One year ago, I arrived in the small town of Manchester, Kentucky, a scenic spot tucked deep in an Appalachian mountain hollow, where I would be spending most of 2010. Before I was shown my new digs, the staff processed me. That meant going repeatedly through the standard battery of questions. The third questioner finished and sent me to a heavyset woman.

“Height and weight?” she asked.

“5’6”, 120.”

She examined my slight frame and frowned. “Education level?”

I winced. “Ph.D.”

She shot me a skeptical look. “Last profession?”

“State Senator.”

She rolled her eyes. “Well, I’ll put it down if you want. If you wanna play games, play games. We got ones who think they’re Jesus Christ, too.”

She then sent me to the counselor, a small sandy-haired man wearing a light blue polo shirt and a wispy mustache. He flipped through the pre-sentencing report, pausing briefly to absorb the summary of the case, and shook his head. “This is crazy,” he said quietly, without looking at me. “You shouldn’t be here. Waste of time. Money. Space.”

A guard approached and escorted me to a bathroom without a door. Then another guard appeared. Gruff and morbidly obese, he spoke in a thick Kentucky drawl. “Stree-ip,” he commanded. I stripped.

“Tern’round,” he barked. I turned around.

“Open up yer prison wallet,” he ordered.

I looked at him quizzically.

“Tern’round and open yer butt cheeks.”

I complied.

“Alright, you’s good to go.” he said.

I wasn’t Senator Smith anymore, or Professor Smith. I was #36607-044.

******

Click here to read Jeff Smith’s stunning expose on sex, lies and prison: “When J.T. Met Porkchop”

Exactly six months earlier, I’d bounded onto the elevator up to my lawyer’s office, nodding at a familiar-looking man in a gray suit. Like most politicians, I had a uniform. Blue shirt, sleeves rolled-up, yellow tie, slim-fitting khakis, wavy, longish hair: the picture of a young, energetic state senator with what many observers deemed a bright future on a larger stage. I was coming off a successful legislative session in which I’d filibustered a major bill for weeks before reaching a compromise in the wee hours of the final day that gave me 90% of what I wanted – the protection of tax credits that helped revitalize inner-city St. Louis. I’d sponsored and passed two bills that reformed our state’s child support laws, one which helped men struggling to pay child support avoid crippling felony convictions and instead be diverted to a special “fathering court” where they could receive job training and the support to get back on their feet. I was finally starting to figure out how the Capitol really worked – and how to make the system work for my constituents.

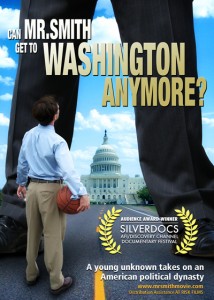

Three years before, a filmmaker had made an award-winning film chronicling my near-miss, youth-powered, long-shot congressional campaign titled “Can Mr. Smith Get to Washington Anymore?”,which was short-listed for an Oscar. And sure enough, as I watched the lights on the buttons flash in the elevator up to my lawyer’s office, the nondescript guy in the gray suit asked, “So, you gonna run for Congress again, Mr. Smith? Or City Hall?”

Three years before, a filmmaker had made an award-winning film chronicling my near-miss, youth-powered, long-shot congressional campaign titled “Can Mr. Smith Get to Washington Anymore?”,which was short-listed for an Oscar. And sure enough, as I watched the lights on the buttons flash in the elevator up to my lawyer’s office, the nondescript guy in the gray suit asked, “So, you gonna run for Congress again, Mr. Smith? Or City Hall?”

When I got back onto the elevator an hour later, the spring in my step was gone. My lawyer had informed me that a) my political career was over, b) my best friend and closest ally had been taping our private conversations for months, c) the contents of these tapes would be splashed across the front page of the newspaper for weeks on end, and d) I was probably going to jail.

******

When I arrived at my unit, I was the only white person, which immediately made me a source of curiosity.

“White-collar?” one guy asked.

“Yup.”

“What you done did?”

“Lied to the feds.”

“Damn, how they know?” asked another.

“One of my best friends was wired.”

A chorus of “Punk-ass motherfucker!”s rained down.

Then somebody said, “Dude need to get chalked.” That was slang, I realized, describing a body at a crime scene.

The chorus went “Hmm-hmmmmm!”

I soon learned that it was taboo to ask someone why they were locked up, as it was occasionally a sore subject. (Apparently the fact that I was 5’6” and 120 pounds upon arrival mitigated my cell block’s apprehension about asking me immediately.) I did learn that all the guys in the unit at that point were high school dropouts. However, they knew more about criminal law than most of my former colleagues in the state Senate.

They were mostly drug dealers who got caught with enough crack to receive a mandatory minimum sentence and began 5-20 year bids at medium- or high-security institutions before transferring to lower security levels and ultimately reaching the Promised Land of the federal prison system, the minimum-security prison. Even after a decade or more without Internet access, they avidly followed pending legislation that could ameliorate their situations. Most had memorized not only the relationship between crimes and their corresponding offense levels according to federal guidelines (along with the additional point values of various “enhancements” sought by prosecutors), but had also memorized the exact range of months for each offense level.

