The Democratic Party has a faith gap–and if anything it is getting wider. The Gallup Poll has just released data showing a chasm between the political leanings of self-described “very religious” whites, with 62% identifying themselves as Republicans and a scarce 27% identifying as Republicans. At this point, no other demographic skews more heavily toward Republicans than faith oriented whites, and the electoral consequences are unmistakable: it correlates almost evenly with the overwhelmingly Republican preferences of southern whites, who are the most religious whites in America, and further defines why a slew of states with large blocs of evangelical leaning whites are drifting away from Barack Obama, from Ohio to Virginia, to Florida, to Indiana, to Colorado.

The Democratic Party has a faith gap–and if anything it is getting wider. The Gallup Poll has just released data showing a chasm between the political leanings of self-described “very religious” whites, with 62% identifying themselves as Republicans and a scarce 27% identifying as Republicans. At this point, no other demographic skews more heavily toward Republicans than faith oriented whites, and the electoral consequences are unmistakable: it correlates almost evenly with the overwhelmingly Republican preferences of southern whites, who are the most religious whites in America, and further defines why a slew of states with large blocs of evangelical leaning whites are drifting away from Barack Obama, from Ohio to Virginia, to Florida, to Indiana, to Colorado.

There is a mindset in some Democratic circles that religious whites are disproportionately economic conservatives who are natural Tea Party sympathizers. While Gallup did not test specific issues, I have seen a slew of polling data from Alabama–a top two ranked state in football and religiosity–that shows religious whites are often economic populists, distrust corporate elites, don’t mind putting more taxes on those elites, and that surprising shares of them embrace the notion of more government spending on education and, yes, safety nets like Medicaid. They are proud, church-going denizens of the 99 percent, in Occupy Wall Street parlance.

But if the economic lean of religious whites is surprisingly to the left, their stance on social issues leans hard in the other direction. The Public Religion Research Institute recently found that in a country where voters are sharply split on abortion, only 29% of “evangelical” whites favor its legalization, while almost two thirds oppose. Similarly, on same sex marriage, which elite opinion now conclusively favors, and on which the public is split in half, over 80% of white evangelicals oppose legalizing gay marriage.

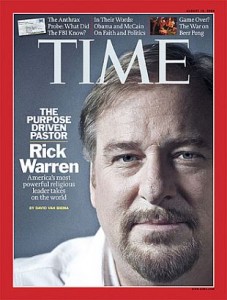

So, in practice, religious whites have voted their sectarian leanings over their economic tendencies. Breaking that pattern was until recently a major Democratic preoccupation. A succession of Democratic thinkers, most notably Jim Wallis, tried to pry the door open by re-casting liberal policies on healthcare, poverty, and educational access as faith-based priorities, grounded in Matthew’s New Testament admonition to advance the interests of the “least of these”. Barack Obama’s keynote address in 2004 sounded an eloquent note that “in the blue states, we worship an awesome God and in the red states, we have some gay friends.” In 2005, Obama’s first high profile speech as a Senator linked his political vision to his faith and its promises of a more seamless community, and during the years of Obama’s rise, there seemed to be a genuine affinity between he and Rick Warren, the avatar of the “purpose driven life” and an evangelical icon.

So, in practice, religious whites have voted their sectarian leanings over their economic tendencies. Breaking that pattern was until recently a major Democratic preoccupation. A succession of Democratic thinkers, most notably Jim Wallis, tried to pry the door open by re-casting liberal policies on healthcare, poverty, and educational access as faith-based priorities, grounded in Matthew’s New Testament admonition to advance the interests of the “least of these”. Barack Obama’s keynote address in 2004 sounded an eloquent note that “in the blue states, we worship an awesome God and in the red states, we have some gay friends.” In 2005, Obama’s first high profile speech as a Senator linked his political vision to his faith and its promises of a more seamless community, and during the years of Obama’s rise, there seemed to be a genuine affinity between he and Rick Warren, the avatar of the “purpose driven life” and an evangelical icon.

In the early months of his presidency, Obama seemed determined to build a beach-head with sectarian minded voters. A 2009 Georgetown speech evoked the Sermon on the Mount, and its haunting parable of a “house built on sand”, as the template for his description of the shaky, unfair foundations of the last decade’s economy. The address shines as one of the most elegant communications in modern presidential history.

Then the ground shifted back. The Georgetown speech was undercut by a blog inspired controversy over whether religious insignia on the stage were deliberately covered while Obama spoke–an absurdity, but a weird premonition that faith was about to become tougher ground for this president. Rick Warren has not been seen at the White House since he prayed at the inaugural, and Obama has not been to Saddleback since the summer of 08. Obama defended his health-care reform in decidedly more prosaic terms–“bending the cost curve”–than spiritual ones, and has not drawn deeply on religious themes since Georgetown. White evangelicals, who afforded Obama a larger share of their votes than they gave John Kerry, have noticeably cooled on Obama and for a while, represented one of the stronger strands of birther sentiment.

