Harry Truman is the one president widely admired today who was generally reviled in his own times. There was no cult of personality around Truman while he was in the White House; to the contrary, he eventually logged the lowest approval ratings in Gallup’s history, just nudging out Richard Nixon on the eve of resignation. His legislative record was anemic. He failed to curb the anti-communist fervor known as McCarthyism, and the carnage of the Korean War is part of his resume.

Harry Truman is the one president widely admired today who was generally reviled in his own times. There was no cult of personality around Truman while he was in the White House; to the contrary, he eventually logged the lowest approval ratings in Gallup’s history, just nudging out Richard Nixon on the eve of resignation. His legislative record was anemic. He failed to curb the anti-communist fervor known as McCarthyism, and the carnage of the Korean War is part of his resume.

The fact Truman endures is a testament to two factors: the first, his exemplary decision to assert American leadership on behalf of democratic elements under siege, from Greece to Israel, denied the Soviet Union ownership of the second half of the 20th Century. Second, he won a campaign, improbably, heroically, and defiantly in the face of outlandish odds.

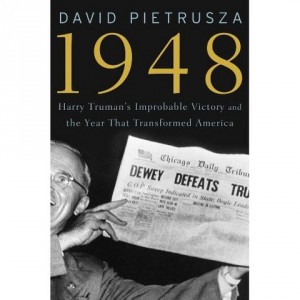

That second event is the subject of David Pietrusza’s latest presidential campaign history, “1948”, a worthy successor to “1920: The Year of the Six Presidents”, a superb recounting of a largely forgotten political season, and “1960: JFK v. LBJ v. Nixon”, which manages to shed fresh details on that year’s epic. Pietrusza opts for the brisk narrative/character sketch (think “The Making of the President”, but with no pretense of grandeur), over the minute retelling of every seminal event that weighs down Edmund Morris’ series on Teddy Roosevelt or John Milton Cooper’s well regarded 2008 biography of Woodrow Wilson. It is less grand history than a jaunty, essayist’s rendition—imminently readable and revealing.

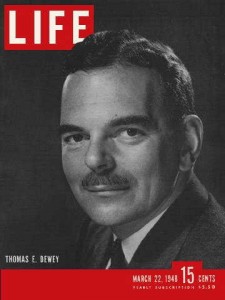

The best recalled aspect of “1948” is the seemingly helpless state Truman found himself in at the outset of the race: his Democratic Party was deeply split, with a sizable number of liberals regarding Truman as simultaneously too adventurous with his foreign policy and too feckless on the domestic side. The southern wing of the party was equally disgruntled, and a portion of it was intent on generating an electoral college deadlock that would make the preservation of segregation for another generation the ticket for a deal. The country seemed fatigued with Rooseveltian liberalism, and the Republican front-runner, New York Governor Tom Dewey, seemed inoffensive and competent enough to win easily.

As Pietrusza recalls, the tide shifted not on one monumental stroke, but on a series of gradual movements over the year. The left-wing challenge to Truman, in the form of a third party bid by the man he displaced as Vice President, Henry Wallace, dissipated due to Wallace’s ineptitude and his gullible tolerance of only thinly disguised communist sympathizers (as Pietrusza rigorously details, this is no J. Edgar Hoover or right-wing based smear: much of Wallace’s Progressive Party was a de facto communist column in an era when subversion of democracies was a genuine Soviet strategy). The “Dixiecrat” fourth party, led by Strom Thurmond, floundered in a way that their ancestors would have recognized—deep divisions over tactics and a deficit of plausible leaders.

As Pietrusza recalls, the tide shifted not on one monumental stroke, but on a series of gradual movements over the year. The left-wing challenge to Truman, in the form of a third party bid by the man he displaced as Vice President, Henry Wallace, dissipated due to Wallace’s ineptitude and his gullible tolerance of only thinly disguised communist sympathizers (as Pietrusza rigorously details, this is no J. Edgar Hoover or right-wing based smear: much of Wallace’s Progressive Party was a de facto communist column in an era when subversion of democracies was a genuine Soviet strategy). The “Dixiecrat” fourth party, led by Strom Thurmond, floundered in a way that their ancestors would have recognized—deep divisions over tactics and a deficit of plausible leaders.

