The Arab Spring has led many commentators to ruminate upon the mixed blessings of democracy. As they asked when Hamas won the first free elections in Gaza, or when Hezbollah found itself in government in Lebanon, people today are asking, “Is democracy a good thing if people end up voting for extremists, or if they vote to crush the rights of minorities?” Ross Douthat, reflecting on the increasingly dire situation of Coptic Christians in Egypt, recently posed the question slightly differently, wondering whether the development of modern polities actually requires a kind of forced homogenization that comes at the expense of minorities.

The Arab Spring has led many commentators to ruminate upon the mixed blessings of democracy. As they asked when Hamas won the first free elections in Gaza, or when Hezbollah found itself in government in Lebanon, people today are asking, “Is democracy a good thing if people end up voting for extremists, or if they vote to crush the rights of minorities?” Ross Douthat, reflecting on the increasingly dire situation of Coptic Christians in Egypt, recently posed the question slightly differently, wondering whether the development of modern polities actually requires a kind of forced homogenization that comes at the expense of minorities.

Many if not all readers of this post likely agree that they prefer to live under a system of representative government based on democratic elections. Nevertheless, I wonder how many have taken seriously the structural problem of how democracy encouraging homogenization and its implications for the future. I have to admit it worries me more each day. My inspiration for such worry is not the impending presidential election (which gets more impending all the time as states fall over themselves to push their primaries back into 2011) but rather the approaching Election Day in my own back yard, Philadelphia. This year, as in 2007, the November Mayoral election is a complete afterthought, since it is obvious that Democratic incumbent Michael Nutter will sail to victory over the underfunded and barely noticed Republican challenger (and former Democrat) Karen Brown. The lack of excitement is even greater this time, since in 2007 at least the Democratic primary in May was a close-fought race among several viable candidates, whereas this year Nutter won the Democratic primary handily over token resistance. Then as now, however, commentators have to keep reminding themselves and their readers/listeners that Nutter has not officially been (re-) elected yet, even though there is no doubt.

My point here is not to attack Philadelphia (which I have come to like very much, as only the son of a different but eerily similar gritty post-industrial city) or Michael Nutter, who strikes me as an earnest and honest man. Nor is this a purely partisan complaint—I happen to agree with those Philadelphia Republicans who argue that their leadership is complicit in this situation. The problem is not that the Democrats will win in November. The problem is that, no one even pretends that the election will be competitive. I have seen this same development from the other side, when I lived in the lovely town of Greenville South Carolina, where all the action was in the Republican primary, while the general elections were a foregone conclusion. (That the one-party system was especially entrenched in Chicago, where I lived for the second through seventh years of the Reign of Richard II, goes without saying…)

Across the Delaware, no one expects the New Jersey State Assembly to see more than a handful of competitive races this fall; the House of Representatives is also on its way to being composed of as many one-party districts as possible. In Presidential elections, truly competitive states are a small fraction compared to those that one can predict in advance. What is true on the larger level is true in smaller ways in counties, towns, and boroughs across the country, as voter turnout plummets.

Everywhere, one party rule feeds smugness within the majority, frustration and apathy within among the minority, and a general sterility of political ideas. As a result, citizens lose interest in the electoral process, either seeking to advance their causes in extra-parliamentary protest movements or retreating into sullen silence.

I find that to be sad, and dangerous for the future of democracy.

The transformation of the USA into a collection of one-party units reflects a breakdown of what should be the most important principle of democracy: the need for diversity of views as reflected in competitive elections. If people in Philadelphia, or Greenville, or anywhere, cannot imagine ever voting for a different party, how exactly are they different from voters in states where one-party rule is formally enshrined in law? (The role of Republicans in Philadelphia, for example, with guaranteed sources of patronage and minor power granted in return for permanent minority status, looks an awful lot like that of the non-communist “bloc parties” in East Germany…) Granted, it is also the responsibility of political parties to do what they can to appeal to as many voters as they can, rather than encourage narrow definitions of interest, but the responsibility is mutually reinforcing.

The result of these musings is admittedly paradoxical. Despite current hand wringing about the need for compromise in national policies and complaints about extremism, it is nevertheless true that healthy democratic systems require real competition between parties in elections, and that requires serious disagreement. Without genuine disagreement and serious policy debate, elections become cynical exercises in patronage that only lead to voter apathy and alienation from the system. At the same time, though, healthy systems also require a shared sense of mutual legitimacy that allows both winners and losers to support the result. Losing elections is no fun (a sentiment no doubt echoed by many fellow contributors of the RP), and of course it must have consequences, but neither winners more its losers should view any election as Armageddon. Losing should not lead to charges of illegitimacy, or refusal to work with the winners, but rather to redoubled efforts to do a better job of reaching the electorate in the future. That also requires that the electorate live up to their responsibility to become aware of their options and be willing to challenge their own assumptions.

