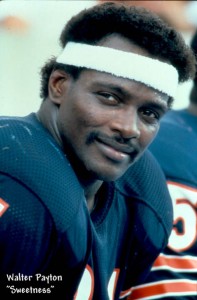

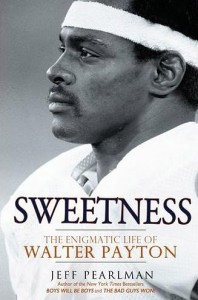

The last part is a true enough description of the largely impact free zone of the contemporary football star. The first observation, however, is flawed memory. It was not Simpson, for all his California glitter and celebrity, who was the last of a kind—it was a Mississippian who migrated north named Walter Payton. Jeff Pearlman, in his 2011 biography of the Chicago Bears Hall of Famer, “Sweetness”, reminds us that for about a decade, well beyond the normal career span of an NFL back, Walter Payton was the exemplary star who resonated well beyond his sport–especially if you were a Chicagoan eager for a hero in the aftermath of that city’s dismal decade of the seventies; an African American who relished the style of a charismatic HBCU grad effortlessly crossing racial barriers; or a lover of an underdog story who understood the depths in the South from which Payton ascended.

Even for Americans who only dimly knew the fine print of Payton’s athletic feats, he was the 80s sports celebrity who died too early and through no fault of his own, and his demise in 1999 from a rare liver cancer at 46 provoked tributes fit for the civic legend he had become.

“Sweetness” is a minutely researched, powerfully written narrative that gives the iconic side of Payton its due, but may be the most controversial sports biography of the past year. The football side of the account is not in dispute; to a degree not well remembered today, Payton was uncommonly good for an astonishingly long time. From 1976 to 1986, Payton amassed over 1200 yards each full season, topped the NFL record books for career rushing yards (and still ranks second, behind only Emmitt Smith), and at one point held the record for single game yards and consecutive 100 yard games. In a sport where the brutality of contact erodes skills quickly, Payton’s prolonged brilliance still arguably makes him the finest running back the NFL has produced.

It is the rest of Pearlman’s excavation that has provoked raw anger from old Payton associates. According to Pearlman, it is the character based side of the Payton legend that is in need of reexamination. If Pearlman’s sources are to be believed, Payton was as aggressively promiscuous as Tiger Woods; self-centered enough that he visibly pouted after a Super Bowl rout for his Bears because he failed to score an individual touchdown; and so ungrounded after football that he careened from one failed business venture to another, and even spiraled into pain-killer abuse.

It is the personal expose that is the most jarring, particularly if one is familiar with Payton’s skillfully manicured image. After all, it was Payton whose wife and children memorably appeared beside him at his press conference pleading for a liver donation, and who chose his 12 year old son to present him at his Hall of Fame induction ceremony. Pearlman alleges that the wife had been estranged for a decade and that Payton was wounded by her presence at his final press conference; that the same induction ceremony was marred by the proximity of Payton’s mistress a few feet away from where his wife was seated; and that the 1985 Chicago’s Father of the Year shunned a son he bore out of wedlock months before the award.

It is the personal expose that is the most jarring, particularly if one is familiar with Payton’s skillfully manicured image. After all, it was Payton whose wife and children memorably appeared beside him at his press conference pleading for a liver donation, and who chose his 12 year old son to present him at his Hall of Fame induction ceremony. Pearlman alleges that the wife had been estranged for a decade and that Payton was wounded by her presence at his final press conference; that the same induction ceremony was marred by the proximity of Payton’s mistress a few feet away from where his wife was seated; and that the 1985 Chicago’s Father of the Year shunned a son he bore out of wedlock months before the award.

A host of Payton’s cohorts have savaged the book as a combination of voyeurism and character assassination. To be sure, Pearlman has crossed the invisible line of sports journalism, which treads lightly on sexual revelations around athletes until those revelations somehow explode into public view: Tiger Woods’ exploits, for example, were open fodder for PGA tour gossip but did not see the light of day until an accident, a police report, and a media feeding frenzy “outed” him. Given the pristine quality of Payton’s reputation, and the absence of scandal during his life, Pearlman has done the dirty work of lifting up the details, and sorting out the reliable from the untrustworthy. He can’t possibly have every claim right. Not only is he dependent on the word of figures whose own accounts mark them as deceptive, or embittered, he is prey to another flaw of the character cop: once convinced of a subject’s moral perfidy, it is easy to credit every stray rumor.

But at the same time, the most slavish defender of Payton can’t deny that there is a volume of alleged misdeeds that also can’t all be untrue. The question, then, is how much of it is relevant in a biography about a dead man, not a politician cloaking himself in a “family values” guise. It’s a fiendishly difficult question. Pearlman’s thesis, that Payton regularly said one thing and lived and thought another, and built an image around values he didn’t hold, may be true, but is hardly atypical in Payton’s field or any other. To deserve the attention Pearlman gives it, there should be some linkage to Payton’s legacy as a football legend, which after all, is why we know his name and why a sportswriter is telling this story at all.

Pearlman falls short here—while he pokes a few chinks in Payton’s reputation for altruism and good works toward the disabled and the young, the good works are still there and Pearlman acknowledges that they genuinely enhanced the recipients. Certainly, Pearlman never sheds any doubt on the proper size of Payton’s legacy on the field; indeed, that side of Payton’s life looks larger as Pearlman recounts the second half of his career, when he excelled and outlasted peers like the forgotten George Rogers and Earl Campbell even as his raw ability diminished.

Pearlman falls short here—while he pokes a few chinks in Payton’s reputation for altruism and good works toward the disabled and the young, the good works are still there and Pearlman acknowledges that they genuinely enhanced the recipients. Certainly, Pearlman never sheds any doubt on the proper size of Payton’s legacy on the field; indeed, that side of Payton’s life looks larger as Pearlman recounts the second half of his career, when he excelled and outlasted peers like the forgotten George Rogers and Earl Campbell even as his raw ability diminished.

The best defense of Pearlman is that he reminds us that character is wrought with complexity. There are a few thoroughly unredeemed figures whose public and private existence is corrupt. There are the few legitimate saints who are worthy of emulation in every way. Neither describes most of us, nor the heroes we venerate. If this biography has a value beyond being a good weekend’s read, it might be to temper the adulation we reserve for our heroes. Since their cobwebs may just be hiding in the dark, we might do well to put our admiration several rungs lower. Better yet, we might honor them for the forgotten virtue of being sinners who knew how to keep getting up.

Leave a Reply