Let’s begin with what “The Ides of March” won’t be: it will contend for no Oscars, it does not threaten the exclusive club status of “All the President’s Men” or “Primary Colors”, and it lacks the camp appeal of “W.” It is, however, the latest cinematic attempt to demonstrate that the past-time of people like us is actually kind of watchable, and interesting, and if we selfishly want to see more of our dreamworld being glamorized, our kind should care if this sort of thing still makes good movies.

Let’s begin with what “The Ides of March” won’t be: it will contend for no Oscars, it does not threaten the exclusive club status of “All the President’s Men” or “Primary Colors”, and it lacks the camp appeal of “W.” It is, however, the latest cinematic attempt to demonstrate that the past-time of people like us is actually kind of watchable, and interesting, and if we selfishly want to see more of our dreamworld being glamorized, our kind should care if this sort of thing still makes good movies.

Hollywood, by the way, senses that politics usually does not sell, and it makes its accommodations to this reality. This spring’s “Adjustment Bureau” shunned its political story-line in its own advertising, and another momentary flash in the pan, Bradley Copper’s “Limitless”, tacks on a political sub-plot only in the final ten minutes (it works as well as trying to work a fender bender in the studio parking lot into the action.) Even a film that is unambiguously about a political figure, the upcoming “J. Edgar”, exists more because of the tangled webs that apparently existed in Hoover’s private life, than because he blithely abused the prerogatives of federal law enforcement through the terms of eight presidents.

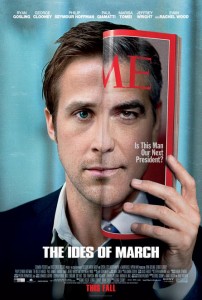

So, when the big screen goes there anyway, and tries to make cash out of politics, its strategy is to bet on the best and most charismatic talent it can get. “J. Edgar” has DiCaprio, and the “Ides” has George Clooney–this generation’s successor to Robert Redford as the man progressives wish were as politically ambitious as he is politically active. Clooney is excellent for the usual reasons–the effortlessness, the cool, the sense that being him is a pretty good, unfair for the rest-of us deal. Ryan Gosling, at this stage in his stardom, has a charisma rooted more in a look than a persona, and he is neither strikingly good nor appallingly bad here. Then there is the wickedly brilliant Phillip Seymour Hoffman, who is superb, and continues his gift for making warped personalities likable–no accident that he pulls off one of the movie’s few surprise turns, doing a slimy thing for the most high-minded of reasons, and making a pretty good speech about it!

So, when the big screen goes there anyway, and tries to make cash out of politics, its strategy is to bet on the best and most charismatic talent it can get. “J. Edgar” has DiCaprio, and the “Ides” has George Clooney–this generation’s successor to Robert Redford as the man progressives wish were as politically ambitious as he is politically active. Clooney is excellent for the usual reasons–the effortlessness, the cool, the sense that being him is a pretty good, unfair for the rest-of us deal. Ryan Gosling, at this stage in his stardom, has a charisma rooted more in a look than a persona, and he is neither strikingly good nor appallingly bad here. Then there is the wickedly brilliant Phillip Seymour Hoffman, who is superb, and continues his gift for making warped personalities likable–no accident that he pulls off one of the movie’s few surprise turns, doing a slimy thing for the most high-minded of reasons, and making a pretty good speech about it!

The script, based on a play by a former Howard Dean staffer, is not heavy creative lifting: idealistic, brilliant young campaign aide is convinced he has found the presidential candidate who will transform America, and shake politics out of its doldrums, but who requires the young aide to craft the lines that lift our souls–the kind of marriage regularly dreamed about at the nearest version of the Kennedy School near you. Said campaign aide, on the way to glory, is tempted by a rival who works his ego and a sexy, conveniently available junior staffer who has her own wiles, and (wouldn’t you know?) her own secrets. So far, so familiar. Then, as these things go, campaign aide stumbles onto explosive revelation that could change everything, and learns, of course, that his trust has been abused. There must be tragedy and one final sordid little deal before the credits.

