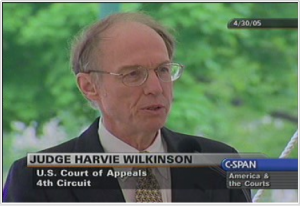

Judge Harvie Wilkinson of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals could easily have been Justice Harvie Wilkinson of the Supreme Court. He was short-listed for vacancies in both 2005 and 2007, and his brand of conservative jurisprudence and judicial restraint bears more than a passing resemblance to John Roberts.

Judge Harvie Wilkinson of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals could easily have been Justice Harvie Wilkinson of the Supreme Court. He was short-listed for vacancies in both 2005 and 2007, and his brand of conservative jurisprudence and judicial restraint bears more than a passing resemblance to John Roberts.

His essay last week in the New York Times is a thoughtful, elegant scolding of both liberals and conservatives who are bent on using the Constitution as the last resort when politics takes too long.

As Wilkinson notes, both the left and right have spent an inordinate amount of time on their own versions of judicial activism—liberals famously so in the context of abortion but increasingly in the context of same sex marriage as well. Liberals favor a robust vision of constitutional privacy over the shifting, ambivalent state of public opinion on both issues. Conservatives, meanwhile, are a week away from urging the court to overturn the Affordable Care Act’s mandate that individuals buy health insurance or risk a fine. If they win, it would be the first time since the thirties that the Court invalidated a major domestic statute.

As Wilkinson notes, both the left and right have spent an inordinate amount of time on their own versions of judicial activism—liberals famously so in the context of abortion but increasingly in the context of same sex marriage as well. Liberals favor a robust vision of constitutional privacy over the shifting, ambivalent state of public opinion on both issues. Conservatives, meanwhile, are a week away from urging the court to overturn the Affordable Care Act’s mandate that individuals buy health insurance or risk a fine. If they win, it would be the first time since the thirties that the Court invalidated a major domestic statute.

Wilkinson’s middle-ground–and that is what it looks like to a public accustomed to putting positions on a left-right grid—is that the mandate ought to be spared in the broader interest of preserving congressional flexibility to regulate a modern economy: to do otherwise, in Wilkinson’s reasoning, risks diminishing the government at a time when other nations are much more able to “flex their economic muscle.” On the other hand, he fears that creating judge-made rights around reproduction or gay marriage weakens our capacity to adjudicate social policy disputes through democratic means.

Wilkinson’s argument rests heavily on the ideal that courts should have the modesty to defer to political processes. His conclusions are certainly a reasonable enough way of looking at the world, and on the issues he cites, a substantial amount of the public would probably end up where he does. There are many skeptics of the cost and effectiveness of the health care law who would still be unsettled if its fate turned on a one vote edge on the Supreme Court. There are countless others who are content to let the debate over gay marriage play out state by state and who would be troubled by the notion that the laws of about 40 states should be reversed by a constitution that is indisputably silent on the subject. Abortion is a closer call, and no issue is more subject to the manipulation of wording and framing; it is notable, though, that Gallup does put the pro-life constituency at its strongest peak in 40 years.

But Wilkinson’s theory seems to have loftier ambitions than finding the sweet spot of public opinion. Measured as a constitutional framework, there is something cursory about Wilkinson’s analysis that stands out in spite of its reasonableness. For one thing, his sensibilities about diluting the government’s regulatory authority sound almost identical to what he laments: a preference for a political vision over a constitutional one. It’s also doubtful that a law that commands barely forty percent support, was the product of a set of unusually messy and blurry deals, and whose mandate provision is its least popular feature, is the best advertisement for the shared values and self-governance that Wilkinson wants to revive.

Wilkinson suggests that “deeply flawed” legislation should be corrected through politics rather than courts, and he is right almost all of the time. But the major constitutional question regarding the mandate–does the government have the power to compel consumers to enter a market even when they don’t want to, and if so, is there any limit on the power beyond practical politics?–is hardly the splitting of hairs Wilkinson suggests (he compares it, in opaque law school fashion, to a decision over whether “the decision not to buy ice cream can be neatly severed from the decision to buy chocolate or vanilla.”) To the contrary, it’s a debate certain to resurface in a time in which liberal activism is focused on making the private sector fit a particular notion of the common good, and a judge who worries about ideological ends over-running the constitution shouldn’t be so sanguine about how the fight ends.

Wilkinson’s case against liberal over-reaching is most sound in the realm of gay marriage, where the political process is working through a rolling state by state referendum—if the result is a mixed bag of laws that reflect deeper socio-cultural splits in the country, that’s an outcome entirely consistent with a preference for democratic change over judicial change. But it is striking that Wilkinson equates a novel and emerging theory of same sex legal equality with a near forty year precedent on abortion. Whatever it’s flawed framework, and even Roe v. Wade’s defenders usually acknowledge that the three trimester/viability regime has been all but wiped out by technology, it is now almost as old as Miranda warnings and just as entrenched as a part of the legal and popular culture. The firestorm from striking Roe down would hardly serve the interests of “tolerance and respect” that Wilkinson admires: much more likely is a fierce eruption over faith, sex, and privacy.

The federal bench would benefit from a hundred more Harvie Wilkinsons—so it’s no insult to say that his model of apolitical constitutionalism exposes the limits of trying to build such a thing. In fact, it’s encouraging to see a top-flight jurist striving to elevate restraint to the top of the judicial value scale—it beats the critical legal theorists and law and economics devotees I recognize from law school. In their identical zeal to change society through the courts, they were prepared to discard a whole lot of democratic process along the way.

(Cross-posted, with permission of the author, at OfficialArturDavis.com)

Leave a Reply