By Jeff Smith, on Fri Nov 16, 2012 at 9:15 AM ET

Q: I’m a first-time candidate. After guiding me to victory in my primary, one of my chief strategists asked me to hire his ne’er-do-well son. The son was a campaign volunteer and got along well with everyone, but I turned down the request. I didn’t want to start out my career like that. Did I make the right call, or did I make an enemy for life?

—A Political Neophyte, Kansas City, Mo.

Both.

Q: Does direct mail still work? Is it a good use of money relative to other forms of communication, like TV, radio or knocking doors?

—Initials withheld, New York City

Increasingly, no. There are some places it still works, though. Rural Missouri and St. Louis’ southern suburbs, for instance, are home to large concentrations of seniors, some of whom rarely leave the house, aren’t online except to use email, and for whom snail mail is a highlight of the day. Parts of the outer boroughs in particular also have high concentrations of elderly residents.

Of course, in rural Missouri, television buys are cheap. And moving images (TV ads) are generally more effective/persuasive than mail. So TV is preferable to mail there. But in a legislative race in the outer boroughs, New York City media market TV buys aren’t feasible, so mail is a decent option.

Radio is often a good option for negative ads, since listeners tend to forget the source of the attack and thus don’t hold the attacks against the candidates making them to the same degree they would with a television spot, for instance. But again, this is prohibitively expensive for legislative and City Council candidates in the New York City market. Upstate, it is much more feasible.

Of course, having someone actually talk to voters is always preferable to mail, radio or TV. But some areas are remote and/or difficult to canvass because of the distance between homes. And even in areas that can be canvassed effectively, some campaigns lack volunteers. They may employ paid canvassers as a substitute, but that can be dicey: Those jobs typically pay approximately $10 an hour or even less, and sometimes paid canvassers have more legs than teeth.

My chief opponent in a congressional primary used an oxymoronically named D.C. firm called Grassroots Solutions that hires paid canvassers. They were so stupid that they picked the only day of the entire election cycle when you know who is actually going to vote—Election Day—and spent the morning waving signs outside my office instead of at poll sites talking to voters. So be cautious about hiring anyone who claims they’ll help create “organic” grassroots support.

In sum, yours is a question with which every campaign must grapple. Except in anomalous areas like senior-heavy sections of the outer boroughs, money that once went toward mail will largely be steered toward online advertising in the future. In addition to the Internet’s status as a place where people spend more time than the 15 seconds it takes them to go from the mailbox to the trash can, the Web provides ad buyers information about the number of people who actually see and click on an ad, which mail is unable to do. In a metrics-obsessed Moneyball world, tools that enable campaigns to gather information while assessing the effectiveness of their messaging are increasingly essential.

Read the rest of…

Jeff Smith: Do As I Say — A Political Advice Column

By Jeff Smith, on Wed Oct 10, 2012 at 8:30 AM ET  Q: I recently lost a primary race, largely because a bunch of elected officials I had helped for years ended up screwing me. What’s the best way to get back at them? —Name and location withheld Q: I recently lost a primary race, largely because a bunch of elected officials I had helped for years ended up screwing me. What’s the best way to get back at them? —Name and location withheld

By not spending another minute thinking about getting back at them.

One day in prison, a veteran convict pulled me aside and told me that his brother-in-law had told the feds where his (cocaine) bricks were. “Wow,” I said. “What did you do to him?”

“Thought about the motherf—– for my first three years straight,” he said. “Laid awake every night. Worst three years of my life. But then one day I let it go. Just like that. ’Cause you can’t do time like that. Your boy with the wire…you can’t even think about [the] dude. It’ll make you crazy.” It was the best advice I got in prison; after that, I rarely thought about my ex–best friend.

Your resentment is weighing you down and will reduce the odds of you succeeding in your next endeavor, which would be the best revenge.

By the way, in the future, don’t help others in the hope that they’ll reciprocate. Help people you truly want to see succeed, and then be pleasantly surprised if they reciprocate.

Q: In your last column, some would-be candidate told you he hated asking for money. Instead of providing constructive advice on how to do it, you gave him glib advice about marrying a rich person and other long-shot strategies. How about a better answer? —J.J., New York City

Asking for money can be soul-crushing. But unless we enshrine the public financing of campaigns, it will be a necessary evil. That said, here’s some practical advice about how to make it feel less seamy—and how to succeed at it:

When you first meet a prospective donor, ask for general advice. A few weeks later when an issue arises on which she has expertise, call her and ask for specific advice, but do not ask for money. Then two weeks after that, ask her if she’d be willing to serve in an advisory role on your campaign, a member of “Businesswomen for J.J.” or something. If she agrees, ask for money two weeks later.

