NATO’s operations in Libya have created a very odd moment in international affairs. The decision to commit US and NATO forces to help the embattled rebels by imposing a no fly zone happened so fast there was barely any time for an actual debate. The momentum for swift action, however, has dissipated now that the decision has been made, leaving us with a stalemate on the ground and with lingering concerns that, almost in a fit of insensibility, the US and its allies have begun an adventure without any clear idea of how or when it will end.

The political contortions surrounding the decision to act will keep historians and political scientists busy for years. It offered, for example, the confusing spectacle of the Secretary of Defense going into detail about what a bad idea a no fly zone was only a few days before the decision to go ahead. The President made the decision while traveling in Latin America, and only spoke to the American people in detail several days after the air war began. The political class was similarly confused.

Only relatively marginalized groups on Right and Left offered clear objections—Glenn Beck seeing in the Arab Spring a global conspiracy of liberals and Islamists to establish a Caliphate; Dennis Kucinich wanting to impeach the President for going to war—but the political establishment acquiesced quickly to the arguments for action. Congressional Democrats, many of whom had been vocal critics of military actions elsewhere, closed ranks around the President. Congressional Republicans were caught flat-footed, and after a period of confusion settled on a strategy of criticizing the manner in which the decision was made rather than the decision itself.

The international reactions have been no less confused. Europeans, concerned about the unrest in a country so close to their shores and which provided so much of Europe’s oil, were among the first calling for action, seconded (incongruously enough) by the Arab League. Calls for a no fly zone grew as it appeared that TheBrotherLeaderWhoseNameWesternMedia-HasNotBeenAbleToTransliterateEffectivelySince1969 was preparing to massacre the rebels in the besieged towns and cities of Eastern Libya. With President Obama arguing that the US could not go it alone, and our most important European allies expressing a willingness to shoulder a large share of the burden, the UN Security Council supported the idea, and voila! A triumph of multilateralism.

Except…

Yes, the Security Council managed to avoid a Russian or Chinese veto, but the best those two international free riders could offer was to abstain. Neither China nor Russia has made any constructive contribution to settling the problems, and no one expects them to either, which is incongruous but habitual for two states who enjoy complaining about American unilateralism. To make matters worse, the Germans, in the person of Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle, who had spoken so loudly in the run-up to the vote about the need to avoid a humanitarian catastrophe, joined China and Russia in the abstention. Westerwelle and his boss, Chancellor Angel Merkel, had their eyes on upcoming state elections and decided not to rile the German public by committing the Germans to military action—thus choosing to be preemptively irresponsible rather than provide ammunition for their even more internationally irresponsible domestic rivals. Westerwelle then doubled down on the pusillanimity by announcing that the German abstention did not mean the Germans would not support allied actions in general, as if fecklessness and opportunism are somehow more appealing when one makes no effort to hide them. In the end, the German government was rightfully pummeled from all sides, continues to earn the scorn of media critics (such as Roger Cohen in the NY Times), has alienated its allies, and lost the big state election in Baden-Württemberg anyway.

Meanwhile, France, with Britain close behind, has taken a leading role in the Libya action (and, partially in response to critics who said the West did not care about non-oil-producing lands, Ivory Coast as well). Recent French actions would overturn all the American canards about French weakness and cowardice so popular in the debate over Iraq, if the people who traffic in such canards actually allowed themselves to be swayed by actual facts. One should of course not over-praise French willingness to act, since it reflects domestic politics as much as the German decision. President Nicolas Sarkozy has calculated that these actions will help burnish his image as a leader as he attempts to rev up his re-election campaign. Whether it will do that remains to be seen. In this case, however, the French government has both made a clear decision and has backed it up with actions.

