By 2060, the Americas are projected to have a larger population than China, so shouldn’t we direct more attention to our southern neighbors?

By 2060, the Americas are projected to have a larger population than China, so shouldn’t we direct more attention to our southern neighbors?

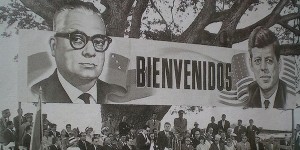

A great nation defines itself not by what it fears and opposes but by what it believes in and champions. This year is the 50th anniversary of the Alliance for Progress, President Kennedy’s visionary effort to promote social justice and economic development in Latin America. The Alliance had a short ten-year life, but its influence was real, and its vision of the Americas is still relevant today.

The Alliance was a wager on the capacity of progressive democratic governments to carry out a peaceful revolution with the help of political support and carefully designed economic assistance.

The idea for the Alliance grew from my uncle’s capacity to listen to the leaders of Latin America, and from his openness to what he heard. The leaders said, “The United States in all its power and wealth and influence should be our partner as we build a more just society for all our citizens.” They added, “This partnership must be built on respect for the values and vision of the southern hemisphere.” John Kennedy took their arguments seriously.

In launching the Alliance, he built on the work of Douglas Dillon, who in 1958 had attended a three-week meeting in Brazil as a State Department employee. Dillon was impressed by Latin America leaders, particularly those from Brazil and Mexico, who were urging a new coffee agreement and a new development bank for the Americas. He eventually prevailed on President Eisenhower to take up the cause and to create the Inter-American Development Bank. He also piqued the interest of the Democratic presidential candidate from Massachusetts.

State Department employee. Dillon was impressed by Latin America leaders, particularly those from Brazil and Mexico, who were urging a new coffee agreement and a new development bank for the Americas. He eventually prevailed on President Eisenhower to take up the cause and to create the Inter-American Development Bank. He also piqued the interest of the Democratic presidential candidate from Massachusetts.

As Arthur Schlesinger recounts it, Senator Kennedy read a memorandum from ten leading Latin American economists, and, impressed with the urgency and energy of their ideas, conceived of a new approach to inter-American development.

He had an idea but no name.

Sitting in the campaign bus as it rolled across Texas, Dick Goodwin, his speechwriter, groped for a phrase that would express what the “Good Neighbor Policy” did for Franklin Roosevelt. As he pondered, his eye caught the title of a Spanish language magazine, Alianza. He liked that, but then the question was, Alliance for what? A call was placed to Ernesto Betancourt, then at the Pan American Union, who had two suggestions: Alianza para el Desarollo (development) and Alianza para el Progresso. That’s how the Alliance was christened.

Once he was elected, my uncle asked Douglas Dillon, a Republican, to serve as treasury secretary. (My brother Douglas was named for him.) It’s worth noting that at its beginning, the Alliance for Progress had strong bipartisan support.

In his inaugural address, the new president proclaimed his vision for the Americas: “To our sister republics south of our border, we offer a special pledge: to convert our good words into good deeds in a new alliance for progress, to assist free men and free governments in casting off the chains of poverty.”

Later, in a talk with the Latin American diplomatic corps in the East Room of the White House, President Kennedy signaled that the Alliance was no mere window dressing.

At the heart of the Alliance was a call for fundamental openings in the economic and political systems of the Americas that would let the dispossessed claim their place in the sun. The status quo was unacceptable. My uncle said, “Those who make peaceful revolution impossible make violent revolution inevitable.” He called for democracy, a new respect for human rights, long-term economic development, fair distribution of the fruits of growth to campesinos and workers, and land, tax, and education reform.

The president spoke about the Americas with passion and energy. He knew that without lofty goals, the Alliance couldn’t inspire people’s imagination and their determination to root out hundreds of years of entrenched political and economic power.

Latin American oligarchs felt threatened, as did their allies at State, the Pentagon, Treasury, and the CIA. Some feared armed rebellion, others communism, others a threat to American business interests.

Despite the challenges, the Alliance caused tangible change: schools, hospitals, low-cost housing, and roads were built, and irrigation and electric power systems improved. In its first six years, its partner countries exceeded the growth rate set out in the original charter agreement. Multilateral initiatives strengthened each country’s planning capacity and spread successful development practices across the region.

Sadly, after President Kennedy died and the Vietnam War escalated, the United States became distracted and the forces of reaction reasserted themselves. In 1965, my father–about to leave on a trip to Latin America–asked the assistant secretary for inter-American affairs why the U.S. was cutting off aid to a government in Lima dedicated to the goals of the Alliance and at the same time increasing aid to a new military dictatorship in Brazil.

After hearing that U.S. business interests were at stake, my father replied: “You are saying that what the Alliance for Progress has come down to is that if you have a military takeover, outlaw political parties, close down the Congress, put your political opponents in jail, and take away the basic freedom of the people, you can get all the American aid you want. But if you mess around with an American oil company, we’ll cut you off without a penny. Is that right? Is that what the Alliance for Progress comes down to?” The assistant secretary said, “That’s about the size of it.”

Happily, fifty years later, at least some of this cynicism has been replaced by renewed hope. National budgets and GDP growth in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Peru are in far better shape than our own. Some Central and South American governments have pioneered creative approaches to helping poor families while promoting school attendance and early childhood medical care.

Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Peru are in far better shape than our own. Some Central and South American governments have pioneered creative approaches to helping poor families while promoting school attendance and early childhood medical care.

Of course, we still have miles to go. The drug trade continues to wreak havoc in many nations of Central America, and deforestation is becoming an increasingly critical issue as climate change progresses.

The original vision of the Alliance for Progress points the way forward. President Kennedy understood that the greatest threats in the hemisphere were debt, poverty, and unemployment–not guerrillas or Soviet influence. He knew that the United States could be both an economic force and a force for social justice. And he saw that America’s natural allies in the region were democratic leaders who were humane, moderate, pragmatic reformers. These insights remain as true today as they were fifty years ago.

Fifty years from now, the Americas will have a greater population than China. We’re all in it together. We should recommit ourselves to building a new relationship in this hemisphere between the developed and developing worlds, one that that can serve as a model for countries everywhere.

What a great challenge to build an alliance among nations where the rights of all citizens are protected under law, the environment is preserved, co-operation and respect among countries are the norm, the fruits of rising prosperity and permanent peace are shared by all, and our children can pursue their dreams as far as their talent and passion will take them.

(Cross-posted, with permission of the author, from Atlantic.com)

Leave a Reply