I don’t remember the phone call that changed my life as much as I remember later that night watching my father staring into his coffee cup four months after the funeral, watching my sister watch me, and thinking how soupbeans and apple preserves and cornbread for dinner reminded me of my mother.

Two

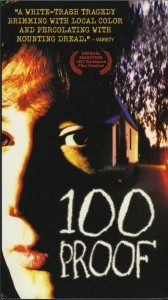

The prop car was already on fire by the time I overheard the two redneck brothers we hired as “pyro technicians” arguing about whose job it was to remove the gas tank. From 100 feet, I could smell melting vinyl and kerosene, and I wondered if Harold, our cinematographer circling above in a rickety prop plane, would continue to film after we had all blown up. I hoped he would. It was the last shot of the movie, and we could only afford one shitty 1982 Chevy Monte Carlo to set on fire, so it was now or never. The morning sky was slate and purple, and I thought about running, really, but I was too tired.

Three

-I’m sorry. Cooper who?

-John Cooper, from the Sundance Film Festival. People call me Cooper.

-Oh. Okay. Right. Yeah.

– I wanted to call and tell you that we loved 100 Proof. Thanks for sending the film to us. We’d like to have it in the Festival this year.

– Wait. Who is…? I’m sorry. Do what?

-We would like to have 100 Proof play at the Sundance Film Festival. It’s in January. Think you can make it…?

Four

You try to order French fries every hour or so, drink fountain RC and pay for the refills. Play the jukebox. When you write in restaurants, you learn ways to pay your freight. Eventually, people forget you are there. At the Dairy Bar across the river in Beattyville, KY, they know you as “Donnie and Mayme’s boy from Lexington–down here writing something.” You sit at the booth, put your watch in your pocket. Wait for the little bird to come sit on your shoulder. At night, you drive the Booneville road, eat a sandwich, turn into the county roads. Listen to Keith Whitley, maybe Elvis Costello. You’ve never written a movie; but know the first scene, and the last. Forget the middle tonight. It’ll be waiting for you tomorrow.

Five

New York City. Edie Falco rollerblades into the greek coffeeshop on 6th Avenue. She wants to talk about playing the lead. The Sopranos were still a few years away, and her agent didn’t want her to come, didn’t want her going to Kentucky for three months (why would you want to go to Kentucky…!?), didn’t want her playing a criminal, or taking a risk with a first-time filmmaker at this point in her career. So, before she even sits down:

New York City. Edie Falco rollerblades into the greek coffeeshop on 6th Avenue. She wants to talk about playing the lead. The Sopranos were still a few years away, and her agent didn’t want her to come, didn’t want her going to Kentucky for three months (why would you want to go to Kentucky…!?), didn’t want her playing a criminal, or taking a risk with a first-time filmmaker at this point in her career. So, before she even sits down:

– Why would I want to play this woman with no redemption, so little forgiveness.

– I don’t know. Because you can give her some?

– But how far can we take that before people run out of the theater?

We. It was the word “we” that I thought about later. What date would the Welles/Hayworth, Cassavetes/Rowlands relationship start? Me, the troubled director–she, the brilliant actress. What would our next film be? Three weeks later, after her agent won out, Edie regretfully said no, but recommended a friend she called the “best smart actress in New York” (Pamela Stewart, and she was so very right). Edie and I traded letters for a while longer. She always made it a point to mention redemption. She said I should look harder for it, in everything. I have those letters somewhere.

Six

You don’t think about end credits. I mean, you really don’t think about end credits until you’re sitting with your producer and going back through every moment of the last two years, trying to remember the Key Grip, or name of the guy you called at 5:30pm on that Tuesday when you needed a dog who could bark on cue. Extras and bit parts, the caterer who cut you a deal, the Gaffer and the Best Boy, the two redneck pyro guys. “Special Thanks” to include all the people who put up with your bullshit for the last three years. There’s a deadline, so you walk to the fax machine with the sheets, and you stare at the empty line you left on the bottom of the page. You take a pencil and scribble in the last credit: “For my mother, with so much love.”

