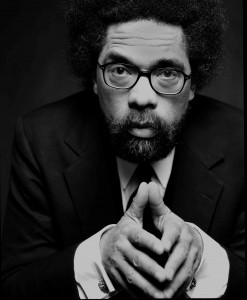

Let me damn Cornel West with some praise that is hardly faint: the Princeton philosopher writes with the lift of poetry even when he is describing something as unsentimental as the nature of American power. He also has the virtue of barbed honesty and has never let the lure of traveling among political princes and celebrities restrain his candor.

Let me damn Cornel West with some praise that is hardly faint: the Princeton philosopher writes with the lift of poetry even when he is describing something as unsentimental as the nature of American power. He also has the virtue of barbed honesty and has never let the lure of traveling among political princes and celebrities restrain his candor.

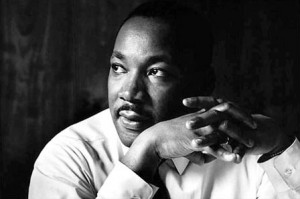

Not surprisingly, those traits–candor and grace–explain why his essay in the New York Times on August 25, 2011, “Dr. King Weeps From His Grave”, has touched nerves in all manner of places.

West’s critique is best captured in one scathing, beautiful sentence: “the recent budget deal is only the latest phase of a 30 year, top-down, one-sided war against the poor and working people in the name of a morally bankrupt policy of deregulating markets, lowering taxes and cutting spending for those already socially neglected and economically abandoned”.

These are arrows aimed at Republicans from Ronald Reagan to John Boehner for the contraction they have forced in the social contract, and at Democrats from Bill Clinton to Barack Obama, who in West’s view have left that contract too thinly defended and have done their own damage by trying too hard to sample conservative rhetoric on deficit reduction and taxes. To put a crescendo on the point, West, an early Obama supporter, calls the “age of Obama” a time that has “fallen tragically short of fulfilling King’s prophetic legacy”.

West is absolutely right about this much: the season of our first African American chief executive has most certainly not reshaped the foundations of our politics in the way that a million plus freezing bodies aligned on the National Mall on January 20, 2009 imagined it would. More Americans self-describe as conservative today, and fewer call themselves liberals, than on the day Obama shattered his glass ceiling, and the net effect is a nation that by roughly two to one leans right rather than left. That is not exactly, in West’s words, a place that sustains a “radical democratic vision.”

West, like most of Obama’s critics on the left, treats the country’s relative conservatism as an essentially irrelevant fact. West never discusses election trends, or the limitations of a check and balance system of government, and more or less ascribes Obama’s failings to either a timidity of will, or a compromised nature borne out of the influence corporate dollars have on politics. Because he leaves the constraints of politics out of the equation, it is impossible to conclude what West suggests a liberal politician like Obama should do in the face of countervailing public majorities.

There is a whiff of the suggestion that a more energetically liberal presidency might have preempted some of the populist politics that the Right has used to thwart Obama. Maybe, and the case can be made that Obama erred in seizing ownership of the bank bailout polices of his predecessor rather than restructuring them to mandate foreclosure relief or more aggressive lending. But it is flatly wrong to suggest that Obama’s declining strength is tied to a backlash at an agenda that has been too slavishly pro-business. To the contrary, every imaginable strand of data suggests that the public entirely and correctly perceives that on healthcare, the regulation of financial markets and carbon emissions, and on the size and scope of government, it is Obama who has offered the most conspicuously liberal agenda. And it is the agenda that a consistent majority of them reject.

I would bet that West would argue that the materialism and selfishness entrenched in American life is to blame. But regardless of the roots of the limits he faces, a President is not a movement leader. He may jar public opinion but he is not free to altogether jettison the mores and values of the country around him. It might distress West that presidents are notorious compromisers–Lincoln’s delayed embrace of emancipation, FDR’s exclusion of domestic workers from Social Security, Truman’s muted reactions to anti-lynching legislation–but trading one priority for another, and calibrating the pace of their advances, is what even superior Presidents do.

West laments that King “never confused substance with symbolism.” But an agenda that is heroically progressive and incapable of achievement does exactly that. The hard, enduring question is the one Reinold Niebuhr alluded to: “the establishment of justice in a sinful world”. The most effective leaders wrestle with how to move the needle in a way that gains more than it concedes, and it is not just the politicians who have to duck and dodge. Dr. King was torn between prioritizing voting rights and economic rights, and the Poor People’s march planned for the summer of 1968 might as easily have been an anti-war mobilization. The point is that the purest of leaders still choose, and sacrifice, and postpone.

If you have read West on contemporary politics or dialed into his tour with Tavis Smiley on poverty, you recognize that he divides the universe in sharp moral terms, between “oligarchs and plutocrats” and “everyday people and ordinary citizens”. But the same Manichaen rhetoric is in vogue on the Right as well: its gap is between “freedom lovers” and a “European style social democracy” that is over-powering us with taxes and red tape. West sees a “catastrophe” in the Right’s mobilization to retake power; the Tea Party is as apocalyptic in its denunciation of the rise of mandates from Washington. West describes the urgency of “life and death confrontations with the powers that be”. The rightwing fringe describes the masses restoring their liberties with Second Amendment firepower.

When the political horizon includes rising stars with the gifts of Cory Booker and Kamala Harris, West cites only two “progressive politicians” worthy of recognition: a Socialist Senator from Vermont and a long-time but nationally unknown county supervisor in Los Angeles. The extremes on the Right are notorious for killing off their own for not being true enough believers, and for elevating the obscure and untested at the expense of seriousness.

What West on the left and his polar opposites on the right feature in common is a disdain for a vision of the public square that does not match theirs. The authenticity is appealing but it is not a “reinvigoration of our public life”, to borrow from West–it is a fracturing of it, and a return to political discourse as a combat zone.

I agree (I think virtually all of us do) that there are any manner of legitimate faults to be found with the way Obama has navigated his 32 months. Yes, West is correct that foreclosure relief should have been prioritized in 2009, that a transportation infrastructure bill should have been advanced rather than delayed three years, and while he doesn’t cite the example, it is maddening that the Administration has filed briefs siding with Republican governors who want to dismantle the core standards in Medicaid and to block the courts from litigants who are trying to stop them.

I agree (I think virtually all of us do) that there are any manner of legitimate faults to be found with the way Obama has navigated his 32 months. Yes, West is correct that foreclosure relief should have been prioritized in 2009, that a transportation infrastructure bill should have been advanced rather than delayed three years, and while he doesn’t cite the example, it is maddening that the Administration has filed briefs siding with Republican governors who want to dismantle the core standards in Medicaid and to block the courts from litigants who are trying to stop them.

But Obama is not wrong to have governed as if a civil politics that does not demonize disagreement beats what he found when he walked through the door. He was right, and not fanciful, in the 2004 keynote, to have imagined Blue states that worship an awesome God and Red states that have tolerance in their veins. I get the impression that West and the Tea Party both think he was deluded. King, I think, would have understood.

Leave a Reply