Why will this work? First, because now she’s much more invested in you than she would have been had you asked initially. Second, it’s like dating: An attractive woman at a bar gets hit on 10 times a night. A guy can distinguish himself by approaching her without asking her out. When he leaves, she often thinks about the guy who didn’t hit on her more than about the dozen who did.

In other words, after the first few conversations, your prospective donor may be intrigued by the fact that you haven’t asked for money. It’s a fine line to walk, but you can be persistent without being desperate.

Read the rest of…

Jeff Smith: Do As I Say — A Political Advice Column

By Jeff Smith, on Fri Sep 7, 2012 at 8:30 AM ET  Q: I’m 28, a young JD/MBA, triple Ivy, considering a run for office in 5–7 years. Tell me exactly what I should be doing now. —K.S., New York City Q: I’m 28, a young JD/MBA, triple Ivy, considering a run for office in 5–7 years. Tell me exactly what I should be doing now. —K.S., New York City

First and foremost, please don’t ever use the term “triple Ivy” again. On behalf of everyone you will ever meet, thank you.

I’m torn on this one. On one hand, there are some tried-and-true things that will likely help you down the line. Join your local Democratic or Republican club. Attend fundraisers for local candidates—or even better, host them. Knock on doors and phone-bank for your party’s nominees. Those things aren’t foolproof, but if you do them cheerfully for a few cycles, you’re much more likely to earn the support of party insiders.

Though that can work, it wasn’t what I did, and I only advise it to certain types of people. Ultimately it can be just as effective to find a cause you care a lot about and immerse yourself in it. For me it was cofounding a charter school. For you it could be anything, as long as it’s something you’re passionate about. Learn all you can, meet the big guns in that policy space, and better your community in some tangible way. And then, should you decide to run, you’ll have a solid bloc of supporters around your signature issue. It won’t get you the party’s support, but it will brand you as a genuine citizen as committed to the community as to your own political advancement.

Ideally you can focus on the second approach, with just enough of the first to not be ostracized by your local party. But you’ll have to choose your mix. Given your three (!) degrees, my guess is that the first approach is more your style.

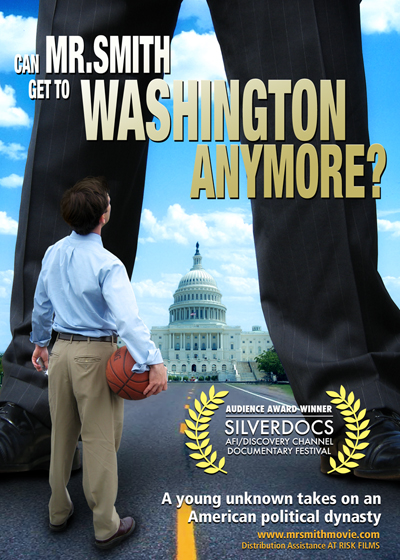

Q: I saw the documentary about you, and now I want to run for office. But I don’t like asking for money. What’s your advice? —Name withheld, via Twitter

Do one of the following: 1) Start a business and get rich so you can self-fund; 2) Marry a rich girl/guy (more options if you’re here in New York than in most states); 3) Befriend a billionaire who will instinctively know to fund an independent expenditure on your behalf without your asking; 4) Run for town council or another office with an electorate under 10,000 people; or 5) Ditch your political dreams.

Q: Do yard signs matter? —S.S., San Diego

In the movie Singles (1992), Bridget Fonda’s character asks her boyfriend (played by Matt Dillon), whose taste tends toward voluptuous women, if her breasts are too small. “Sometimes,” he replies.

And so it is with yard signs. In a presidential election they don’t matter. About 95 percent of the country has already made up its mind, and those who haven’t have ready access to nearly unlimited information about the two candidates.

In low-information down-ballot elections, especially primaries, signs matter, especially for little-known underdog candidates who are desperately trying to raise their visibility and to show the support of people who are well respected in their neighborhoods. Signs can also help candidates keep their supporters psychologically invested in the campaign.

Q: I have a friend in politics who’s headed to prison, and he wants to hire a prison consultant. The one he contacted wanted $7,500 up front. Is it worth it? —C.M., New York City

I’d do it for half that. Oh, and tell him not to eat the Snickers. That one’s free.