You don’t think about end credits. I mean, you really don’t think about end credits until you’re sitting with your producer and going back through every moment of the last two years, trying to remember the Key Grip, or name of the guy you called at 5:30pm on that Tuesday when you needed a dog who could bark on cue. Extras and bit parts, the caterer who cut you a deal, the Gaffer and the Best Boy, the two redneck pyro guys. “Special Thanks” to include all the people who put up with your bullshit for the last three years. There’s a deadline, so you walk to the fax machine with the sheets, and you stare at the empty line you left on the bottom of the page. You take a pencil and scribble in the last credit: “For my mother, with so much love.”

Seven

Thirty minutes into our premiere, after I’d gone through my checklist of passive aggressive perfectionist asshole questions (Is the sound loud enough? Can you check the focus again? Is the projector bulb new?), Fred Mills, the gentleman manager of the Kentucky Theater, allows me sneak up to the old closed balcony and watch the movie from there. I stood overhead in the half-dark, studying the sides of faces, waiting to hear that little suck-in of breath when I knew the movie had them; when everyone was invisibly stuck together, taking a ride they weren’t expecting, not thinking about going to the bathroom, or fixing the rain gutters, or the fight they had on the way to the theater. Six years of my life for those 10 seconds? You betcha.*

* A month later, Fred tells me that the opening night crowd was total capacity–the first since the theater re-opened after the fire in 1987. The Kentucky sold more beer that week than ever before, and my friend David from high school fought a guy on Water Street who kept telling his buddies the movie sucked.

Eight

| The Final Tally | ||

| Budget | $220,000 | |

| On My Credit Cards | $32,000 | * |

| Girlfriends | 2 | |

| Apartments | 3 | |

| Friends Lost | 1 | ** |

| Cars (personal) | 2 | |

| Cars (burned up) | 1 | |

| Screenings (US) | 500+ | *** |

| Reviews (major papers) | 12 | |

| Reviews you claim to have not read, but of course you did | 12 | |

| Times you walked into the Blockbuster on Euclid Ave. to see if your movie was rented | 0 | **** |

| Pounds Gained | 25 | |

| Filthy Oaths | 10,251 | ***** |

| Years | 6 | |

| Days | 2190 | |

| Days (Joy) | 2190 | |

| Days (Sadness) | 2190 | |

| Days (Regret) | 0 | |

| * Estimate–I stopped counting at a certain point | ||

| ** Más vale solo que mal acompañado | ||

| *** Estimate, minus weird travelling tour of Australian outback | ||

| **** Ha ha ha ha (right….) | ||

| ***** Exact number | ||

Nine

She used to come by herself to the theater at night and stand in the back and watch the plays you directed. She told you stories about your grandfather who painted murals for the WPA, and that he died at age 45 behind the smokehouse where he would sit and sketch crows and fences. She wanted you to be a lawyer, but when you graduated high school, she bought you a correctable typewriter. She said, “Do what you want”, and the inflection was softly on the word “you”. She had colored her hair the day she visited the set, and you told her how good it looked. Later, after she had gone back home, you realized that it was a wig; that she now had to wear a wig. Your problems meant nothing.

After all this had happened, one morning in her hospital bed she died while you held her hand. She never got to see your film in a theater. She never got to fly in an airplane.

Ten

It’s funny, but as I walked across the parking lot towards the Japanese steakhouse that March evening in 2003, I knew the ride was finally over; and I felt relieved and excited and only the tiniest bit sad.

A few weeks before, half-asleep/half-listening to some endless series of dull political speeches on C-SPAN, I had heard a low audience murmur grow sharply into an excited roar. I reached over and turned up the remote. On the television, people were cheering, and they weren’t stopping:

A few weeks before, half-asleep/half-listening to some endless series of dull political speeches on C-SPAN, I had heard a low audience murmur grow sharply into an excited roar. I reached over and turned up the remote. On the television, people were cheering, and they weren’t stopping:

“I’m Howard Dean, and I want my country back!”

Two weeks later, across that parking lot and into the Japanese steakhouse, I had organized the first Howard Dean “MeetUp” in Lexington. By the time Howard Dean screamed in Iowa, the Dean for America organization had grown into more than 2000 activists across Kentucky. Eventually, at the request of a certain blogger, I became the Executive Director of the Kentucky Democratic Party. Sitting in the dark in my office that first night, I thought back to that night in the Kentucky Theater, everyone invisibly stuck together, taking a ride they weren’t expecting.

Eleven

A couple of weeks ago, I was in Beattyville.

Leave a Reply