Then the ground shifted back. The Georgetown speech was undercut by a blog inspired controversy over whether religious insignia on the stage were deliberately covered while Obama spoke–an absurdity, but a weird premonition that faith was about to become tougher ground for this president. Rick Warren has not been seen at the White House since he prayed at the inaugural, and Obama has not been to Saddleback since the summer of 08. Obama defended his health-care reform in decidedly more prosaic terms–“bending the cost curve”–than spiritual ones, and has not drawn deeply on religious themes since Georgetown. White evangelicals, who afforded Obama a larger share of their votes than they gave John Kerry, have noticeably cooled on Obama and for a while, represented one of the stronger strands of birther sentiment.

To be sure, white evangelicals are caught in the same economic down-draft that has unsettled all manner of voters. Presumably, a recovery that creates jobs and wage growth would win a share of these voters back. But the challenge for Democrats is that the slow, grinding recovery that most Americans think is a recession will still be the state of play a year from now. In that kind of environment, ideology and values will matter, just they did last year, when the GDP was notably stronger, consumer confidence was higher and Democrats still suffered a debacle.

The national Democratic Party is not about to turn to the right on same sex legal equality or the legalization of abortion–indeed, Obama, in declining to endorse gay marriage, is arguably the last high ranking social moderate left in the leadership of his party. But there are still pathways that Democrats and progressives can follow to broaden their appeal to faith oriented voters without alienating their base.

First, liberalism can’t deride faith as the last bastion of bigotry, and it ought to find concrete ways to engage the values of social conservatives. It makes sense to revive the alliance between pro-choice and pro-life Democrats around the urgency of stronger adoption programs. Democratic policymakers, rather than attaching more strings to government alliances with faith based local institutions, ought to welcome religious social centers as allies in attacking urban pathologies. It is also strange that a liberal mobilization like Occupy Wall Street seems so resolutely secular. Every successful social movement of our time has drawn deeply from the social gospel, and a campaign against money changers in the temple of power ought to have a natural affinity for that kind of linkage.

First, liberalism can’t deride faith as the last bastion of bigotry, and it ought to find concrete ways to engage the values of social conservatives. It makes sense to revive the alliance between pro-choice and pro-life Democrats around the urgency of stronger adoption programs. Democratic policymakers, rather than attaching more strings to government alliances with faith based local institutions, ought to welcome religious social centers as allies in attacking urban pathologies. It is also strange that a liberal mobilization like Occupy Wall Street seems so resolutely secular. Every successful social movement of our time has drawn deeply from the social gospel, and a campaign against money changers in the temple of power ought to have a natural affinity for that kind of linkage.

Second, language matters if the goal is to persuade. While the liberal defense of abortion rights shouldn’t retreat from saying that putting prison terms on young women and their doctors isn’t a cost society should bear, with that defense should come an acknowledgment that most abortions reflect irresponsibility and are hardly an assertion of freedom or empowerment: to the contrary, they are usually the furtive act of women who desperately feel they have no other good choices. Similarly, the liberal case for gay marriage shouldn’t always begin and end with claims about rights and social autonomy–instead, it might stress that equalizing marriage laws arguably ties one more class of individuals to the obligations and responsibilities of the marriage contract.

Third, liberals need a better way to address disagreement. The most artful words won’t sway the sentiments of tens of millions of Americans who believe at their core that a fetus is a vulnerable child, or that marriage ought to be defined by churches rather than courts and legislatures. These social moderates and conservatives are Americans too, and an accounting that ridicules their worldview as a bias or their perspective as out-dated is nothing but liberals imitating the old conservative trick of marginalizing their opposition.

Finally, as much as language matters, policies matter more. For example, liberal politicians have been too quick on the draw in rejecting any restriction on abortion access as a right-wing scheme to limit the options of poor women. Solid majorities of Americans favor parental consent laws and trust judges to ferret out the potential for abuse; comparable numbers are deeply opposed to late term abortions and view them as an abuse of the protection the laws give women terminating their pregnancy. Pro-choice advocates would be wise to distinguish between partial birth abortion laws and parental consent statutes and more draconian efforts like the Mississippi personhood amendment.

Sometimes I sense that liberals relate to evangelical voters the way Republicans relate to minorities: that is, happy to improve their voter share from abysmal to respectable, but not if it comes with the price of changing policies or rethinking base-approved rhetoric. The maneuver hasn’t worked for Republicans for the simple reason that people rarely migrate into places where they sense their values aren’t welcome. It won’t work for Democrats either, and they may yet lose a presidential election over it.

Sometimes I sense that liberals relate to evangelical voters the way Republicans relate to minorities: that is, happy to improve their voter share from abysmal to respectable, but not if it comes with the price of changing policies or rethinking base-approved rhetoric. The maneuver hasn’t worked for Republicans for the simple reason that people rarely migrate into places where they sense their values aren’t welcome. It won’t work for Democrats either, and they may yet lose a presidential election over it.

Leave a Reply