As conventional as the plot is (You might not get Clooney, but you could write this), the movie does an altogether decent job of making the motions at least seem authentic. I’ve read that some Beltway types disagree, but I found it consistently realistic when it resorts to campaign minutiae: staffers of a certain age do affect the bravado “managing down”, the obsequiousness “managing up” that Gosling does well; in campaigns, as in this movie, there are rooms of dysfunctional people navigating crises that seem momentarily significant, while in the intervals in between, they maneuver to supplant or seduce other people in the room. There are operatives peddling half-truths, would-of-been contenders trying to cut deals–never seen that before. It doesn’t happen quite this way, but something quite like all of this does happen.

As conventional as the plot is (You might not get Clooney, but you could write this), the movie does an altogether decent job of making the motions at least seem authentic. I’ve read that some Beltway types disagree, but I found it consistently realistic when it resorts to campaign minutiae: staffers of a certain age do affect the bravado “managing down”, the obsequiousness “managing up” that Gosling does well; in campaigns, as in this movie, there are rooms of dysfunctional people navigating crises that seem momentarily significant, while in the intervals in between, they maneuver to supplant or seduce other people in the room. There are operatives peddling half-truths, would-of-been contenders trying to cut deals–never seen that before. It doesn’t happen quite this way, but something quite like all of this does happen.

The movie’s problem is the opposite of being unreal; to the contrary, its most conspicuous failing is the way it takes exactly the turns we expect, the way its blemishes are all the ones we imagine. Rather than strain credulity, the “Ides” gives us just what we think we know–a confirmation that the whole political game is riddled with the phoniness that most voters suspect, and perhaps a cautionary note, as if we needed it, against filtering our aspirations through the lens of hero worship. But the best political fiction in our time was “West Wing”, which was cynical, myth-shattering, yet never so scarred that it didn’t inspire: the show was exemplary because it made politics and leadership seem vital and dynamic, but only barely, and in spite of the mere mortals who wander in it. President Bartlett was a scheming, vain, stubborn man who intuitively felt how government should work–in other words, kind of life-like in his complexity, just a better president than most of the real ones.

The movie’s problem is the opposite of being unreal; to the contrary, its most conspicuous failing is the way it takes exactly the turns we expect, the way its blemishes are all the ones we imagine. Rather than strain credulity, the “Ides” gives us just what we think we know–a confirmation that the whole political game is riddled with the phoniness that most voters suspect, and perhaps a cautionary note, as if we needed it, against filtering our aspirations through the lens of hero worship. But the best political fiction in our time was “West Wing”, which was cynical, myth-shattering, yet never so scarred that it didn’t inspire: the show was exemplary because it made politics and leadership seem vital and dynamic, but only barely, and in spite of the mere mortals who wander in it. President Bartlett was a scheming, vain, stubborn man who intuitively felt how government should work–in other words, kind of life-like in his complexity, just a better president than most of the real ones.

“The Ides” would have worked better if its crafters had slipped it onto cable, perhaps as a Showtime project or HBO’s next gamble: spread over 8 to 10 episodes, it would have had the time to pump a little more nobility into the hero candidate before he gets unmasked, or better yet, create some genuine ambiguity around the motivations of the cast that rushes a little too briskly through this narrative.

“The Ides” labors with another burden, and it is one of the reasons politics is typically bad box office. The secrets just aren’t secret anymore. The public that idolized “All the President’s Men” thought it a revelation that the “smoke filled” rooms are filled not with smoke but deceptions and manipulation and sometimes criminal schemes. The “secret” at the heart of the “Ides of March” has happened all too recently (it’s a couple of scandals stitched together) and if something like it happened it again, there would be much sanctimony, much disgust, but no real shock. Like the underlying rhythm of the “Ides”– the manipulations of ego, the lack of fidelity to ethics, the idealist’s willingness to cut corners–it is all rooted in what we expect of politics, and a movie that dwells on it gives neither an escape nor a life lesson.

Lastly, a few have complained that a picture with no real chance of a sequel ends too unresolved. That’s unfair. I think we all know how the story eventually plays out–it’s the part where we forget who the good guys were supposed to be.

Leave a Reply