Last week, I wrote about my father, Robert Kennedy, and his critique of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as the measure of national well-being. He said, “It measures everything except that which makes life worthwhile. And it can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.”

Had my father lived, we might have started work a lot sooner on truer ways to measure the state of the nation. Sadly, that did not happen. His critique of the GDP was forgotten. Instead, other values came to govern American life.

In 1968, David Frost asked both Ronald Reagan and my father to speak on the purpose of life. Ronald Reagan answered:

Well, of course, the biologist I suppose would say that like all breeds of animals, the basic instinct is to reproduce our kind, but I believe it’s inherent in the concept that created our country–and in the Judeo-Christian religion–that man is for individual fulfillment; for our religion is based on the idea not of any mass movement but of individual salvation. Each man must find his own salvation; I would think that our national purpose in this country–and we have lost sight of it too much in the last three decades–is to be free–to the limit possible with law and order, every man to be what God intended him to be.

My father said:

I think you have to break it down to people who have some advantages, and those who are just trying to survive and have their family survive. If you have enough to eat, for instance, I think basically it’s to make a contribution to those who are less well off. ‘I complained because I had no shoes until I met a man who had no feet.’ You can always find someone that has a more difficult time than you do, has suffered more, and has faced some more difficult time one way or the other. If you’ve made some contribution to someone else, to improve their life, and make their life a bit more livable, a little bit more happy, I think that’s what you should be doing.

Ronald Reagan’s views came to dominate the political landscape. Later, when he was asked what he meant by freedom, he described driving up the Pacific Coast Highway in a convertible with the wind blowing through his hair. Here was a man truly doing his own thing, alone.

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson had nice houses. They could have enjoyed contented private lives. But it was not just about their property.

What Ronald Reagan is remembered for does not reflect what he actually did. Of course, he believed in public engagement. He was a six-term president of the Screen Actors guild, calling union membership a “fundamental human right.” He was governor of California and president of the United States. He spoke eloquently about America as a “shining city on a hill.”

Reagan is remembered, however, not for any detailed description of how to actually build that city, but for his anti-government rhetoric. He conflated freedom with unfettered markets, and his legacy was a glorification of private wealth over the public good.

Today, economics, with its misapprehension that human beings are cost/benefit calculating machines, has come to dominate our politics and our lives. We’re left with an unnatural obsession with individualism, a single-minded focus on wealth over work, and an anti-government animus. We’re obsessed by supply and demand, driven by marketing and advertising to buck up and demand more to meet the burgeoning supply. The result has been devastating. Millions have been harmed.

As I wrote last week, economists and leaders have begun to search for alternative ways to value the lives of individuals and evaluate the success of nations. Since many of the questions they’re raising are philosophical, voices from the past may be helpful.

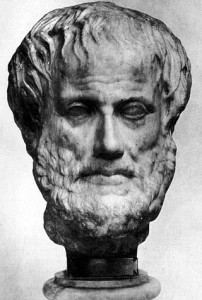

The Greeks, for instance, were very interested in well being. Aristotle thought happiness was the goal of human activity. For him, true happiness was something more than simply “Eat, drink, and be merry,” or even the honor of high position. Real satisfaction didn’t depend on the pleasures of the senses or what others thought of you. You could find genuine happiness only in a life of virtue and just actions. President Kennedy alluded to Aristotle when he defined happiness as “the full use of one’s talents along the lines of excellence.”

The Greeks, for instance, were very interested in well being. Aristotle thought happiness was the goal of human activity. For him, true happiness was something more than simply “Eat, drink, and be merry,” or even the honor of high position. Real satisfaction didn’t depend on the pleasures of the senses or what others thought of you. You could find genuine happiness only in a life of virtue and just actions. President Kennedy alluded to Aristotle when he defined happiness as “the full use of one’s talents along the lines of excellence.”

For the Greeks, excellence could be manifest only in a city or a community. Since human beings were political animals, the best way to exercise virtue and justice was within the institutions of a great city (the polis). Only beasts and gods could live alone. A solitary person was not fully human. In fact, the Greek word “idiot” means a private person, someone who is not engaged in public life. It was only in a fair and just society that can men and women could be fully human–and happy.

