborn blindness to opposing viewpoints that is deeply dangerous for the future of any state in such a complicated world. As Buckley himself wrote in 1955, in the initial Publisher’s Statement for his new magazine National Review: “Our political economy and our high-energy industry run on large, general principles, on ideas — not by day-to-day guess work, expedients and improvisations.” Anyone who aspires to be the CEO of this nation should keep that in mind. And so should those who are responsible for selecting that CEO.

Leave a Reply