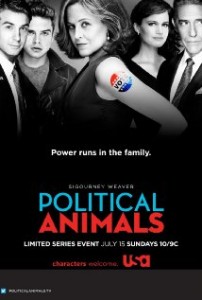

Showtime’s new mini-series “Political Animals” insists that it is not really a knock-off on the saga that is Bill and Hillary Clinton: the resemblance between Sigourney Weaver’s Elaine Barrish and Hillary is merely the surface match between two former First Ladies who endured a presidential sex scandal involving a junior staffer, subsequently launched their own political careers, and lost the Democratic presidential nomination to a smooth, if distant, senator who brings Elaine/Hillary into the Secretary of State’s position. Elaine’s ex, former president Donald “Bud” Hammond, (Ciaran Hinds) just happens to sound, charm, and manipulate like William Jefferson Clinton.

Showtime’s new mini-series “Political Animals” insists that it is not really a knock-off on the saga that is Bill and Hillary Clinton: the resemblance between Sigourney Weaver’s Elaine Barrish and Hillary is merely the surface match between two former First Ladies who endured a presidential sex scandal involving a junior staffer, subsequently launched their own political careers, and lost the Democratic presidential nomination to a smooth, if distant, senator who brings Elaine/Hillary into the Secretary of State’s position. Elaine’s ex, former president Donald “Bud” Hammond, (Ciaran Hinds) just happens to sound, charm, and manipulate like William Jefferson Clinton.

The parallels do break: Elaine Barrish, we learn by episode two, executed the forgiving spouse role only up to a point, divorcing her husband in the aftermath of her defeat in the primaries. And unlike Hillary, Elaine’s loyalties to her new boss are skin deep at best: she is already plotting to take him on in the next campaign. But the severance in the time line does not begin, or even attempt, to mask the obvious: the show is a guilty pleasure window into what the Clintons’ personal and public chaos might look like from the inside, and if the characterizations so far can seem more like an impersonation of the Clintons than an real exploration, it is richly entertaining in the same way the originals are. “Political Animals”, like the real thing it is based on, is a brew of tawdriness, deceit, inspiration, and fortitude, that works in spite of all the reasons it shouldn’t.

Among the reasons it shouldn’t work: the storylines to date–a mini hostage crisis in the Middle East, the Hammonds’ juggling of one son’s engagement party with the other son’s emotional spiral–are pedestrian stuff. The personal sketches reach for their share of clichéd foibles: the young reporter who exposed Bud Hammond’s escapades and has trained her sights on Elaine Barrish has her own penchant for personal turbulence and seems to have boundary issues of her own; the two Hammond children are sons (thankfully, Chelsea remains outside creative license, at least for now) and in predictable modern cinematic fashion, one is tormented, artistically gifted, and gay; the other ferociously protective and resentful of his father’s capriciousness, but if the teasers at the end of the last episode are right, possibly possessed of some of his father’s weaknesses. If cultural stereotypes are your peeve, some of the clichés touch on troubling ground: the Asian woman who is the fiancee of Douglas Hammond is a bulimic perfectionist whose first generation parents are inordinately status conscious; the foreign diplomats are all lecherous or spineless, and there is a weird dearth of African American or Latino characters. This is not the “Good Wife”, whose regular and recurring cast seamlessly integrates every strand of the social rainbow without really trying, and gives each the gift of individuality.

Among the reasons it shouldn’t work: the storylines to date–a mini hostage crisis in the Middle East, the Hammonds’ juggling of one son’s engagement party with the other son’s emotional spiral–are pedestrian stuff. The personal sketches reach for their share of clichéd foibles: the young reporter who exposed Bud Hammond’s escapades and has trained her sights on Elaine Barrish has her own penchant for personal turbulence and seems to have boundary issues of her own; the two Hammond children are sons (thankfully, Chelsea remains outside creative license, at least for now) and in predictable modern cinematic fashion, one is tormented, artistically gifted, and gay; the other ferociously protective and resentful of his father’s capriciousness, but if the teasers at the end of the last episode are right, possibly possessed of some of his father’s weaknesses. If cultural stereotypes are your peeve, some of the clichés touch on troubling ground: the Asian woman who is the fiancee of Douglas Hammond is a bulimic perfectionist whose first generation parents are inordinately status conscious; the foreign diplomats are all lecherous or spineless, and there is a weird dearth of African American or Latino characters. This is not the “Good Wife”, whose regular and recurring cast seamlessly integrates every strand of the social rainbow without really trying, and gives each the gift of individuality.