It can be hard to challenge those assumptions when the dominant party controls patronage. There is also the problem of what I will call, for want of a better term, essentialist politics. If one’s political positions are determined solely or primarily by one’s gender, or one’s ethnic or racial identity, or even by one’s geographic location, that limits the possibilities of political diversity. If political parties set themselves up as the only legitimate standard bearer for a racial, ethnic, or geographic group, (whether we are talking about Shiites in Iraq, African Americans in Philadelphia, residents of the former East Germany, or White Evangelicals in South Carolina) their electoral success may be assured, but at the cost of real democracy. If there is no chance for a member of a group ever changing his/her voting preference, then elections are moot. One could just as easily conduct a census, and leave it at that. This way of thinking is more common than many would like to admit; just take a look at any discussions about drawing electoral districts.

It can be hard to challenge those assumptions when the dominant party controls patronage. There is also the problem of what I will call, for want of a better term, essentialist politics. If one’s political positions are determined solely or primarily by one’s gender, or one’s ethnic or racial identity, or even by one’s geographic location, that limits the possibilities of political diversity. If political parties set themselves up as the only legitimate standard bearer for a racial, ethnic, or geographic group, (whether we are talking about Shiites in Iraq, African Americans in Philadelphia, residents of the former East Germany, or White Evangelicals in South Carolina) their electoral success may be assured, but at the cost of real democracy. If there is no chance for a member of a group ever changing his/her voting preference, then elections are moot. One could just as easily conduct a census, and leave it at that. This way of thinking is more common than many would like to admit; just take a look at any discussions about drawing electoral districts.

As in so many cases, it is easier to identify a problem than to arrive at a solution, and a post like this is at best a first stab at the issue. Be that as it may, the conversation has to begin somewhere. It is worth reflecting upon what a healthy democratic system requires.

- There has to be some amount of shared sentiment (the Founders would have called it “republican virtue”) that accepts the possibility of reasoned disagreement, avoids vilifying opposition per se, and guarantees that losing one election need not mean the loss of power forever. Without such a guarantee, one is left with the situation in many fledgling republics: One man, one vote, one time. Without the basic agreement on the possibility of disagreement, neither winning parties nor their voters can have any incentive to think differently, and minority voters find that their views have no significance at all.

- It also helps to have a developed civil society, as well as apolitical state institutions, to avoid the impression that control of the political levers offers total control to some and total defeat for others.

- It also requires a shared willingness to avoid introducing non-negotiable elements into the political debate. Democratic systems have proven their superiority to totalitarianism precisely where they have shielded much of daily life from political control. The fewer issues included in political debate, the greater the likelihood that there can be a fruitful and respectful disagreement.

- Lastly, it also requires that there be some kind of distinction between campaigning, which requires an emphasis on distinctions, and governing, which requires a search for commonality.

None of these elements can be conjured overnight. But none of them are impossible either, given a willingness on the part of the citizenry to work toward them.

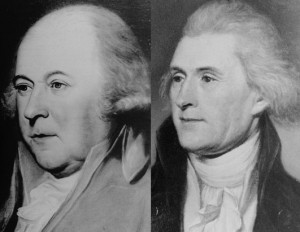

Many historians argue that the most important election in American history was the election of 1800. That hotly contested partisan campaign for president resulted in the defeat of the incumbent Federalist John Adams by the Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson. The peaceful transfer of power from one party to another, accepted by both winner and loser alike, indicated that the American system might just survive. Jefferson famously tried to salve the wounds of the campaign in his Inaugural address, when he declared: “We are all Republicans; we are all Federalists.” The sentiment was appropriate, emphasizing the broadly held common values and ideals of the electorate. What made the election so important, though, was precisely that there were enough differences to make the electorate feel that it had a choice to make. Both the competitive nature of the election and the mutual acceptance of the result were signs of political maturity.

Many historians argue that the most important election in American history was the election of 1800. That hotly contested partisan campaign for president resulted in the defeat of the incumbent Federalist John Adams by the Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson. The peaceful transfer of power from one party to another, accepted by both winner and loser alike, indicated that the American system might just survive. Jefferson famously tried to salve the wounds of the campaign in his Inaugural address, when he declared: “We are all Republicans; we are all Federalists.” The sentiment was appropriate, emphasizing the broadly held common values and ideals of the electorate. What made the election so important, though, was precisely that there were enough differences to make the electorate feel that it had a choice to make. Both the competitive nature of the election and the mutual acceptance of the result were signs of political maturity.

The American political system is well beyond its adolescence, but faces significant challenges in the future. If the American experiment in representative democracy, or any such experiment anywhere, is to survive, citizens need to work toward a system that is just and transparent not only for the winners, but also for the losers of any one election. For neither winning nor losing should be a permanent condition. Each should be merely a stage in an ongoing dialogue in building a just society.

Leave a Reply