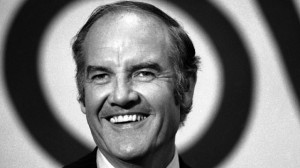

The eulogies for George McGovern, who just died at 90, have taken a predictable form: plaudits from the left for his inspirational effect on a class of aspiring liberal politicos combined with an acknowledgment that he was a singularly ineffective, disastrous candidate whom the same left never needed or cared to rehabilitate. To be sure, the evidence of McGovern’s incompetence and irrelevance is a narrative that Democratic analysts have had their own reasons to spin over the last two generations. It can’t possibly be, so the conventional wisdom goes, that a 49 state loser who spectacularly blundered the selection of a running mate and who is still synonymous with epic loss, was much more than an incidental character in a decade of unusual turbulence. And if McGovern’s legacy is just ineptitude, it is easier to dismiss him as a blip, an anomaly, in the liberal tradition.

The eulogies for George McGovern, who just died at 90, have taken a predictable form: plaudits from the left for his inspirational effect on a class of aspiring liberal politicos combined with an acknowledgment that he was a singularly ineffective, disastrous candidate whom the same left never needed or cared to rehabilitate. To be sure, the evidence of McGovern’s incompetence and irrelevance is a narrative that Democratic analysts have had their own reasons to spin over the last two generations. It can’t possibly be, so the conventional wisdom goes, that a 49 state loser who spectacularly blundered the selection of a running mate and who is still synonymous with epic loss, was much more than an incidental character in a decade of unusual turbulence. And if McGovern’s legacy is just ineptitude, it is easier to dismiss him as a blip, an anomaly, in the liberal tradition.

But the theory of McGovern as a woeful bumbler has always shortchanged two features of the South Dakotan: the first is the novelty of the liberalism that McGovern helped foist on the Democratic Party in the early seventies, and the second is its durability in a party that putatively disowned him while absorbing most of his ideological sensibilities.

But the theory of McGovern as a woeful bumbler has always shortchanged two features of the South Dakotan: the first is the novelty of the liberalism that McGovern helped foist on the Democratic Party in the early seventies, and the second is its durability in a party that putatively disowned him while absorbing most of his ideological sensibilities.

To grasp the novelty, it’s worth noting what post-war liberalism was prior to McGovern’s insurgency: a populist sounding, rhetorically lofty politics that had a transactional, anything but radical reality at its core. Adlai Stevenson was more of a trimmer on school desegregation than Eisenhower era Republicans. John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson pursued conventionally growth oriented economic policies with tax cuts and balanced or near balanced budgets at the centerpiece. The Great Society’s vaunted anti-poverty initiatives were invariably complements to urban political machinery, as Geoffrey Kabaservice documents in his work on the erosion of moderate Republicans, “Rule and Ruin”. Hubert Humphrey disavowed interpretations of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that endorsed mandatory hiring goals for minorities. And on foreign policy, the liberal vision was enamored enough of American power that Robert Kennedy’s announcement of his presidential candidacy styled the campaign as a contest to claim the “moral leadership of the planet”, even while pledging to wind down the conflict in Vietnam.

In other words, the liberal enterprise spent an enormous amount of energy in sustaining an unwieldy coalition of conflicting interests and values, and was not always distinguishable in its words and symbols from at least the establishment wing of its conservative rival. Not many of those vestiges survived McGovern’s trench warfare in the primaries in 1972. In a manner that oddly imitated the Goldwater right’s critique of American society as corrupt and shattered, the McGovernites opened fire on the accommodations that fueled liberalism. In their telling, the whole compromised foundation needed to be razed to the ground: in specific policy terms, tax cuts were discarded in favor of advocating steep corporate tax hikes; gender and racial advancement had to be codified by specific numerical quotas; and the explosion of rights and entitlements from welfare to abortion emerged as official Democratic orthodoxy. The anti-war culture flourished into a full-scale suspicion of American interests and allies abroad.

Calling the McGovern phase a momentary lapse, or some short-lived over-reaction to the Right’s growing hold on Republicans, is a historical rewrite that glosses over the permanent shifts in the Democratic Party in the wake of McGovern’s triumph. The migration of working class whites to the Republican Party, the emergence of a cosmopolitan elite that is small in actual numbers but has a disproportionate megaphone, and the epicenter of racial and sexual identity camps in the Democratic Party are structural features of American politics that seemed inconceivable in the era of Lyndon Johnson and Hubert Humphrey, and they remain fixtures in our electoral life. (Even the foreign policy strains of McGovernism that seem weakest in this election season were vibrant as recent as four years ago, when major elements of the Democratic universe fixated on undoing George Bush’s policies on terror and electronic surveillance, and then Senator Obama’s candidacy might have languished but for its appeal to anti-Iraq War activists.)

To be sure, winning Democratic candidacies, from Jimmy Carter to Bill Clinton to Barack Obama, have seen fit to do their share of strategic rebranding: hence Carter touting his religiosity, and Clinton’s reform of welfare, and Obama’s 2008 emphasis on post-partisanship. But each successive Democrat has shifted rightward only in the context of a left-leaning foundation that McGovern legitimized, and none have cast off the alliance of social or racial minorities and urban, educated elites who have determined Democratic nomination outcomes since 1972. The slow but now almost complete deterioration of social or economic conservatives in Democratic circles means that McGovern’s purge at the Miami convention ended up being prophetic.

It is telling that in most polling, liberalism as a self-identified label remains as weak today, just more than 20 percent of the electorate, as it was when McGovern lost by a landslide. The public’s perception of the liberal worldview is as skeptical now as it was then for largely similar reasons: an association of liberalism with excess and a suspicion that it is more the sum of its constituencies than a coherent, workable vision in its own right. Undoubtedly, McGovern laid those seeds with an inept, ideologically self-absorbed presentation of his ideal American future. But McGovern has been invisible for at least a generation: that the damage lingers suggests that this supposedly catastrophic loser arguably managed the impressive feat of redefining a party in one cycle. Or maybe it’s the seventies that have never really ended.

(Cross-posted, with permission of the author, from OfficialArturDavis.com)

Leave a Reply