It is the fall campaign where Pietrusza’s writing shines best, and where a subtle shifting of the public mood brings life back to Truman. We see Truman making the entirely controversial choice to dramatize the intransigence of congressional Republicans by hauling them back into session and daring them to pass his economic program (are you listening , David Plouffe?) Republicans taking the bait and refusing to give even nominal ground (are you listening, John Boehner?). Dewey, determined not to upset a public mood that he read as complacent, sleepwalked through the fall, refusing to either draw distinctions with Truman or a deeply unpopular Republican Congress. By the end, Truman’s famously negative appeal—the “give em hell” stump style that progressive populists relish to this day—works and at the tender age of 46, Dewey is reduced to the dust-bin of a three time loser whose career is memorable today only as a towering example of the fallibility of political polling.

Pietrusza also reminds us of several elements that are not generally remembered today, and that clarify our present circumstances. First, even with Dewey’s blunders, 1948 was, to quote Churchill on WWII, a “damned close run thing”. Had 29,000 votes in California, Illinois, and Ohio been reversed—the size of a city council turnout in a mid-sized city—Truman would not have won the electoral college and Strom Thurmond would have had his leverage. For all of the historical credit attached to the muscle unions provided Truman’s reelection, Dewey flipped six eastern, union-dominated states from Democratic four years earlier to the Dewey column. It was the Midwest farm belt, and its more conservative leaning voters, who went in the opposite direction, from GOP to Truman. In other words, the base vote mobilization strategy that is so associated with Truman’s success in 1948 was demonstrably less decisive than Truman’s ability to win back the moderates and independents of his era. (Indeed, California, the ultimate swing state that year, was far more agrarian and mid-western in its orientation than seems plausible now).

Pietrusza also reminds us of several elements that are not generally remembered today, and that clarify our present circumstances. First, even with Dewey’s blunders, 1948 was, to quote Churchill on WWII, a “damned close run thing”. Had 29,000 votes in California, Illinois, and Ohio been reversed—the size of a city council turnout in a mid-sized city—Truman would not have won the electoral college and Strom Thurmond would have had his leverage. For all of the historical credit attached to the muscle unions provided Truman’s reelection, Dewey flipped six eastern, union-dominated states from Democratic four years earlier to the Dewey column. It was the Midwest farm belt, and its more conservative leaning voters, who went in the opposite direction, from GOP to Truman. In other words, the base vote mobilization strategy that is so associated with Truman’s success in 1948 was demonstrably less decisive than Truman’s ability to win back the moderates and independents of his era. (Indeed, California, the ultimate swing state that year, was far more agrarian and mid-western in its orientation than seems plausible now).

Then there is the fact that Dewey’s Republican Party bears only a faint resemblance to the one today. It had its conservative flank, make no mistake, and Truman pilloried them for it, but the GOP was authentically progressive on civil rights. The Republican platform that year was explicit and visionary on the hot-buttons of the time—poll taxes, federal anti-lynching legislation—and Dewey’s own gubernatorial record had produced one of the toughest anti-discrimination laws in the country in New York. Dewey posed no challenge to the then relatively fledgling social security entitlement, and it is likely that he would have governed identically to his successor as Republican leader, Dwight Eisenhower, who left the New Deal untouched.

Pietrusza does not lean forward in this book, except in limited asides, to tell us how the story unfolded over the subsequent decades. The historical record is that Truman’s tactically ingenious victory was all but undone by war and red-baiting, and that civil rights and Medicare had to wait two decades for the evolution of a conservative Texas politico who makes a cameo appearance in “1948”, named Lyndon Johnson (he won a disputed 87 vote victory in a Senate primary after a campaign of bashing communists and denouncing federal civil rights laws). Moreover, the Republican Party turned hard right, and set itself on the anti-government path that characterizes it today. It is arguable that the bare-knuckle survival campaign of 1948 contributed to the polarization, and therefore undercut its own success.

I am told that Pietrusza’s book is already a favorite of certain Obama strategists. They shouldn’t miss the under-card to the great comeback story: the reality that winning ugly did not break the center-right nature of the country’s politics, that if anything it may have hardened the division, and that Truman’s second term was, for him, miserable. There are wins that come to look like losing.

Leave a Reply