Read the rest of…

Jeff Smith’s Political Advice Column: Do As I Say

By Jeff Smith, on Wed Aug 8, 2012 at 8:30 AM ET Today, we proudly present a new feature at The Recovering Politician. Jeff Smith, one of our most popular contributing RPs will be answering YOUR political advice questions here and at City & State, a very popular Web site that focuses on New York politics.

Please send in your questions for Jeff to staff@TheRecoveringPolitican.com, and Jeff might answer them in subsequent columns.

My name is Jeff Smith, and I’m a recovering politician. Oh, I still love politics, and I follow it as closely as ever. But I no longer have a political future; the U.S. Attorney in Missouri’s Eastern District saw to that. My name is Jeff Smith, and I’m a recovering politician. Oh, I still love politics, and I follow it as closely as ever. But I no longer have a political future; the U.S. Attorney in Missouri’s Eastern District saw to that.

After a 2004 congressional bid in which, as a 29-year-old nobody, I lost narrowly to the scion of Missouri’s leading political dynasty, I figured I was done with politics. But thanks largely to a documentary film about our first campaign I got sucked back in, winning a State Senate seat two years later. I adored the Senate—loved crafting policy, loved helping people, loved the camaraderie with my colleagues.

Then, through an uncanny series of events involving a lie, a car bombing (in which I had no part) and my best friend’s wiretap, I spent 2010 in federal prison.

Along the way I learned about politics, policymaking and people; about friendship, temptation and betrayal. Mine is a hard-won perspective, but one I’m honored to have the opportunity to share with City & State’s readers.

One of the hardest things in politics is knowing whom to trust. That makes discretion critical, since asking a friend for advice can be akin to calling a press conference and broadcasting it.

This column aspires to be the confidant you can trust for an unvarnished opinion: a “Dear Abby” for politicos, if you will. I look forward to answering questions about all things political, and helping readers gain their wisdom more easily (and anonymously) than I did.

I’m running for office, and though I have some volunteers, most come in once, then disappear. I asked my campaign manager why and he said they were all flaky. Do you have any advice?

S.E., Webster Groves, Mo.

Dear S.E.:

First, fire your manager; he sounds flaky. Second, sit down with volunteers when they come in. Ask them why they’re volunteering and what their dream campaign job is. Then—unless their answer involves holding a press conference or sleeping with the candidate—give them a chance to do it. They may have to hit 100 doors before they get to draft a press release, design a mail piece or storyboard a TV ad, but they’ll have a reason other than cold pizza to stay engaged.

Finally, the heart of the problem: Your campaign is no fun. Make your campaign a social event. You’re the candidate; you set the tone. If you’re having fun, they will too—and you’ll attract more fun people. I used to bet my interns/volunteers on anything: One-on-one basketball, who could recruit more supporters while canvassing, which one of them could get somebody’s digits at an event. It’s possible to have a blast and be deadly serious about getting votes at the same time.

I’m a legislator who screwed up. I promised a school superintendent in my district that I’d vote against new charter schools, then told the charter-school advocates that I’d support their bill, which would allow for charter-school expansion. If I seek higher office, the public-school types and teachers’ union could get me primary votes, but the charter-school lobby donates pretty heavy. What should I do?

W.C., St. Louis

Dear W.C.:

In the future, only make promises you can keep. But since it’s too late this time, here’s what you should do. Since you appear to be agnostic about which is the best policy, call some informed constituents without a stake in the matter to feel them out. If there’s any consensus, vote that way. Then, if you must break your word, you have the one semi-acceptable excuse: “I’m sorry. I heard from my constituents and thought hard, and I decided to vote ‘No.’ This was a good lesson; next time I won’t give my word until I understand the issue better.” And tell them well before the vote so they don’t count you as a “Yes.”

Last, before running for higher office, get your views straight so you’re never again making policy calls based purely on personal political considerations. It screams “hack,” and it’s why people distrust pols.

I’m an elected official who recently found out that my female chief of staff had sex with three male interns. I’m not sure whether to talk to her or high-five them—she’s pretty hot. But seriously, should I say anything to her?

D.A., Miami

Dear D.A.:

If your male chief of staff had banged your last three female interns, would you say anything to him? (Hint: Any answer that includes the phrase “high-five” is incorrect.)

Read the rest of…

Jeff Smith: Do as I Say — A Political Advice Column

|

The Award-Winning Documentary about Jeff’s Early Career (2006):

The Recent New Republic Article About Jeff (2011):

|

|

|

Follow Jeff Smith: