If Showtime’s exemplary “Homeland” is the new pace-setter for politically themed drama, and CBS’s “Good Wife” is a successful, if less psychologically rich, portrait of a scandal surviving heroine, what to make of Starz’s largely obscure “Boss”, an ensemble drama about a fictional Chicago Mayor who is fighting off mental illness and all manner of intrigue? It is a well-acted, intricately conceived narrative that has utterly failed to break through the popular consciousness, much less the Emmy circle, and it is worth pondering why its ambitions have gone unrealized at a time when political morality plays are newly resurgent on network and cable.

If Showtime’s exemplary “Homeland” is the new pace-setter for politically themed drama, and CBS’s “Good Wife” is a successful, if less psychologically rich, portrait of a scandal surviving heroine, what to make of Starz’s largely obscure “Boss”, an ensemble drama about a fictional Chicago Mayor who is fighting off mental illness and all manner of intrigue? It is a well-acted, intricately conceived narrative that has utterly failed to break through the popular consciousness, much less the Emmy circle, and it is worth pondering why its ambitions have gone unrealized at a time when political morality plays are newly resurgent on network and cable.

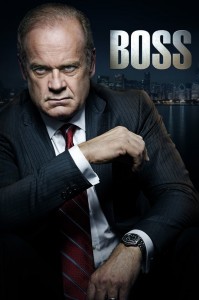

The rap on “Boss” may well be that the conceit at the heart of the show—that gaining and holding power is one sordid, muddy blend of egos and ruthlessness—is so shopworn that it manages to bore. The protagonist, the 20 years plus mayor of the Windy City, Tom Kane (Kelsey Grammer) is a brute: by the middle of the second season, we know that his power is built on a web of corrupt bargains with city developers, a sham of a marriage to the glamorous daughter of his predecessor, and a staff of devotees who protect his lies out of some alchemy of ambition and loyalty. We know he ruins and takes lives. Nothing new here: it is more or less an amped up version of every recycled stereotype about the unseemly nature of power. Nor is there any justifiable thread for Kane’s abuses beyond the old stand-by—at least the city works for its elite, and the trains run on time, and the poor and the marginal are subsidized by a mixture of patronage and spoils. It is no accident that Chicago looks in this rendition less like a modern metropolis than a hulk of decaying deals and faded urban monuments.

The rap on “Boss” may well be that the conceit at the heart of the show—that gaining and holding power is one sordid, muddy blend of egos and ruthlessness—is so shopworn that it manages to bore. The protagonist, the 20 years plus mayor of the Windy City, Tom Kane (Kelsey Grammer) is a brute: by the middle of the second season, we know that his power is built on a web of corrupt bargains with city developers, a sham of a marriage to the glamorous daughter of his predecessor, and a staff of devotees who protect his lies out of some alchemy of ambition and loyalty. We know he ruins and takes lives. Nothing new here: it is more or less an amped up version of every recycled stereotype about the unseemly nature of power. Nor is there any justifiable thread for Kane’s abuses beyond the old stand-by—at least the city works for its elite, and the trains run on time, and the poor and the marginal are subsidized by a mixture of patronage and spoils. It is no accident that Chicago looks in this rendition less like a modern metropolis than a hulk of decaying deals and faded urban monuments.

True to its form, there are few sympathetic characters in this narrative: the city’s First Lady Meredith Kane (Connie Nielsen) is an autocrat in her own right who was complicit in the estrangement of their drug addicted daughter; the Mayor’s top aides in season One (Martin Donovan as Ezra Stone and Kathleen Robertson as Kitty O’Neill) are amoral connivers who mimic Kane’s viciousness until they become expendable too; State Treasurer Ben Zajac (Jeff Hephner) the young Democratic gubernatorial candidate who is a puppet of Kane, is simultaneously callow, lecherous, disloyal, and vacant. Kane’s rivals on the City Council operate out of the same shallow moral vacuum as Kane.

The sole redeeming figures to date are the African American chief of staff in Season 2, Mona Fredericks (Sanaa Latham) who agrees to enter Kane’s orbit to resurrect a dying inner city development but whose presumed flaw is her weakness for sacrificing means for ends, and Sam Miller (Troy Garity) the relentless city editor who is bent on exposing Kane’s venality but whose motives are clouded by his own career advancement and a hopelessly conflicted connection to the aforementioned Kitty O’Neill.

One imagines that there is a deliberateness in the fact that virtually every sexual relationship in this drama has rot at its core: from the alliance of the two manipulators who are the First Couple; to the drug addled Romeo and Juliet bond between Kane’s daughter and her supplier/boyfriend; to Jack Zajac’s bedding of anything appealing (or available) that crosses his sight line; to the readiness of several characters to deploy sex as a bargaining chip or gratuity. This is cable, so there is plenty of sex, but it is rarely even erotic, and typically is either a semi-violent act of dominance, or a twisted submission.

And all of this degradation and treachery is Boss’s missed opportunity: there is nothing to root for and nothing to trust in this hypothetical Chicago. What “Boss” has to say about contemporary urban politics is pedestrian and clichéd and its larger ruminations about power are more the cardboard of comic book stock than Machiavelli. It is not that the show is without any realism or flair: for all of its sometimes cheap symbolism—Kane’s illness causes hallucinations that are a proxy for metaphorical demons and a troubled conscience—the cast is far better than average, the dialogue brisk and Grammer gives Kane at his best a savage kind of willpower. But what “Boss”utterly fails to do is give its central characters the appeal of genuine moral conflict: they are almost all stunted and emotionally dead, cautionary tales more than anything else.

There is a grim kind of remorselessness in each episode of this show: the writers seem bent on extracting one more piece of deceit, one more back-stab, every week as if they had a grim duty to render their setting a little more depressing at every turn. But that kind of starkness is as much off-base as it would be to idealize its subjects. In omitting any complexity, the show is at its least recognizable: isn’t politics notable for being a blood-sport where all sides still have their own pretense to virtue, where the most cynical practitioner imagines he is righting some wrong, and doing some justice?

These kinds of shows have a growth arc: Shonda Rhimes’ “Scandal”got better once it shifted from the image crisis of the week to a sharper focus on a presidential affair that spirals in and out of control; “Homeland” set its course toward brilliance once it drew out Nicholas Brody and Carrie Mathison as damaged personalities. As “Boss” zips through its second season, it is improving in measured ways: the addition of Mona Fredericks and the slow temptation of Sam Miller are genuine ambiguities, if only for the suspense over whether either goes bad. The irony if the rebound is too late: that a show about the cynicism of political life was too cynical to survive.

(Cross-posted, with permission of the author, from OfficialArturDavis.com)

Leave a Reply