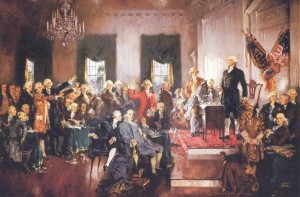

This is what the American Revolution was all about. Jefferson declared that the pursuit of happiness was an inalienable right, along with life and liberty. The story goes that Jefferson, on the advice of Benjamin Franklin, substituted the phrase “pursuit of happiness” for the word “property,” which was favored by George Mason. Franklin thought that “property” was too narrow a notion.

But what exactly did “happiness” mean to the colonists? It was a topic of lively discussion in pubs, public squares, broadsheets, and books. Was happiness individual prosperity, or something else?

Conservatives argue that the American Revolution exalted the individual. Certainly, the colonists didn’t want the British Crown telling them what to do. But the Revolution wasn’t just about getting the government out of people’s lives so the Founders could pursue their private desires.

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson had nice houses. They could have enjoyed contented private lives. But it was not just about their property. They believed that you attained happiness, not merely through the goods you accumulated, or in your private life, but through the good that you did in public. People were happy when they controlled their destiny, when their voice was heard, when they participated in public events, when the government did not do things to them, or even for them, but with them.

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson had nice houses. They could have enjoyed contented private lives. But it was not just about their property. They believed that you attained happiness, not merely through the goods you accumulated, or in your private life, but through the good that you did in public. People were happy when they controlled their destiny, when their voice was heard, when they participated in public events, when the government did not do things to them, or even for them, but with them.

The American revolutionaries wanted to have their voice heard and to participate in government. After all, their slogan was not “No taxation”–which is such a popular rallying cry today–but “No taxation without representation.” Representation was critical to happiness. The Founders’ long recitation of grievances set out the numerous ways in which they couldn’t control their destiny. They were subject to England, while they wished to be citizens of America. As citizens, they were able to take control of their government and create a just state where the rule of law was respected, domestic tranquility assured, and defense maintained.

As political animals, human beings need a city, a nation, in which to flourish. People can develop their talents only in society. The good society nurtures many talents, and the political system makes that possible by what it rewards and encourages.

This brings me to jobs. After the crash of 2009, banks have been saved, corporations are prospering, and people are still unemployed. My father would have seen something wrong with this picture. He believed having a good job was the key to happiness. “The root problem,” he said, “is in the fact of dependency and uselessness itself. Unemployment means having nothing to do, which means nothing to do with the rest of us. To be without work, to be without use to one’s fellow citizens, is to be in truth the invisible man of whom Ralph Ellison wrote.”

In the face of our stubborn economic crisis over the past few years, our solutions would have been different if we had believed that jobs were our top priority. We could have put people to work rebuilding our roads, railroads, bridges, sewage and public water systems, transmission lines for wind and solar energy. There was much to be done if we had been able to see it.

There is still much to be done. We need to create and sustain jobs that let men and women say to their community, to their family, to their country, and most important, to themselves, “I helped to build this city. I am a participant in its great public ventures. I count.”

It’s not only through our jobs but through participating in public life that we help build the city. In fact, research shows that people who take part in political activities such as voting, advocating for laws, and helping to make government work for themselves and their community are happier than those who don’t.

At the moment, unfortunately, few people would regard building the city as a source of happiness, even when they’re doing it. A few weeks ago, I was at a political event in Washington. Over 12,000 people from all over the country had come to participate. When I asked the woman who was standing next to me what made her happy, she described the purchase of a lovely piece of pottery. She never thought of saying, “Standing here, working for my country, making my mark on American policy.” Yet she had devoted hundreds of hours to doing just that. She simply did not see what she was doing. She didn’t have a name for it.

Surveys won’t give her the answer. Only thoughtful discussions of the true meaning of happiness and prosperity will awaken people to what it is that really fulfills them and will give them the words to describe it.

(Cross-posted, with permission of the author, from Atlantic.com)

Leave a Reply