Now we have an open-ended commitment to police the skies over Libya being run by NATO, which provides a nice multilateral façade for the action. Underneath, things are not so harmonious, which anyone who knows anything about NATO could have predicted. For one, the alliance has always relied heavily on American hardware, leadership, and troops, making President Obama’s claims that the US is somehow not strongly involved rather disingenuous. Also, the European members of the alliance, with their wide range of capabilities, interests, and preferences, are far from united, which does not bode well for long-term decision-making. The Germans are merely the most embarrassing example of a wider problem. Some politicians and analysts (including this author) have dreamed of the day when the Europe would have a credible joint security policy that would allow Europeans to take action without depending on American power. Alas, that day is as far off now as it was back in 1992, when the Europeans claimed they could handle the breakup of Yugoslavia without American assistance. Thus we have France and Britain doing the heavy lifting, with other NATO members, such as Norway, offering what small resources they have available. Furthermore, the shaky consensus in favor of policing the skies over Libya threatens to fall apart whenever alliance members discuss the possibility that supporting the rebels will require at the very least arming and training them, and at the most an actual ground intervention.

So, despite the earnest efforts of Presidents Obama and Sarkozy, British Prime Minister David Cameron and NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen to provide an image of alliance unity and resolve, one cannot shake the uncomfortable feeling that the US and its allies have only the vaguest sense of what they hope to accomplish in Libya, and no clear idea of what they should do next to accomplish it.

Where does all this leave us? As a spur to further discussion, I would like to conclude with three interlocked observations inspired by the Libya situation, and look forward to hearing your responses.

- Process Is Nice, But It Is Not Policy

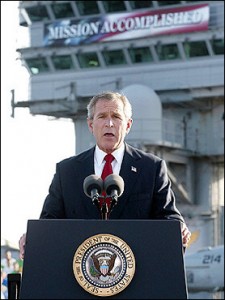

One of the most common criticisms of George W. Bush’s foreign policy was that the United States preferred unilateral to multilateral action, ad hoc coalitions of the willing to existing alliance structures. That was certainly true, and worth criticizing, but focusing on the form of US policy begged two larger questions: whether the actual policy was acceptable, and whether the imagined allies were actually available. If one approved of the decision to attack Iraq, for example, and if the available organizations were (for whatever reasons) unable or unwilling to join in, then the complaints about American unilateralism are nothing more than side issues. If one opposed the war in Iraq, on the other hand, does it really matter whether the US acted alone or with allies? The wrong lies in the function (that is, the policy), not the form. Criticism should focus on the war being wrong, rather than scoring points with a carping about the coalition, or the manner in which the decision was reached. The obverse is also true: the Obama administration did all the right multilateral things in reaching the decision to act in Libya, but getting the process right does not automatically redeem hasty or poorly thought-through policy. Multilateral quagmires are as sticky as unilateral ones, even if one can be comforted by the presence of good friends in the muck.

One of the most common criticisms of George W. Bush’s foreign policy was that the United States preferred unilateral to multilateral action, ad hoc coalitions of the willing to existing alliance structures. That was certainly true, and worth criticizing, but focusing on the form of US policy begged two larger questions: whether the actual policy was acceptable, and whether the imagined allies were actually available. If one approved of the decision to attack Iraq, for example, and if the available organizations were (for whatever reasons) unable or unwilling to join in, then the complaints about American unilateralism are nothing more than side issues. If one opposed the war in Iraq, on the other hand, does it really matter whether the US acted alone or with allies? The wrong lies in the function (that is, the policy), not the form. Criticism should focus on the war being wrong, rather than scoring points with a carping about the coalition, or the manner in which the decision was reached. The obverse is also true: the Obama administration did all the right multilateral things in reaching the decision to act in Libya, but getting the process right does not automatically redeem hasty or poorly thought-through policy. Multilateral quagmires are as sticky as unilateral ones, even if one can be comforted by the presence of good friends in the muck.

