The political cliché of the moment is “authenticity”, which its most avid users describe as a consistency of stated political beliefs; it is regarded as the moral opposite of “flip-flopping” or “pandering”. By the standards of the “authenticity” test, Mitt Romney is deeply flawed, having shifted views on the usefulness of healthcare reform, the legality of abortion, the literalness of the Second Amendment, and having discovered new reservations around the rights of gays and the claims of illegal immigrants.

The political cliché of the moment is “authenticity”, which its most avid users describe as a consistency of stated political beliefs; it is regarded as the moral opposite of “flip-flopping” or “pandering”. By the standards of the “authenticity” test, Mitt Romney is deeply flawed, having shifted views on the usefulness of healthcare reform, the legality of abortion, the literalness of the Second Amendment, and having discovered new reservations around the rights of gays and the claims of illegal immigrants.

This is a fair enough description. Romney rose as a Republican fending for votes in the most liberal state, Massachusetts, and neither his run against Ted Kennedy nor his governorship sounded very much like the standard form conservative trolling for early state Republicans today.

But the “authenticity” test finds fault in unexpected places. Barack Obama gets mixed grades at best. In the span from 2003 to 2008, his criticisms of the death penalty gave way to support for extending it to non death offenses like sexual abuse of minors; his support for stiffer gun laws turned into an endorsement of the Supreme Court’s rejection of tough local gun restrictions. The Patriot Act he assailed during the Senate campaign was a thing he voted to renew as a senator. As president, the forthright critic of non-judicial detention of suspected foreign terrorists has more or less copied the last administration’s playbook on the same subject. The candidate who jabbed his principal Democratic opponent for wanting to require that individuals purchase health insurance is now a president who has converted to the “mandates” cause.

But the “authenticity” test finds fault in unexpected places. Barack Obama gets mixed grades at best. In the span from 2003 to 2008, his criticisms of the death penalty gave way to support for extending it to non death offenses like sexual abuse of minors; his support for stiffer gun laws turned into an endorsement of the Supreme Court’s rejection of tough local gun restrictions. The Patriot Act he assailed during the Senate campaign was a thing he voted to renew as a senator. As president, the forthright critic of non-judicial detention of suspected foreign terrorists has more or less copied the last administration’s playbook on the same subject. The candidate who jabbed his principal Democratic opponent for wanting to require that individuals purchase health insurance is now a president who has converted to the “mandates” cause.

Obama has gotten no real grief for directions in the past several years that don’t match the things he said in the heat of campaigns to win liberal hearts in Illinois, and then the country. In contrast, it is George Bush who draws considerable ire for staying fixed in stone on Iraq, even when the results were a quagmire that nearly undermined the success of dethroning Saddam. If memory serves, Bush also won not much praise for sticking to his moderate stances on immigration: the Texas governor who aggressively courted Latinos was the same president who infuriated his base for favoring a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants.

It’s tempting, then, to say that the “authenticity” test is nothing but a test of our own politics: a politician who leaves the ideological place we want him to be, we view as a shape-shifter who is dishonest. We will cut an exception for the change artist who is still one of our guys, and we will give no credit for consistency when it isn’t one of our guys. We will be relentless in calling out the one we never liked, or the one who goes a change too far. It’s a convenient club, this “authenticity” thing, to be picked up when it serves other purposes.

But before going that far, a couple of modest caveats are in order. First, there is such a thing as growth in politics, as campaigning moves into governing. I disagree with Obama on insurance mandates for consumers and for that matter, businesses, but I grant him the credit of changing his views based on the hard, linear realities of constructing a healthcare regime that must simultaneously be accessible and affordable. I would not have ended up where he did, but his relative sincerity is not the defect I would cite. Similarly, any candidate who pleads a conversion based on discoveries about facts ought to be cut some slack in a political environment where facts are usually a minor condition of argument.

Second, in a profession where persuasion is the one necessary element of success, let’s spare ourselves exaggerated grief over candidates who say something at one rung on the political ladder and something different at another. It won’t, in fact, always be excusable, but it is in the DNA of a country whose sensibilities shift from one zip code to another. The politics of a state senator from Chicago’s brew of inner city and gentrified downtown simply would not have traveled well to Virginia or North Carolina. To be sure, a Republican governor who could function in a famously Democratic state made alliances, and concessions, that would be untenable in the base of a party that now leans hard right, if the prior record were the only evidence he could put on the table.

Is it plausible that a presidential candidate with as liberal a record as Obama circa 2000 could have shattered the racial glass ceiling in 2008? If you think not, but admire the shattering of the glass, you have just conceded the value of politicians moving as their constituencies evolve. If you believe it’s a good thing that the Republican field includes someone who governed a diverse state without tantrums or shut-downs, and would take that path over a party with an exclusively incendiary view of compromise, you are a Romney sympathizer whether or not you know it.

Third, if all “authenticity” means is a one note approach to complexity, none of us really want it. After all, it is Ron Paul who offers the most reliably consistent solutions over the course of his career, but a country stripped of its allies, its safety net, and its regulatory guard-rails seems not the answer.

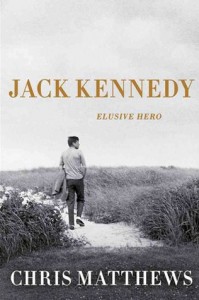

Then there’s the history you will find if Chris Matthews’s new bestseller is in your Christmas stocking. It’s about a nakedly ambitious young senator who was reticent, to put it mildly, about civil rights laws and the legal condition of blacks. When pressed, he’d lose all of his articulateness and mumble something about respecting the states’ prerogatives. In higher office, he “flip-flopped” and spent the last five months of his life, and his presidency, putting his prestige behind a law that broke segregation forever.

One of John Kennedy’s other biographers, William Manchester, observed that Kennedy was so enigmatic that you never knew what he bled or cried over, but that it didn’t matter because given power he acted. It’s a point, and it’s a powerful strike against confusing character and “authenticity”.

Leave a Reply