Of course, not all the prisoners were angels. My cellie had been in and out of prison for 25 years. When the conversation turned to taxes, he gazed out the window. “Shit, I been locked up so long I don’t know when the last time was I filed taxes,” he said wistfully. “They don’t give you no muthafuckin W-2 when you slingin’ dope.”

******

I thought of this the other day when I started work on my taxes. Life’s a little different these days than it was the last time I did my taxes. For starters, I didn’t have much income in 2010, just a few thousand bucks in the year’s final months after I came home from some free-lance research and writing. I’m finishing a manuscript, but my agent hasn’t sold it to a publisher yet. I helped write the electoral analysis piece of St. Louis’s bid for the Democratic National Convention, but we didn’t get picked, so I didn’t get paid. I’m interviewing for a couple professorships, but no offers yet. I have a few private sector offers, but I’m not passionate about selling products or services or anything, really, except ideas. I was asked to be a regular guest on a morning show for a talk radio station, but they were reluctant to pay – and with a new wife and a kid on the way, I can’t work for free right now. Board members at area nonprofits have asked me to apply for their executive director openings, but they have formal processes, and formal processes don’t bode well for felons.

So while I figure the long-term stuff out, I’m consulting for a statewide group that promotes affordable housing, helping direct their legislative and membership engagement strategies, and about to begin similar work for another group. It’s good for now – intellectually stimulating, politically relevant, and well-compensated, compared to what I was making a year ago at this time.

And now, I am trying to oblige my friend Jonathan Miller, who gave me 1500 words to explain where I am…when I don’t know exactly where that is myself. What I do know is that I have a personal assistant provided by http://TheRecoveringPolitician.com, a bright and witty UK grad named Robert who edits my work and helps on the tech side. Yes, that’s where I am: a self-employed felon with an intern at my disposal, the veritable CEO of Kramerica.

But enough pathos. I had a tax question: do I include my prison wages as income?

The prison Captain, who served as the warden’s chief disciplinarian, had confronted me a few days after my arrival, claiming that I’d broken prison rules by negotiating with a literary agent. The next day I got my work assignment: loading and unloading trucks in the prison warehouse from 7 a.m.-3 p.m each day. I started at $5.25/month before hard work and rising seniority helped me get a raise to $21.75/month. On my first day at work, the Captain sneered at me and laughed as he watched me jump out of the back of the truck. It was then that I realized my work assignment was no accident.

I worked with six other guys to haul the food that fed 2000+ people at the two prisons on the compound. Most days we moved 30-40,000 pounds of food into two warehouses and five huge industrial freezers, where we spent a few hours a day in -20 degree temperatures. Meat arrived in 20- to 80-pound boxes; rice, sugar, beans, and flour in 100-pound bags. Four of my colleagues were twice my weight; the other two nearly three times (310 and 350 pounds, respectively). But as sore as my back was most nights, I focused on the silver lining: when you come into prison at 120 pounds, it’s nice to be buddies with the biggest guys on the compound.

The long hours made for bonding, and it turned out that the guys needed a point guard for their basketball team in the prison league, which was the highlight of everyone’s week (especially the bookies). A lifetime of playing and coaching basketball had helped me survive in politics; my biggest event was a 3-on-3 tournament that I started in the city’s most violent neighborhood and attracted thousands of spirited but peaceful youths each year. Never did I imagine that basketball would let me build the friendships to help me survive in prison.

By most standards, my tax question was inconsequential: my cumulative pay for my eight months in prison was about $100. That said, the original offense leading to my predicament had also seemed relatively minor: I’d signed an affidavit falsely claiming ignorance of an anonymous postcard sent during a losing campaign five years earlier which highlighted an opponent’s poor attendance record. (In fact, I’d approved a staffer’s request to meet with the man who planned the mailer; the wiretaps caught me admitting as much, along with a few other choice comments.)

So no, $100 wasn’t much – hell, if Madoff ganked billions for decades without anyone catching on, and if Dick Fuld pillaged Lehman Brothers for a half billion before slinking out the back door, I could probably get away with not declaring $100 of prison wages.

But this time, I decided not to risk it.

———

Enjoy this post?

Check out the RP’s essay — “Why Barry Bonds Should NOT go to Jail” –in which he argues that Jeff Smith should NOT have been sentenced to serve time in a jail with violent offenders.

Also, read Jeff Smith’s follow-up piece about the lessons he learned during his jail sentence: “Learning Entreprenuership in Jail“

Also, check out these other terrific stories about recovery and redemption:

The RP’s “My Dad, RFK and the Greatest Speech of the 2oth Century”

John Y. Brown, III’s hilarious “What Do We Do Now?”

Leave a Reply