2. Military Action Means Military Action

As much as Defense Secretary Gates may now find his public statements against no fly zones politically embarrassing, he deserves credit for actually telling the truth. One cannot simply declare a no fly zone. Establishing one requires bombing radar installations and air bases, and regular vigilance. Furthermore, if the purpose of air superiority is to inhibit the movement of military forces, it requires attacking forces on the ground as well. That means people will get hurt, and not just “bad guys.” The back and forth reaction of the Arab League to the NATO action—first demanding it, then denouncing it when bombs began to fall—is but the most glaring example of how poorly even supporters of the Libya mission considered this basic reality. Moreover, all air power will do is stabilize a situation. If the goal is rolling back the Libyan government forces, that will require much more direct intervention, not bombing from thousands (or even hundreds) of feet up. To pretend otherwise is to substitute wishing for policy. Air power has fascinated theorists for a century, and has encouraged such wishful thinking, especially in states that want to risk the lives of as few of their own voters as possible. That kind of irresponsibility is what leads people to believe that “shock and awe” will solve all problems. It is maddening to see the same wishful thinking applied yet again. We need to think this through: If saving Libya’s revolution is important enough to bomb Libya, it is important enough to intervene on the side of the rebels. If it is not important enough to justify an intervention on the side of the rebels, it is not important enough to bomb Libya. Or, to put it more bluntly: If you do not want to shoot anybody, stay out of the war. But don’t get involved in a war and pretend you can achieve your goals without shooting anybody. This is neither an argument for militarism or for pacifism. It is an argument for honesty with oneself, one’s allies, and even one’s enemies.

3. Europe is Failing Its Latest Global Test

The Libya crisis provided an excellent moment for Europeans to have an honest discussion of their vision for Europe’s international role, especially at a moment when the political and economic pillars of European integration are in the midst of a serious crisis thanks to the problems of sovereign debt and the Euro. So far, the Europeans have failed to live up to this moment. The actions of France and Britain and a few other NATO members cannot hide the failure of the EU (which is supposed to be the embodiment of Europe as a whole) to offer clear political guidance and unfiled leadership. Don’t get me wrong. I am not some neocon who enjoys mocking “Old Europe” and its postmodern fantasies of soft power. As a historian and analyst of European integration, I think that a strong Europe able to act independently in all aspects of international affairs would be an unalloyed positive for the international community. But Europe has so far failed to construct the organizations necessary to do this. They failed to do it during the Cold War; they have failed to do it since the end of the Cold War. (The details there are probably better saved for a future post.) The villain here is not George Bush. Europeans have done this to themselves by dodging the issue, and hiding behind criticisms of the naughty Americans to obscure their own failures. There is still time for Europeans to develop such institutions, but that will require political courage, both on the part of strong states like Britain and France, who will need to integrate their forces into a larger European structure, and to the smaller states, who will need to make a constructive contribution to the general cause. It will especially require political courage from the Germans, who need to see that it is not enough to talk of solving the world’s problems. No one should believe that every problem has a military solution. But some do, and responsible international actors should be prepared to respond constructively to them, not to simply stand back and let someone else do it.

The Libya crisis provided an excellent moment for Europeans to have an honest discussion of their vision for Europe’s international role, especially at a moment when the political and economic pillars of European integration are in the midst of a serious crisis thanks to the problems of sovereign debt and the Euro. So far, the Europeans have failed to live up to this moment. The actions of France and Britain and a few other NATO members cannot hide the failure of the EU (which is supposed to be the embodiment of Europe as a whole) to offer clear political guidance and unfiled leadership. Don’t get me wrong. I am not some neocon who enjoys mocking “Old Europe” and its postmodern fantasies of soft power. As a historian and analyst of European integration, I think that a strong Europe able to act independently in all aspects of international affairs would be an unalloyed positive for the international community. But Europe has so far failed to construct the organizations necessary to do this. They failed to do it during the Cold War; they have failed to do it since the end of the Cold War. (The details there are probably better saved for a future post.) The villain here is not George Bush. Europeans have done this to themselves by dodging the issue, and hiding behind criticisms of the naughty Americans to obscure their own failures. There is still time for Europeans to develop such institutions, but that will require political courage, both on the part of strong states like Britain and France, who will need to integrate their forces into a larger European structure, and to the smaller states, who will need to make a constructive contribution to the general cause. It will especially require political courage from the Germans, who need to see that it is not enough to talk of solving the world’s problems. No one should believe that every problem has a military solution. But some do, and responsible international actors should be prepared to respond constructively to them, not to simply stand back and let someone else do it.

No one can say how the Libyan situation will turn out. But it offers an excellent opportunity for both supporters and critics of the policy to think honestly about how we got where we are, and where we want to go. Let the conversation begin.

Leave a Reply