But if the periphery around the Hammonds is ordinary, recyclable stuff, at the center is a compelling enough rendition of bent characters refusing to break, and in Elaine’s case, making a devil’s bargain in waging the good fight with the same sharp knives that were used to wound her. A fan of the iconic “West Wing” will note that there is not much of that show’s pretense of politics as a noble instrument, not so far: Elaine Barrish is stripped of any explicit political agenda—there are nods to feminism in her concession speech, but it is more an attitude than a platform—and her purpose is rather straightforwardly claiming power from forces that have diminished her.

There is a psychic and public cost to that model, of course, and one suspects that if this show keeps up its promise, we will see it unveiled. Is there a cause that justifies Barrish in risking the wreckage of her party, not to mention’s her adult children’s potential serenity, other than pay-back? Is her estrangement from her husband the break of a woman who has indulged too many lies, or the strategy of a professional who knows that her stock needs re-branding, or the instinct of a survivor proving her own capacities? At the moment, the rooting interest is with Elaine Barrish, but one wonders if the architects of the plot are crafty enough to build doubt and buyer’s remorse into her persona and our view of it as well.

It’s worth asking if this smart, but not deeply creative, show, means for us to notice one other way it channels our reality. The image obsessed, reinvention obsessed Elaine Barrish and Bud Hammond are watchable because they are drawn from the one template that reliably makes for good political drama, real or fictitious: the reimagining of the rush of events and policy clashes into an account of how ambitious human beings master and sometimes deploy their flaws. (their strengths can seem inaccessible to us, the good stuff is how they manage their demons).

That is how Robert Caro has sustained a best-selling franchise on an unpopular leader named Lyndon Johnson for almost 30 years and why David Marannis’ character digs of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama made, and make, money without uncovering any new ground around their presidencies; it is why presidential and political biographies, and autobiographies, still thrive as commercial successes, regardless of their quality, or honesty. How did he/she do it, how did they make it against the odds, what was their trick? Irrespective of our voting preferences, political biography endures partly because it is repurposed as a “how-to” on struggle, or the updated version of making friends and influencing people. These books sell and actually get read when the old political genre of campaign exposes are all but buried (Mark Halperin’s “GameChange” cheated the trend by dishing so much dirt on the Edwards family.)

So, is it just for lack of imagination that public ideals are mostly missing from Showtime’s newest drama? And that the Hammonds are exquisite talents, “political animals” after all, but without any transparent cause? My guess is that Greg Berlanti, the principal behind “Animals”, is being quite deliberate in tapping into the one thread that makes political lives broadly entertaining, and realizing it has not much to do with the ends to which victory is used.

The “West Wing” comparison is instructive again. Some critics maintain that Aaron Sorkin’s brainchild survived and prospered for entirely conventional reasons, mainly the writing genius and its assemblage of on-screen talent. I would add one other variable: in the aftermath of the scandal plagued late nineties and the terror stricken, gray, early part of this century, the notion of an idealistic, imaginative, progressive administration stirred at least the liberal soul. Whatever your politics, Jed Bartlett’s fantasy world had more scarlet than our real one. It is a touch depressing that television’s next venture into presidential drama knows better than to go there again—to the contrary, it gives us devils we know, in a messy unadorned package. Hope and change really has lost its luster.

(Cross-posted, with permission of the author, from OfficialArturDavis.com)

Leave a Reply